Last year, Madison Keys missed the Australian Open with a shoulder injury. She ended up playing barely half the season, missing more time after tearing a hamstring at Wimbledon. She still won enough matches to head to Melbourne as the 19th seed at this year’s first major.

She’s better than that.

In one sense, I’m just stating the obvious: She beat Jessica Pegula for the title in Adelaide on Saturday and moved up to 14th on the WTA computer. Beyond that, anyone who can hold on to a spot in the top 20 despite missing so many events is probably better than their ranking. Elo agrees, rating Keys ninth among women, a modest 33 points behind fifth-place Elena Rybakina.

Even more striking is the way the American won the Adelaide championship. She served as well as she has in years, indicating that the shoulder is fully healed. She played extremely aggressively, a style that she has never shied away from, but that she sometimes struggles to maintain. Finally, Keys did all that while posting excellent return numbers. The 29-year-old is a two-time semi-finalist at the Australian Open, and if she keeps this up, she could easily make it three.

The serve is back

When everything clicks, no one on tour–with the possible exception of Rybakina or Aryna Sabalenka–makes serving look so easy. Keys doesn’t just slam flat serves down the tee: She adds a bit of side spin, so her inch-perfect deliveries look like they’re sailing slightly wide until after they cross the net. Then she employs the same spin to send wide serves even wider. When she misses, she can fall back on some of the heaviest topspin seconds in the women’s game.

Whether the shoulder was still shaky or the hamstring compromised her motion, the American struggled to maximize her serve as late as last year’s US Open. In her third-round loss to Elise Mertens, her average first-serve speed was just under 99 miles per hour. Out of nearly 100 grand slam matches for which I have serve speed data, it was only the second time–the other was 2017 Roland Garros–that she hit firsts so slowly.

Today in her Melbourne opener against Ann Li, her average first serve was 109 miles per hour. That’s the fastest I have on record for her since 2015.

I don’t have serve speeds for Keys’s victories last week in Adelaide, but the results hint at numbers well into triple digits. In the final against Pegula, she hit 10 aces, good for 13% of her serve points. Facing Liudmila Samsonova in the semis, she smacked 12 aces–17% of serve points. In a short quarter-final against Daria Kasatkina, she tallied 11 aces, an eye-popping 21% of serve points. It was only the fourth time in the 2020s that Keys topped the 20% mark and the only time in her career she managed it against a top-ten opponent.

Adelaide marked the first time since 2019 that the American aced at least 10% of her service points in three consecutive matches. She hadn’t done so at a single event since 2016.

Aces are great in themselves, but the stat is particularly useful for representing the serve’s effect on even more points. Yes, Keys won 13% of her serve points against Pegula with aces, but 41% didn’t come back. That’s another sign of a revival: In dozens of Match Charting Project-logged matches, it’s the first time she’s topped 40% in that category since the Australian Open in 2022–her most recent semi-final run Down Under.

The American mitigated her shoulder woes last year by starting points more conservatively. She wasn’t as deadly with her first serve, but she landed more of them. Among the WTA top 50, only Elina Avanesyan and Yulia Putintseva missed fewer first serves. If Adelaide is any indication, it’s back to business as usual, taking a few more risks and wreaking absolute first-serve devastation:

Span SPW 1stIn 1st W% 2nd W% Adelaide 65.4% 63.4% 71.6% 54.8% 2024 60.6% 68.2% 66.7% 47.4%

It’s not an apples-to-apples comparison, because the 2024 line contains plenty of clay-court matches, including two against Iga Swiatek. But the difference is sufficient to tell the story anyway. 60.6% of serve points won was good for 8th-best on tour last year. 65.4%, on the other hand, is almost two percentage points better than anyone posted on hard courts. The 71.6% first-serve win rate would have put her in the top five, and no one came close to winning 54.8% of their second serves.

I don’t want to put too much emphasis on a single tournament–everybody looks good if you turn the microscope on a great week. But it’s worth offering one more tidbit in Keys’s favor. She posted those numbers against extremely strong opposition. Her five victims in Adelaide were ranked 16th, 17th, 9th, 26th, and 7th, respectively. That’s a tougher schedule that any player faces over the course of an entire season. If Madison does reached the Melbourne semis, it’ll be an easier path than she faced to collect the trophy in Adelaide.

Swinging freely

Keys has improved her return game over the years, and she’s gotten more comfortable playing long rallies. One of the more surprising numbers on her stat sheet is that she has a better winning percentage on clay than on hard courts.

Still, she’s an aggressor at heart. Her serve isn’t the only shot she can hit as hard as anyone, nor is it the only weapon she can land on the line. Generally speaking, the more aggressive she is, the better her results. The shoulder and hamstring injuries forced her to play more conservatively. That is now over.

In less than an hour on court with Kasatkina, she crushed, by one count, 38 winners. Facing Pegula on Saturday, she tallied 40. I have winners and unforced errors for about one-quarter of her career matches, and the Adelaide final was the first time she cracked 40 winners since 2019. It wasn’t uncontrolled either. The opposite side of the ledger was a respectable 27 unforced errors, good for a ratio of 1.5. Even in her Auckland loss to Clara Tauson the previous week, she recorded 38 winners against 30 unforced, a ratio that would win most WTA matches.

The best indicators of the American’s renewed attack are the various metrics for aggression. By Rally Aggression Score–a measure of how often a player ends points for good or ill after the return of serve–she rated +147. (Average is 0, and almost all players fall between -100 and 100.) Return Aggression Score–the same idea, but strictly for returns of serve–put her at +137. Her career averages are around +100, but in 2024, she fell below +60 in both.

The last time that Keys reached +137 or higher by both measures was the 2019 Cincinnati quarter-final, when she beat Venus Williams en route to the title.

We keep finding things that Keys has done for the first time since 2019. They almost all go back to that week in Cincinnati. (Coincidentally, she straight-setted Kasatkina there, too.) With the possible exception of her 2017 US Open final run, the Cincinnati effort was the best of her career. She has found that form again.

Keys to the match

One difference between 2019 Cincinnati and 2025 Adelaide: The American returned a whole lot better last week. She won 48.1% of return points in Adelaide, compared to 43.7% in Cinci.

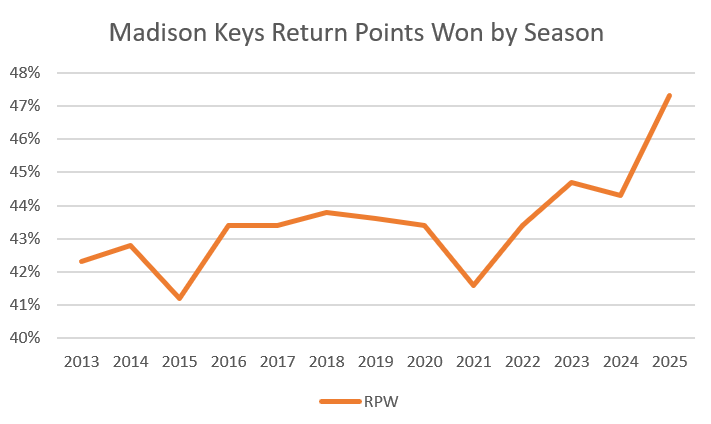

It’s rare for players to substantially improve their return game once they arrive on tour. The rest of the tour learns how to beat you, the opposition gets stronger, and age slows you down. Yet Keys, in her late 20s, has gotten better:

While the 2025 data point probably won’t stick above 47%, the 2023 and 2024 results demonstrate the trend. Last year, Keys’s 44% mark was better than half of the top 50, a strong showing for a serve-first player. Return points are an extreme case of tennis’s small margins. By top-50 standards, 43% of return points is weak, 44% is adequate, and 45% is strong.

47%–the American’s success rate in Auckland and Adelaide–is beyond elite. Only two players–Coco Gauff and Marketa Vondrousova–did better than that on hard courts last year.

It will take some time before we know whether Adelaide was an outlier or a harbinger of a resurrected career. Keys’s 2025 season will surely fall somewhere in the middle, at least if she remains healthy. There are certainly reasons for optimism. For the most part, she’s done all of this before, serving and attacking her way into the top ten as far back as 2016, and returning better in the last two years. If those two halves come together, we won’t see a (19) next to her name again for a long time.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: