Boy, that escalated quickly.

Two days after the International Lawn Tennis Federation (ILTF) upheld the ban on Yugoslavia’s Niki Pilić, a group of nearly 100 top professionals made it clear that if Pilić couldn’t play Wimbledon, neither would they.

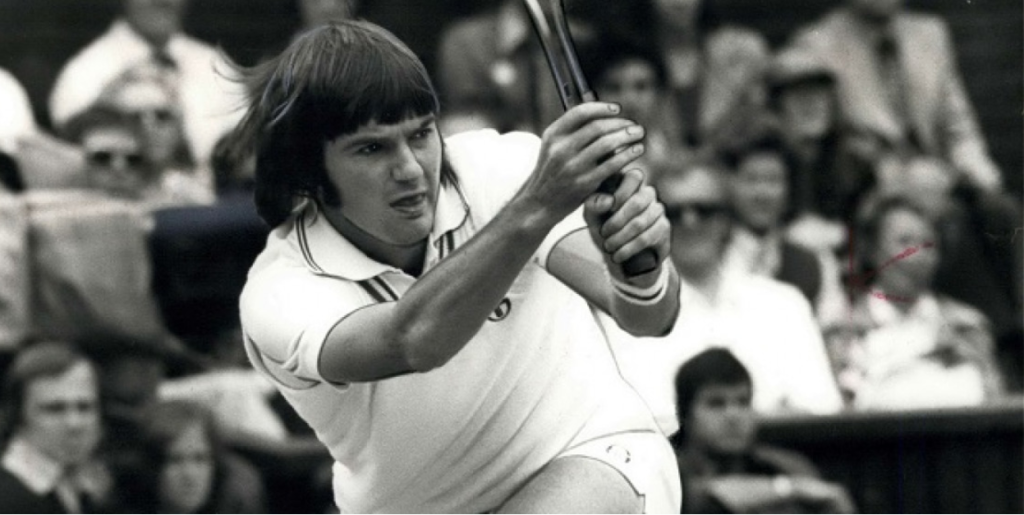

The voice of the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) was Cliff Drysdale, a veteran South African player who served as the body’s president. Drysdale represented almost every notable player in the game: Rod Laver, Arthur Ashe, Ken Rosewall, Stan Smith, and more. Just a few pros stood outside the ATP’s ranks, like Jimmy Connors. Both Jimbo and his manager, Bill Riordan, had decidedly independent streaks. Some Eastern Europeans answered only to their national federations, and a handful of youngsters–such as Björn Borg–had yet to sign up. That was it.

Drysdale said that the suspension was a mistake, and that the ILTF couldn’t prove otherwise. The Yugoslavs claimed that Pilić had “refused” to play a recent Davis Cup tie. The player said he had never committed to suiting up for Yugoslavia. In the union’s view, there was no evidence that Pilić ever promised anything, and that was that. The South African claimed to be optimistic that upcoming meetings between the two organizations would result in a solution. But the general readiness to forgo the biggest event on the tennis calendar suggested otherwise.

The next few weeks would be the first real test of the ATP’s strength. The players’ union had been formed only nine months earlier, during the 1972 US Open. Two powerful factions–the ILTF and Lamar Hunt’s World Championship Tennis (WCT)–had just reached a peace pact of their own, divvying up the calendar and ending the prohibitions on some types of players at certain events. The players needed to be at the negotiating table, too. They were, as Ashe put it, “tired of being stepped on by two elephants.”

Ashe took an officer role alongside Drysdale. But the force behind the union was former player and promoter Jack Kramer. Kramer had won Wimbledon in 1947 by perfecting the serve-and-volley game, then gone on to dominate the professional ranks. He quickly moved into management, recruiting amateur stars and running the pro tours. Traditionalists demonized him for soiling the game with dollar signs, but Big Jake simply wanted the players to get their share of the action. There was lots of money in “amateur” tennis.

Kramer liked the tell a story about getting called into the office of one of the USLTA’s chief administrators. The man had heard that Jack–still an amateur in those days–was making a healthy living collecting “expenses” from tournaments beyond the amount necessary to keep him fed and sheltered on the road. It was common practice, but everyone was expected to go along with the charade of playing wholly for the fun of it. Instead, Kramer told the man: Yes, absolutely, he was earning more than he spent. He had a wife and sons to feed. In my situation, he asked, wouldn’t you do the same?

The federation bigwig sent Kramer on his way. The matter was dropped.

From the mid-1950s onward, Jack fought for Open tennis, and he made at least a handful of his fellow players rich. He saw far into the future, predicting a sort of Grand Prix tournament schedule a decade before it came to pass. His pros played tiebreaks long before the majors did. Most of all, he realized that the health of the sport depended on the players–a truism now, but a radical notion at the time. Long before 1973, he knew that the athletes needed their own organization. He told Billie Jean King that the women ought to have one, too.

Kramer’s story is important because his motivations were so often misconstrued. Tennis had given him a comfortable life, so detractors saw him as a money-grubber. His involvement in the Wimbledon boycott caused some–especially in Britain–to accuse him to trying to destroy the game entirely. History has cast him as a villain for different reasons: His support for unequal men’s and women’s prize money inadvertently triggered the formation of an independent women’s tour. But for all of his faults, Kramer pushed for a vision that was awfully close to what professional tennis ultimately became.

Ultimately, Big Jake would play only a supporting role in the drama of the 1973 Wimbledon Championships. While he had a front row seat, the decision–and the sacrifice–of a boycott was up to the players themselves. The ATP’s stated mission was to “unite, promote and protect” the interests of its members. Pilić was one of them, and it sure felt like he was being trod upon by an elephant. The ILTF didn’t recognize the resolve–or the power–of their new adversary. That would soon change.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: