Whether it was the money, the climate, or the awkward spot on the tennis calendar, the $150,000 Alan King Classic at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas was a goldmine for underdogs. Top seeds Stan Smith and Rod Laver lost their opening matches. Numbers three and four, Ken Rosewall and John Newcombe, fell in the second round. Only two top-ten seeds reached the quarter-finals, and one of them–Cliff Drysdale–went no further.

The desert heat–often touching 95 degrees–favored the biggest hitters in the game. Laver lost to six-foot, four-inch Dick Crealy, and Newcombe went out to another Australian, Colin Dibley, who once cracked a 148 mile-per-hour serve. Roscoe Tanner, owner of the liveliest arm among the Americans, ousted both Rosewall and Drysdale.

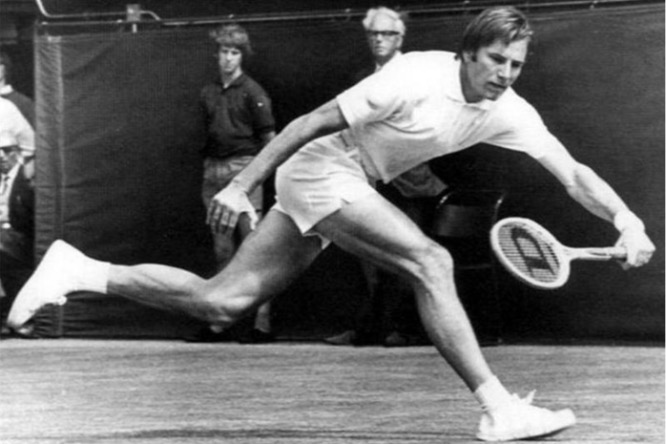

The tournament, along with its record-setting $30,000 prize, seemed to belong to Arthur Ashe. The last seed standing, he was coming off a near-miss to Smith at the previous week’s WCT Finals. Having learned the game in Virginia, he had no problems with a blistering sun. His serve could be every bit as unhittable as Tanner’s.

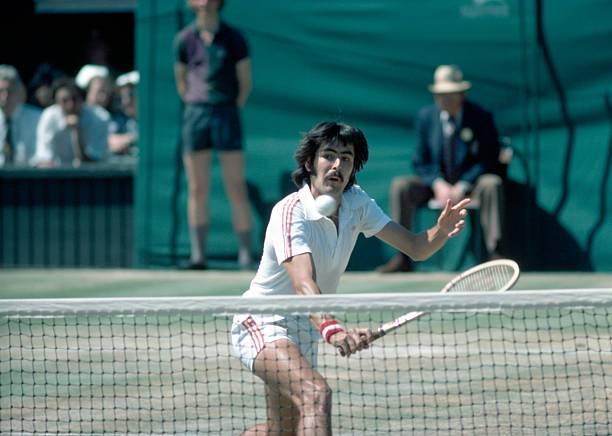

Just when the resident gamblers thought they had figured out the pattern of the Alan King Classic, Brian Gottfried screwed it all up. A curly-haired 21-year-old counterpuncher from Trinity University in Texas, he moved quietly through the draw, beating Clark Graebner, Charlie Pasarell, and Dibley to reach the semis. He straight-setted another veteran, Cliff Richey, for a place in the final.

What Gottfried lacked in power and pizzazz, he made up for in other ways. His second serve was only slightly weaker than his first. He executed well at the net, even if he didn’t come in behind many serves. Until recently, he had been the third-ranked player on the Trinity squad; he was already gaining a reputation as one of the circuit’s hardest workers.

Ashe liked to joke that after Gottfried skipped practice for his wedding, he doubled his workout the next day to make up for it.

On May 20th, it wasn’t just hot, it was windy. The finalists coped with gusts up to 25 miles per hour. Ashe was never known for playing with a wide margin of error, and it cost him. The favorite double-faulted twice on break point in the second set.

Across the net, Gottfried was unfazed. He broke serve twice in the first set and three times in the second. “I just decided to keep banging the ball hard against his serve… and it worked out,” said the new champion, who won the match, 6-1, 6-3.

It was, by far, the biggest title of Gottfried’s young career. He had won the Johannesburg WCT event, another upset-ridden week, but that championship didn’t quite count: He won the final by walkover when Jaime Fillol was ill. Gottfried won the Vegas doubles, too, for a one-week take of $35,000, more than doubling his career earnings. He had turned pro just nine months earlier.

Arthur, as usual, was eloquent in defeat. “He was hitting out there like there was no wind,” he said. “I wasn’t.”

* * *

Also this week:

- You didn’t think they would hold a tournament in Las Vegas without an appearance by the king of the hustlers, did you? Bobby Riggs took part in a one-day “Hall of Fame” doubles tournament played in conjunction with the Alan King Classic. With partner Gardnar Mulloy, Riggs beat Don Budge and Dick Savitt in the opening round, but lost the one-set final to Richard González and Frank Parker, 6-2. “What did you expect?” Bobby chirped. “Those guys had 12 years on us, 103 to 115.”

- Evonne Goolagong picked up her fifth title of the year at the Mercedes Benz Open in Lee-on-the-Solent, England. It was a minor event against primarily British competition. The rewards were even less distinguished: The day before Gottfried collected his $35,000, Goolagong received her winner’s check for $312.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: