In 1973, tennis was still not an Olympic sport. It hadn’t featured as a full medal discipline since 1924, and its appearance as a demonstration sport in 1968 had yet to bear fruit. The original break in the 1920s was due to differing definitions of professionalism. By the early 1970s, the sport and the Games were further apart than ever. Stars could rake in sums of money that watered the eyes of promoters and offended the amateur sensibilities of the Olympic movement.

Tennis, however, had long been a staple at the Maccabiah Games, the quadrennial “Jewish Olympics.” Dick Savitt, the 1951 Wimbledon champion from New Jersey, won medals at the event. Tom Okker of the Netherlands starred at the Maccabiah in 1965, three years before reaching the final of the first US Open. And in 1969, Julie Heldman made the trip to Israel and ran the table, winning the singles, doubles, and mixed.

The Open era didn’t do Maccabiah tennis any favors. There was no money involved, and a medal carried little prestige within the tennis world. The schedule was awkward, too. It wasn’t a typical Monday-to-Sunday tournament, so participation would effectively lop two weeks off of a player’s schedule. Tel Aviv wasn’t exactly geographically convenient to the circuit, either.

As a result, the Maccabiah went the way of many long-standing amateur events. It became, more and more, a de facto junior competition. Okker had been 21 when he waltzed through the field, and Heldman did so well because she had more experience than the rest of the women combined. The stars of the 1973 Games would be the youngest yet.

No one at the Ninth Maccabiah, regardless of age, could ignore the fact that this one was different. The opening ceremonies honored the eleven Israeli athletes killed by Palestinian terrorists at the Munich Olympics just ten months earlier. Security at Ramat Gan Stadium was tight.

Tensions ran high, too. Two Dutch athletes had withdrawn from the Munich Games out of respect for the Israeli victims; they were invited to participate in Tel Aviv, despite not being Jewish. They would have full status as competitors, except that they couldn’t win medals. At the event, however, they–along with a few other non-Jewish athletes–were sidelined due to last-minute disputes. An American coach protested just five minutes before one race was set to begin. His complaint: It would be ridiculous if a guest won the race and a second-place finisher were awarded the gold medal.

Or as he put it in the heat of the moment: “If somebody doesn’t get that Norwegian off the track, I’m going to punch someone.”

Another American, a doctor traveling with the United States delegation, actually did punch someone. He roundhoused an official over a decision in the boxing event.

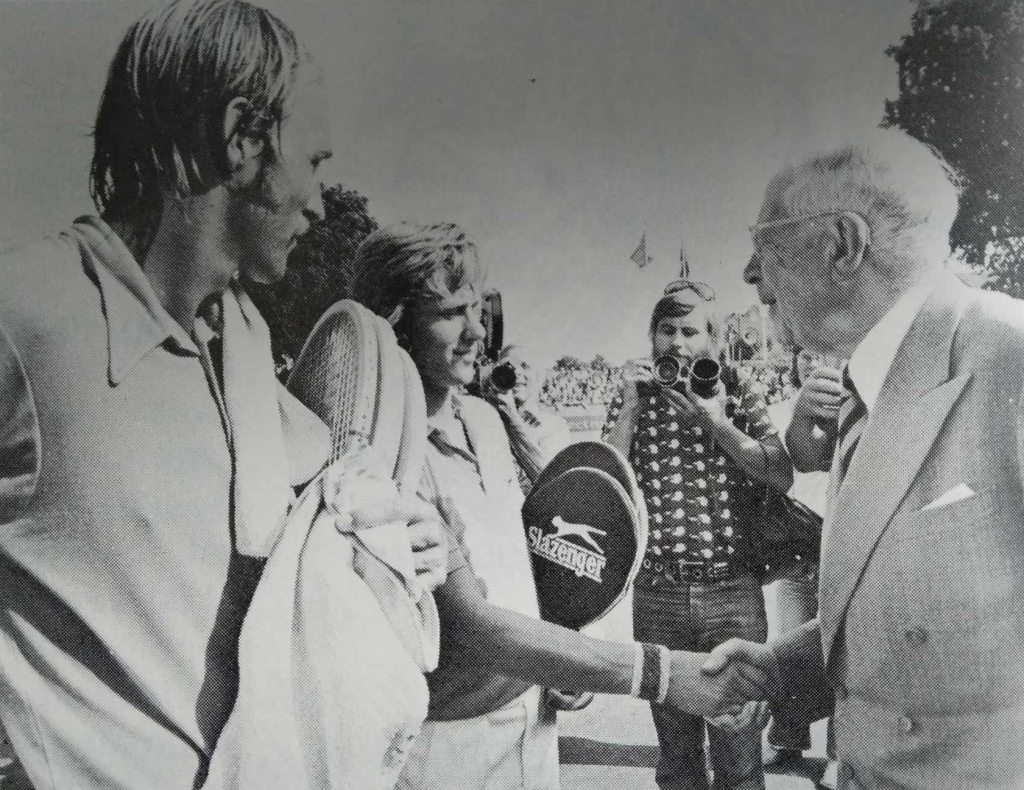

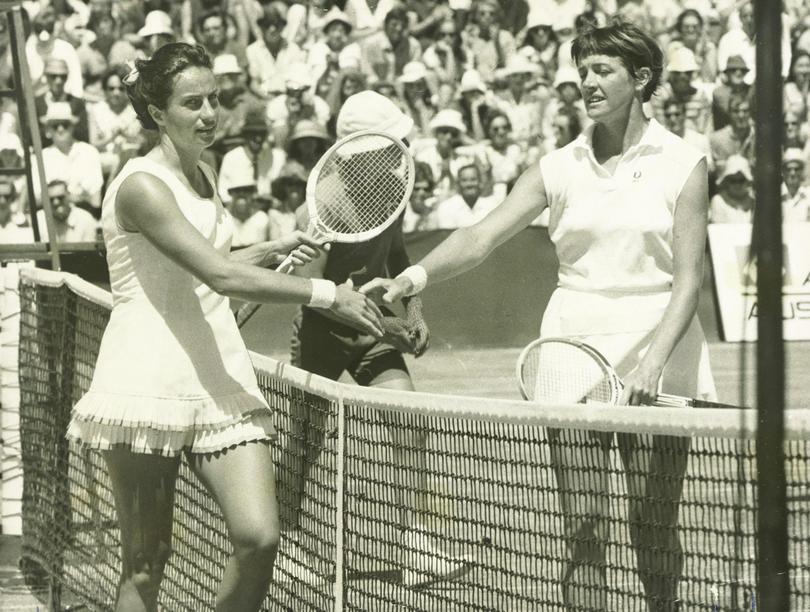

The tennis competitions progressed unaffected. The standouts came from South Africa: 17-year-old Ilana Kloss in the women’s tournaments and 18-year-old David Schneider in the men’s. Neither had much international experience, and both were several years away from their peaks. Still, on July 16th, Kloss won the singles gold medal, beating Janet Haas of Florida, 6-1, 6-3.* It was her second triumph in two days. She had picked up the doubles title the day before, and she would leave Tel Aviv with three gold medals, including the mixed doubles prize with Schneider.

* Haas was no slouch, and she deserves more than this footnote. She captained the University of Miami tennis team in 1972 and 1973. The first woman tennis player awarded an athletic scholarship by the school, she now has a place in Miami’s Sports Hall of Fame.

For the time being, the Maccabiah was the closest a tennis player could get to the Olympics. The International Olympic Committee remained behind the times, failing to grapple with the questions of professionalism that continued to roil tennis. The Jewish Olympics offered an occasional reminder that the whole debate was dumb. Somehow, the few hundred dollars in prize money amassed by Kloss and Schneider in their young careers did not irreparably soil the Games.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: