With the 1973 South African Open just a couple weeks away, the country’s racial policies were back on the sports page. On October 31st, Arthur Ashe learned that he was granted a visa to travel to Johannesburg; the government had said no in 1970 and 1971 because of the player’s “antagonistic attitude” toward the country’s leadership.

The next day, November 1st, an ILTF committee voted to allow South Africa to remain in the Davis Cup competition. Banned in 1971 and 1972, the Springboks returned to action in the 1973 South American zone and sent a second-string squad to Uruguay, where Guillermo Vilas and the Argentinian team ended their bid for the Cup. In 1974–actually, even before the new year–the South Africans would return, this time opening their campaign against Brazil.

The vote was something of a slap in the face to Argentina. The 1973 tie had barely come off: In the run-up to the matches in April, protests at home had driven the government to switch the venue to neighboring Montevideo. Now, Argentina refused to play the apartheid nation anywhere. The committee’s compromise was that it would not penalize nations for defaulting to South Africa. Between the objections of Argentina and Chile, which had said it would not play South Africa in 1973 before the issue was rendered moot, a default seemed likely to occur.

The decision, made at an ILTF meeting in Paris, had repercussions on yet another continent. New Zealand hoped to host the 1974 Federation Cup, the women’s team event. But the Kiwi government wasn’t willing to host a South African team until the pariah nation allowed multiracial competition.

Ashe’s visa was one of many signs that South Africa was willing–if barely–to consider change. The other marquee sporting event on the country’s calendar was a light-heavyweight boxing match between local hero Pierre Fourie and champion Bob Foster, a black American. The bout, scheduled for December 1st in Johannesburg, would have been unthinkable just a few years before. Throughout 1972 and 1973, South African sporting bodies gradually allowed interracial competition and hosted mixed-race teams, such as New Zealand’s All Blacks and a group of British cricketers. A handful of non-white locals were given places in the South African Open draw, as well.

It remained to be seen whether the policy shift represented a new approach, or was merely a sop to international opinion. South Africa had been excluded from the Olympics since 1964, and the country took it hard. Compromise was on the table for international competition if it would get them back in the world’s good graces. But at the local level, sport was still ruled by apartheid. The government supported a massive fund-raising effort to support black athletic development, while simultaneously seeking to broaden the scope of the Group Areas Act–part of the legal basis for racial separation–to make it harder for black teams to compete against white ones.

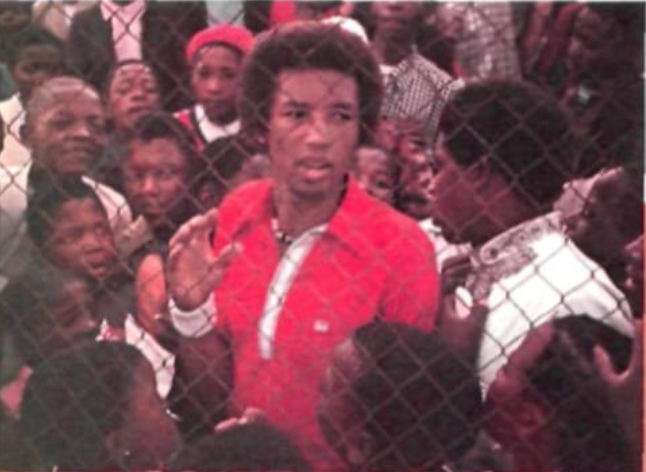

Ashe assured his hosts that his aims weren’t political. The purpose of his trip, he said, was “solely to play tennis and to do so in a spirit of goodwill and cooperation.” He would discover an enormous amount of goodwill waiting for him in South Africa, but genuine cooperation–especially for the 20 million blacks who would remain in the country long after the tournament was over–was much tougher to find.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: