Here’s an impressive stat for you: Last week in Austin, champion Yuan Yue won more than half of the return points she played. In fact, had she picked up just one more point against Wang Yafan’s serve in the quarter-finals, she would have won at least 50% of return points in each of the five matches she played.

This isn’t earth-shaking stuff: There are about a dozen tournaments every year where the champion wins more than the 51% of return points than Yuan did in Texas. Iga Swiatek won 56% at the French; Aryna Sabalenka cleared 52% in Australia. Lauren Davis won 53% in Hobart last year. The average single-match loser on the WTA tour loses about half of their return points, so it’s not far-fetched that a titlist would rack up these numbers for five or six days running.

Still, this is Yuan Yue we’re talking about. Not only was the 25-year-old Chinese woman a longshot to win the title–it was her first on tour–she has hardly established a reputation as a steady returner. A dangerous one, perhaps: In last year’s Seoul final against Jessica Pegula, Yuan turned one out of six of the American’s deliveries into a return winner or forced error. But the overall results weren’t so impressive, as she won fewer than 40% of return points in the match. For all of those big swings, there were lots of swings and misses. Out of five matches in an otherwise encouraging week in Seoul, she won more than 46% of return points only once.

The game Yuan brought to Austin was something different. Like San Diego champ Katie Boulter, she took fewer risks than usual, trusting that she could win points a shot or two later. Facing Pegula, and in another losing effort to Emma Navarro in the Hobart semi-finals, Yuan’s average return point lasted four strokes. Against Wang Yafan on Friday, return points took six. Yuan hit just three return winners in that match; in the final against Wang Xiyu, she didn’t hit any. Presumably she’s ok with that.

The magnitude of Yuan’s achievement isn’t quite the same as Boulter’s: The Brit beat five opponents ranked in the top 40, and Yuan didn’t face anyone in the top 60. Yet the week marks a major step forward. The 25-year-old cracked the official top 50, and Elo now rates her as the second-best Chinese woman on tour. If she continues to put returns in play the way she did in Austin, she could climb even higher.

One more ball

Returns in play are good, but they come at a cost. Do you aim to stay in as many points as possible, accepting that a lot of your returns will be weak, or do you swing big, piling up errors in exchange for a handful of return winners and better odds when your returns find the court?

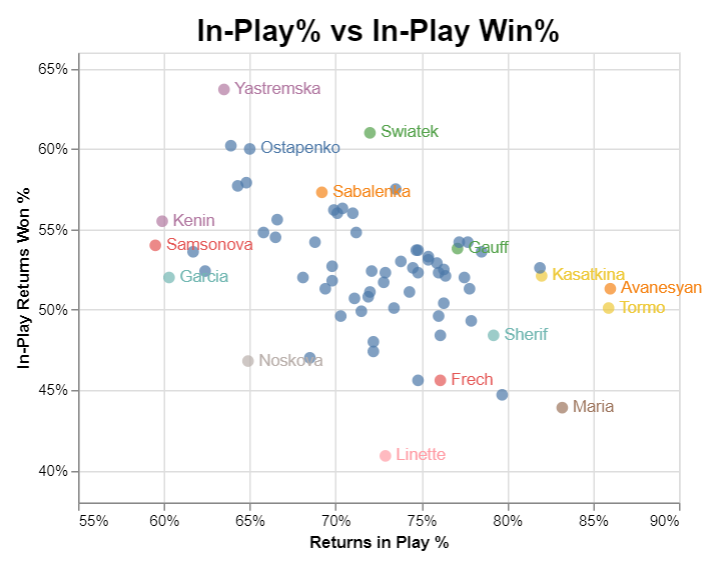

While the pros and cons are different for every player, no one escapes the tradeoff. Even across players, there is a persistent negative correlation between returns in play and in-play returns won. If you make more, you win fewer of them. The following plot shows those two numbers for every woman with at least five matches in the Match Charting Project dataset from the last 52 weeks:

The best place to be is the upper-right corner, with a lot of returns in play and a lot of those points won. Except… that sector is mostly empty. The women who get the most serves back–Kasatkina, Avanesyan, Sorribes Tormo–win those points at an average rate. Even that success rate is boosted a bit by the slower courts where those players tend to succeed. By contrast, the players who win the most in-play return points–Swiatek, Ostapenko, Yastremska–achieve that by missing a lot, or by being an all-time great. Even Swiatek doesn’t put an above-average number of returns in play.

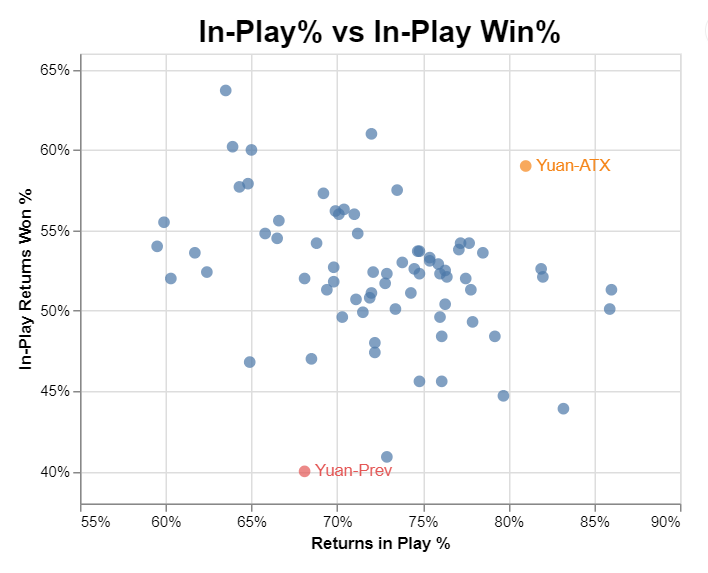

With our new sense of what these numbers mean, let’s take another look at Yuan’s step forward. The limited data at hand includes five of her matches from before this week, which we can compare to the quarter-final and final from Austin. Here’s the same graph, but with points added for Yuan’s sample of previous matches (Yuan-Prev) and for the two in Austin (Yuan-ATX):

Um, yeah. Wow. There are caveats, of course: It’s just two matches, and neither Wang is a particularly stellar server. (On the other hand, Yuan’s previous opponents were middling servers as well.) If this shift is even a little bit sustainable, Yuan will no longer be just a fringe figure on tour.

Runaway momentum

While we’re extrapolating from too-small sample sizes, I’ll give you another one, one that doesn’t paint such a rosy picture for last week’s champion.

Break points go to the returner more often than return points in general, because more break points are generated against weaker servers (or by stronger returners, or both). The women currently ranked in the top 50 win 44.4% of their return points, and they convert 46.3% of break points.

Yuan, in 33 tour-level matches since this time last year, has won 44.3% of her return points, but only 43.2% of her break point chances. A gap of three percentage points (between 43% and the expected 46%) is statistical shorthand for too many missed opportunities. I checked those numbers only because the Austin champ, in both the quarters and the final, showed signs of letting momentum get away from her. Against Wang Yafan, she got broken right after securing the first set, then struggled to regain the advantage. In the final, she served for the title at 5-2 in the second set, dropping serve twice before finishing the job in a tiebreak.

As I say, these are small samples. We tend to ascribe too much importance to hot and cold streaks–they would arise even if every point were decided by a roll of the dice. (I suffered through an epic Chutes and Ladders slump yesterday, probably because of the clutch play of my four-year-old opponent.) Still, there’s some evidence that Yuan struggles under pressure, even if she overcame it several times last week.

In this context, there’s a bit of negative spin we can put on all those returns in play. I’ve written before that momentum (and clutch, and streakiness, all that stuff) is tough to measure in tennis because the structure of the sport is anti-streak. If you hit a good serve in the deuce court, you have to hit one in the ad court. Four aces in a row? Congrats, you get to do something else now–you might even have to sit down for a couple of minutes. And that’s to say nothing of your opponent’s ability to give you shots other than the ones you’re hitting well.

But against her compatriots last week, Yuan inadvertently created conditions in which streaks could take root. All those returns in play–combined with a fair number of longer points that developed on her own serve–reduced the separation between serve and return. From 5-2 in the second set of the final, Yuan’s backhand went awry, and there was little she could do to avoid it. Her own serve wasn’t imposing enough to end points quickly, and she was out of the habit of taking big cuts on return. It was easy to get into a rut.

The momentum eventually shifted, of course. Yuan won 12 of the last 15 points of her quarter-final, and in the final, she won 10 of 12 points from 5-6 in the second set to reach 6-1 in the tiebreak. She pried herself out of one pattern and immediately found a different one, one that still largely avoided short points but ended in her favor. Yuan’s conservative returning paid off on paper, but the unending string of long(ish) points may have made it harder for her to regain control on the few occasions that she lost it.

Yuan’s fellow champion last week, Katie Boulter, already stumbled at her next obstacle, losing a straight-setter yesterday in Indian Wells to Camila Giorgi. Yuan’s first test in the desert is Varvara Gracheva, a middling server who could prove susceptible to the Chinese woman’s improved game. Next up would be a tantalizing second-rounder with China’s number one, Qinwen Zheng. Zheng’s intimidating–if erratic–serve could tell us a lot more about just what Yuan is now capable of.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: