I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. Hope I didn’t forget anybody…

* * *

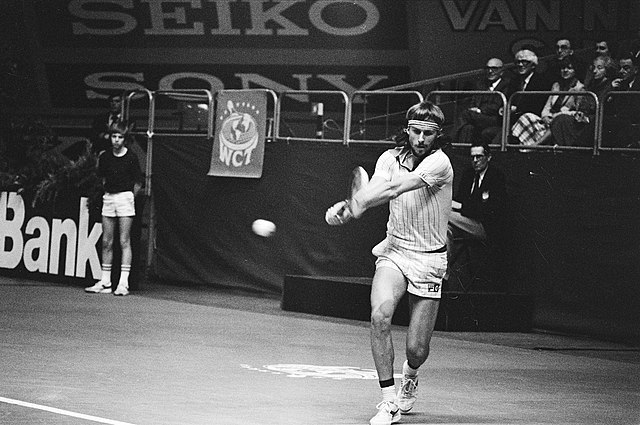

Björn Borg [SWE]Born: 6 June 1956

Career: 1972-81

Plays: Right-handed (two-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1977)

Peak Elo rating: 2,473 (1st place, 1980)

Major singles titles: 11

Total singles titles: 66

* * *

The tennis boom of the 1970s had many origins. Open tennis revitalized the sport, pitting amateur stars like Arthur Ashe against living legends such as Rod Laver and Richard González. Television discovered tennis in a big way, putting high-profile matches in prime time slots. Billie Jean King made the sport as popular among women as it was among men.

Also: Björn Borg was really, ridiculously good looking.

Tennis has always had its leading men. Even before the freewheeling 1960s, those men rarely had to look far to find adoring female fans. Borg took things to a new level. When his blue eyes and long blond hair touched down at Wimbledon, it was the athletic equivalent of the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show. Before he was the Viking God, he was the Teen Angel.

Within a few years, the Swede transcended tennis entirely. “He was bigger than the game,” said Ashe. “He was like Elvis or Liz Taylor or somebody.”

Ironically, the ultimate celebrity product of the Open era–a man who could win Wimbledon every year while still earning hundreds of thousands of dollars in prize money–still found a way to butt heads with the establishment. The World Championship Tennis (WCT) circuit, like the modern-day ATP, tried to prevent its stars from playing lucrative exhibitions that conflicted with its own events. Borg, as much as any other player in those superagent-driven years, chased the money, lawsuits be damned. In 1976, he sprinkled his season with a whopping 28 exhibition matches.

While Borg was never going to last into his thirties, his differences with the powers that be hastened his departure from the game. “Every tournament I was playing in 1981,” he later said, “I didn’t care.” He still considered taking on a limited schedule in 1982. But a new rule stipulated that he needed to commit to at least ten events. Unwilling to cave, the reigning French Open champion was forced into the odd course of playing qualifying rounds at his home tournament in Monte Carlo.

That was his last sanctioned event of the season. Instead of Roland Garros and Wimbledon, the Swede played more than 30 exhibition matches around the globe in 1982. The results didn’t matter–Vitas Gerulaitis finally beat him, something the American had rarely managed even in practice–but he was no longer playing for glory.

Back in 1974, Laver got his first good look at the intensity that Borg brought to every point of every match that the 17-year-old played. “If you play this hard,” warned the Rocket, “your mind will be drained, you’ll burn out in seven years.”

Laver was right. But oh, what a seven years it was!

* * *

Sweden didn’t need Björn Borg to put it on the international tennis map. Sven Davidson won the French Championships in 1957, and a group led by the stylish Jan-Erik Lundqvist went deep in the European Davis Cup competition throughout the early 1960s. The country even had a “Little Wimbledon” in the resort town of Båstad.

Nonetheless, it would always seem that Borg had come out of nowhere. His two-handed backhand didn’t owe a thing to Davidson or Lundqvist. His first coach, Percy Rosberg, was skeptical of a game built on topspin.

“Snow will stick to the ball up there,” Rosberg would say as he chased down yet another looping forehand.

The young man hit hard, and Rosberg wasn’t the only one who spotted something fearsome in his eyes. He would practice until he was ordered off the court. It never occurred to him to balance tennis with other pursuits; he ignored his schoolwork until his athletic schedule finally demanded that he drop out entirely.

Borg with coach, manager, and Davis Cup captain Lennart Bergelin after securing the 1975 Davis Cup for Sweden

In 1972, the 15-year-old played his first Davis Cup rubber, defeating Onny Parun of New Zealand in five sets. A year later, he made the final at Monte Carlo and reached the quarter-finals at boycott-weakened Wimbledon, where he took Roger Taylor to five sets. In Stockholm that November, he beat both Ilie Năstase and Jimmy Connors to reach another final. American Tom Gorman needed a third-set tiebreak to finally stop him.

Borg signed with the WCT circuit in 1974. In four months, he won two titles, beat Laver and Ashe, and reached the title match of the WCT Finals in May. British player Mark Cox, one of his many victims, summarized the early Borg game:

[I]t’s very difficult to get on him because he keeps coming at you, putting on the pressure, and you can’t get any rhythm. Of course, he still doesn’t think; he is smacking, smacking the ball always. He plays with a total lack of inhibition, strictly on talent and inspiration, and it’s enough.

The Swede didn’t need to be a tactical genius to win matches. Still, Cox was not the last opponent to underestimate Borg’s savvy. Some men had a sense of when it was time to switch to Plan B. Björn’s Plan A was so strong that he needed only to recognize he ought to stick with it. In the 1974 French Open final, he dropped the first two sets to Spanish veteran Manuel Orantes. Other tyros would have changed things up–or simply accepted their fate. Borg noticed that Orantes looked exhausted, and stuck with the game that put him the 0-2 hole. He won the remaining three sets, 6-0, 6-1, 6-1.

* * *

Borg didn’t need much in the way of tactics to win on clay. His topspin overwhelmed everyone except for Guillermo Vilas, and in a long match, Vilas wasn’t strong enough to hang with the hyper-fit champion.

Only one man, Adriano Panatta, would ever beat Björn at Roland Garros. Borg ultimately picked up six French titles, one of his many records that would appear untouchable until Rafael Nadal knocked them down. In 1978 and 1980, Borg didn’t lose a single set in Paris. In those fourteen matches, only the big-serving Roscoe Tanner even took him to a tiebreak.

After losing to Connors at the 1976 US Open, the Swede won 99 consecutive completed matches on clay. He didn’t lose again on dirt for nearly four years.

On grass, the game seemed almost as simple. It just took Borg a bit more time to learn it. He showed up for Wimbledon in 1976 with a new and improved attacking game. “I volley big and tough now,” he said. He didn’t lose a set at the All-England Club that year. He destroyed Vilas in the quarters, out-blasted Tanner in the semis, and brushed past Năstase in the final. Against the Romanian, he came in behind every one of his first serves. He won more than 70% of them.

“They should send Borg away to another planet,” said Năstase. “We play tennis. He plays something else.”

Borg never mastered the Wimbledon grass to the degree he conquered clay. But that’s a bit like saying Rembrandt painted better than he drew. Björn didn’t lose another match at the Championships until 1981, when John McEnroe beat him in the final.

In the interim, he played a stunning pair of five-setters to win the 1977 title. Before outlasting Connors in the final, he was pushed to 8-6 in the fifth by Gerulaitis in the semis. Commentator Dan Maskell considered the semi-final to be the best match he’d seen in fifty years at Wimbledon. That judgment lasted all of three years, until Borg came out on top of another epic.

(Yes, I know I posted this in the McEnroe article a few days ago, too. You don’t want to watch it again? You cannot be serious!)

In the 1980 final, McEnroe saved seven match points and won a fourth-set tiebreak, 18-16, that stands alone as the sport’s greatest ever. The Swede withstood the American at his explosive best, holding off still more break points for a fifth-set advantage. After three hours and 53 minutes, he took another 8-6 deciding set, his fifth consecutive Wimbledon title, and his third straight French-Wimbledon double.

* * *

You might have noticed a thread running through these highlights. When Borg wasn’t plowing through the field, dropping a handful of games per match, he played his share of fifth sets. Even though there’s some selection bias in the ones I’ve mentioned, he was stunning at the end of marathon matches.

The Swedish ironman won five-set finals to secure the 1974 French title, as well as Wimbledon in 1977, 1979, and 1980. He endured another against Ivan Lendl to win at Roland Garros in 1981, then went five to hold off Connors in the Wimbledon semis. And that was the year he didn’t care.

All told, Borg won 26 of his 32 career five-set matches. He somehow arrived on tour with the mental equipment to go the distance: He won 11 of his first 12, all before his 19th birthday. Losing two in a row didn’t faze him, either. He bounced back to beat his idol, Laver, in a crucial match at the 1975 WCT finals. He reeled off another 12 in a row*–a streak that spanned more than four years–before McEnroe finally stopped him in the 1980 US Open final.

* One contemporary report claims that he won 13 straight five-setters. It’s possible I’m missing one.

The US Open was the only tournament where Borg dropped more than one fifth set. Giant-killer Vijay Amritraj ousted him in 1974, and McEnroe beat him for the title in 1980. The Swede never did win the title in Flushing. When he lost to Amritraj, he could blame the surface–the Open was still held on grass. From 1978, he could once again point to the conditions: speedy new DecoTurf hard courts.

But for three years in between, the US Open was played on clay. Ersatz Har-Tru dirt, yes, but Björn had won plenty on that, too. Instead of cleaning up, he lost to Connors in 1975 and 1976, then exited with an injury in 1977. By 1980, when Borg finally won a high-profile event at Madison Square Garden, his struggles in the Big Apple had long looked like a jinx.

It’s important to keep some perspective here. The Swede did reach four finals in six years. For the man who won 11 of the 18 majors he entered outside the United States, though, it is a conspicuous oh-fer. Some of the blame goes to Connors and McEnroe, who played great tennis at their home event. Also, by September each year, Borg had usually picked up an injury or two. Borg and McEnroe had entered the 1980 edition with so many health complaints that Connors described the final as “two gimps battling it out.”

Björn’s main problem with the US Open, I suspect, was the same thing that had handicapped nervy players in New York for decades. It has always been the in-your-face slam, the event where it’s impossible to hide from the press, the crowds, the big city. Borg, the prime idol of them all, knew how to hide in Europe. Before Wimbledon each year, he went through a carefully choreographed fortnight of preparation, rarely stepping out of his hotel room for anything other than a practice session. In New York, he couldn’t control his surroundings to the same extent.

He would have figured it out eventually, just as his finicky rival Lendl did. But as he would increasingly ask himself: Why bother?

* * *

It’s no wonder that by 1981, Borg didn’t care. His near-decade of top-level tennis was as intense as anything a player had ever sustained for such a long period of time. The pre-Open era pros might have worked harder for a year or two at a time, but aside from Laver, González, and Ken Rosewall, they remained at the top for only a short time.

By the standards of the all-time greats, the Swede’s career was indeed short. Bill Tilden played competitively for his entire life. Most of the handful of champions who piled up more slams than Borg did–the Big Three, Navratilova, Serena, and so on–spent twice as long on tour.

But we need to keep “short” in perspective. Borg was both a global heartthrob and a single athletic focal point in his native Sweden. Every move he made was tracked, speculated upon, and blown wildly out of proportion by tabloids all across Europe.

When Borg first announced his retirement, he had been on tour for about nine years. The Beatles–perhaps a better measuring stick than any mere sporting idol–lasted only eight.

Though Björn faded from view–sort of, as he attempted various comebacks and played a steady stream of exhibitions–his playing style did not. When he was a teenager, his two-handed backhand was barely more than a novelty. A decade later, he, Connors, and Chris Evert had made it the standard option for baseliners.

Borg arrived on tour as one of the fittest guys around, the player willing to practice more than anyone else. By the time he quit, Vilas was suffering through even more brutal sessions, and Lendl was organizing his life around tennis with a single-mindedness that surpassed the Swede’s.

That level of intensity, on and off the court, would eventually come to define men’s tennis. As late as the Pete Sampras era, top players would talk about coasting on some points to save energy for others. You don’t hear that much anymore. No one presaged the first-ball-to-last-ball pressure of Rafael Nadal–or David Ferrer for that matter–more than Borg.

In 1983, Vitas Gerulaitis lamented the increasing homogeneity of the tour. “In five years tennis is going to be very boring,” he told journalist Michael Mewshaw. “We’ll have a draw with 128 Borgs.”

I’m not sure what Vitas would think of the game in 2022. There is certainly less variety than there was back when he was challenging the original Big Three of Borg, McEnroe, and Connors. The preferred tactics these days are absolutely more Björn than Johnny Mac. The standard of play–especially among the rank and file–has risen enormously as well. Even the men who skimp on topspin or cling to a one-handed backhand have, in their match preparation and their on-court demeanor, become more like the Swede.

A draw of 128 Borgs? We’re not quite there yet, but Björn, more than any player of his era, offered a glimpse of the future.