Sebastian Baez is a marvel. In an era dominated by tall, all-court sluggers, the five-foot, seven-inch Argentinian has carved out a place on the circuit as a throwback clay-court specialist. Just a couple of months past his 23rd birthday, he has already won six tour-level titles and reached a new career-best ranking of 19th on the ATP computer.

The obvious comparison is Diego Schwartzman, another Argentinian on the small side who won titles and reached a French Open semi-final by grinding out victories and swinging above his weight. Schwartzman eventually cracked the top ten, but when he was Baez’s age, such a milestone looked extremely unlikely. When he turned 23, he stood outside the top 60, heading back to South America for another cycle through the continent’s late-season Challenger swing. He wouldn’t reach the top 20 for another two and half years.

If we assume Baez continues to improve throughout his mid-20s in the same way that Schwartzman did, a single-digit ranking seems achievable. He’s already 11th on tour in clay court Elo. Only a few players ahead of him on the official ranking table are younger.

The main stumbling block is the natural ceiling on dirtballers. There are far more ranking points available on hard courts than on clay, and one of the prime opportunities on the Argentinian’s favorite surface, in Madrid, plays fast because of its altitude. (Baez has competed there only once, losing in the second round last year to another sterling clay-courter, Stefanos Tsitsipas. Schwartzman never won more than two matches there, either.) For Schwartzman to gain a top-ten place, he needed more than a Roland Garros semi-final: He had recently reached indoor finals in Vienna and Cologne, and he was 14 months removed from defeating Taylor Fritz for a hard-court title in Los Cabos. Diego’s magic somehow worked on all surfaces. Even in a year when he posted outstanding results on clay, that was his only route to a single-digit ranking.

Baez owns one hard-court championship, from last year’s US Open warmup in Winston-Salem. But apart from that week, his story diverges from Schwartzman’s, with a career record on the surface of just 17-33. He has never won two completed matches at any other tour-level hard-court event. (His two third round appearances at majors were aided by retirements.) The Argentinian can be a star and a national hero without all-surface success, but surely he wants more. Can he achieve it?

Surface and speed

When I wrote about surface sensitivity a couple of weeks ago, Baez didn’t stand out as an extreme. Tsitsipas and Lorenzo Musetti were the men whose results were most dependent on slow courts. The numbers showed that Baez does better with a slower bounce, but the effect is less than half of what it is for Tsitsipas. The 23-year-old is more closely comparable in this department to Daniil Medvedev, who doesn’t like to play on clay–or eat it.

However, that analysis left out one major factor. I simply rated tournaments by the degree to which they helped servers end points quickly, regardless of surface. Indian Wells, on hard courts, came out as just barely speedier than Rome and slower than Madrid. Miami and the US Open were roughly equivalent to the Caja Magica as well.

Intuitively, there is more than one dimension to player preferences. Some men might just want more time to prepare, as could be the case with Tsitsipas and his one-handed backhand. But others–Baez among them–are much more comfortable on a certain type of surface, because of the type of bounce, the footing, or both. When we reduce surface type and speed to one variable, Baez and Medvedev come out equal. When we separate type from speed, they look very different.

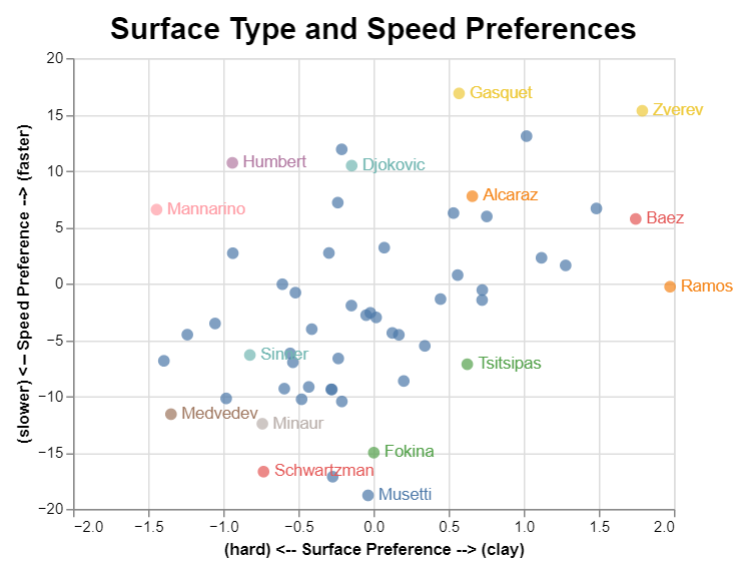

This scatterplot shows 56 players on the two dimensions:

(The units are regression coefficients and essentially meaningless out of context. They do, however, show direction and magnitude of each player’s preferences.)

Among players with at least 100 tour-level matches since 2021, Baez ranks third in the degree of his preference for clay courts, behind Albert Ramos and roughly tied with Alexander Zverev. Once surface type is controlled for, he prefers faster courts. Santiago, where he won the title last week, is one of the quicker clay courts on the circuit, giving servers as many quick points as Wimbledon (really!). Rio de Janeiro, the site of his triumph the week before, is also faster than the average dirt, rating about the same as Indian Wells.

Medvedev is the exact opposite. Only Adrian Mannarino has a stronger demonstrated yen for hard courts. Once his choice of surface is secure, though, the Russian wants it as slow as possible. Only a few players (including Musetti and another slow-hard-specialist, Alex de Minaur) are so extreme.

Schwartzman–the model for a potential all-court Baez–prefers clay, and he likes all of his courts slow. His performance is even more speed-dependent than Medvedev’s, but his surface type preference isn’t nearly as strong as that of his younger countryman.

This is all rather abstract, and to some degree, it’s just a fancy way of saying that Baez struggles on hard courts. Let’s make things more concrete by looking at what happens when the Argentinian shifts to the tour’s more popular surface.

Translations

Hard-court tennis is more serve-dominated than the clay-cout variety. The typical tour regular wins, on average, 3% more service points on hard than on clay: 4% more first-serve points and 1% more second-serve points. They win 7% fewer return points. (That sounds like a paradox, since the serve and return numbers are different. The catch comes from specifying “tour regulars”–part-timers on hard courts have bigger serves than their equivalents at clay events.)

Here are the player-specific numbers for each man in the top 20 (except for Ben Shelton, who hasn’t played much on clay). The figures are ratios of each hard-court metric to the corresponding clay-court metric–serve points won, first-serve points won, and return points won–so the higher the number, the bigger the difference in favor of hard courts.

Player SPW 1st SPW RPW Ugo Humbert 1.10 1.08 0.95 Novak Djokovic 1.09 1.11 0.91 Alex de Minaur 1.08 1.08 0.99 Daniil Medvedev 1.06 1.07 0.98 Jannik Sinner 1.06 1.08 0.95 Tommy Paul 1.06 1.08 1.08 Grigor Dimitrov 1.06 1.04 0.95 Holger Rune 1.05 1.06 0.92 Taylor Fritz 1.05 1.09 0.93 Alexander Zverev 1.05 1.03 0.89 Player SPW 1st SPW RPW Alexander Bublik 1.05 1.04 1.04 Karen Khachanov 1.05 1.09 0.96 Andrey Rublev 1.05 1.05 0.94 Hubert Hurkacz 1.04 1.02 1.00 Frances Tiafoe 1.03 1.05 0.95 - ATP Regular - 1.03 1.04 0.93 Carlos Alcaraz 1.02 1.02 0.92 Stefanos Tsitsipas 1.02 1.03 0.89 Casper Ruud 1.01 1.04 0.91 Sebastian Baez 0.94 0.96 0.85

Baez is… different. Everyone in the top 20 wins more serve points on hard courts than on clay except for him. Only a few other men on tour have the same “backwards” split, and only Federico Coria is close to Baez in the degree of his weaker hard-court service performance. What costs the Argentinian even more is how his return numbers suffer away from clay. Almost everyone wins fewer return points on hard, but Baez takes the cake here too.

Perhaps needless to say, there’s no way that this can work. Baez wins about 62% of service points on clay, a respectable number and an impressive one for someone his size, but still below the average of a top-50 player on the surface. To win even fewer on hard suggests that he would struggle even at Challenger events. At Winston-Salem last August, Baez won 63.5% of his serve points and over 43% on return. That’s a combination that will win matches; he just hasn’t provided any evidence that he can pull it off once he crosses back out of North Carolina.

Growth rate

The one reason for optimism is that Baez is young, inexperienced on surfaces other than clay. Like Schwartzman, he grew up playing on dirt, and he rose through the rankings by winning South American Challengers, then picking up victories on the continent’s Golden Swing. Maybe there’s a necessary transition period?

Here are the same ratios as above, now by season for our two Argentinian heroes:

Player Year SPW 1st SPW RPW

Diego 2015 1.01 0.99 1.01

Diego 2016 1.04 1.07 0.94

Diego 2017 1.08 1.09 0.91

Diego 2018 1.03 1.03 0.89

Diego 2019 1.08 1.09 0.94

Diego 2020 1.03 1.03 0.85

Diego 2021 1.02 1.03 0.95

Diego 2022 1.01 1.04 0.89

Diego 2023 1.09 1.08 0.88

Player Year SPW 1st SPW RPW

Baez 2022 0.91 0.94 0.82

Baez 2023 0.96 0.99 0.88

Baez did close the gap between his hard-court and clay-court performances in his second year on tour. But he still shows a more marked surface preference than Schwartzman ever did. As soon as Diego arrived on tour, he was able to win more service points on hard courts–roughly the same ratio as the typical tour regular. Baez isn’t even close. Schwartzman had to retool his game to succeed on hard courts, and Baez will need to do so even more.

The 23-year-old truly is a throwback, an undersized grinder who spins in his serves, plays defense, and constructs points. It’s a joy to watch, and the package makes him one of the best players on tour for the 14 weeks or so each year when there are top-level clay events on offer. It doesn’t, however, work so well when there’s no dirt to kick out of his cleats. Fortunately Baez is young, and he has many years left to figure it out. He’ll need to.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email:

Yes, Baez, because of his limitations in the modern game, has had a great career if he retired tomorrow. Obviously, he would disagree, and he rightfully should. But I just don’t see it. I hope I’m wrong. But he simply gets blown off any other court but clay. Perhaps the moxie he possesses will help matters.

Hi. Come on. He is just 23 and he already is a hard surface atp champion. He has won six! Atp tournaments. At least give him two year and a half for improving his hard court service (while winning more atps). The best phisical age for a player is from 23 to 28. So from 26 to 28 baez has time for his best hard surface era.