I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. Whee!

* * *

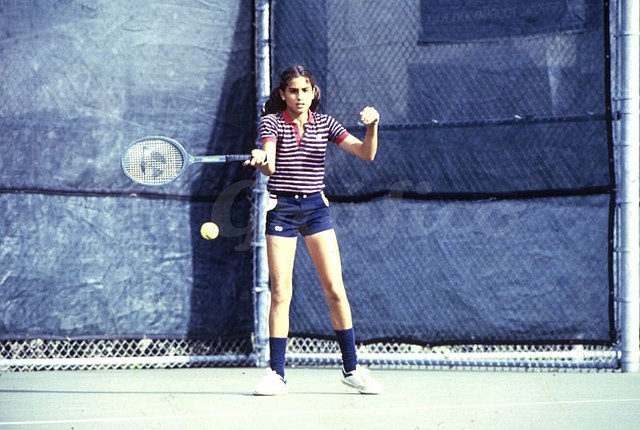

Gabriela Sabatini [ARG]Born: 16 May 1970

Career: 1985-96

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 3 (1989)

Peak Elo rating: 2,418 (2nd place, 1991)

Major singles titles: 1

Total singles titles: 27

* * *

Graf-and-Sabatini, Sabatini-and-Graf. If you heard one of those names in 1985 and early 1986, you probably heard both. Everyone agreed that Gabriela Sabatini and Steffi Graf were the future of women’s tennis. No one was quite willing to choose one over the other.

In the middle of 1985, Sabatini had just turned 15. Graf was a year older. The smart money leaned toward the Argentinian. Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova, and others as far flung as Ted Tinling and Pancho Segura considered Sabatini the greater natural talent. John Feinstein of the Washington Post reported an insider consensus that “she could be the player who combines the elegance and grace of Evert with the athletic ability of Martina Navratilova.”

Gabi didn’t waste any time establishing herself on the adult tour. At Hilton Head in 1985, she beat top-tenners Zina Garrison, Pam Shriver, and Manuela Maleeva in succession before falling to Evert, 6-4, 6-0. Even in the final, she made Chrissie work for it. At the French Open, two weeks after her 15th birthday, she reached the semi-finals before falling to Evert again.

After she retired, Sabatini admitted that as a junior, she was so shy that she would lose matches on purpose to avoid giving a speech after the final. None of those nerves were visible when Gabi’s big topspin groundstrokes earned her one victory after another.

“She is not normal,” said Patricio Apey, the former Davis Cupper from Chile who served as her coach and manager at the time. “She is a Martian.”

If pressed, a few experts would favor Steffi over Gabi in those early days. Evert thought that Graf “probably wants it a little more,” and Tinling pointed to her stronger mental game. (Not everyone could be nudged in the German’s direction–Navratilova said “she does strange things out there.”) Sabatini had her blemishes, most notably a cream-puff second serve and a reputation for running out of gas late in matches.

It wasn’t until mid-1986 that Graf’s superiority became apparent. Even then, Gabi stayed on her heels longer than almost anyone. Steffi won their first eleven encounters, but Sabatini took seven of the first eight to three sets. The first time they met in a final, Gabi came within one point of a straight-set victory.

Fast-forward a decade, and the debate was long over. The two women met constantly between 1985 and 1995, and Graf won nearly three out of four. The German won 22 majors to Sabatini’s one. Sabatini’s top-line stats don’t seem to merit a place among the three dozen greatest tennis players of all time. It’s useful to review the conventional wisdom about the two prospects because it reminds us that Gabi’s timing was catastrophically bad.

No one else had to play Steffi Graf forty times.

* * *

The case for Sabatini rests on the argumentum ad propemodum. That’s Latin for “argument from almost,” an ancient rhetorical technique that I just made up. The basic idea: If A is almost as good as B, and B is outrageously good, A must be pretty darn good too.

It’s not the sort of strategy that sways the hearts and minds of the masses. But we must follow the facts where they lead us.

It’s far more satisfying to say that a player is great because she won all the majors, dominated her rivals, and inspired children far and wide. Alas, there aren’t that many all-timers who meet that standard. An awfully small number of superstars have spent the last century keeping the rest of the field under their collective thumb.

Sabatini and Graf playing doubles at the 1986 French Open

So, in a 128-player list, we have plenty of one-slam winners and a sizable helping of slamless wonders. There are stars who seized a moment when the field was weak and others who managed to puncture–however briefly–the imperiousness of one of those all-galaxy legends.

Gabi falls into the latter group. She’s the queen of the “almosts.”

Her career record against Steffi was 11-29, one of the best marks anyone managed against the German. I’ve already told you one way in which it was closer than it looked, all those three-setters in the early going. In fact, only 15 of Graf’s 29 victories came in straights.

A big part of Sabatini’s case for greatness–and the reason her peak Elo rating ranks 11th among Open-era women–is a nearly two-year span from the 1990 US Open to April 1992. Here’s how she fared against Graf during that time:

Year Event Round Winner Score 1990 US Open F Sabatini 6-2 7-6(4) 1990 Zurich F Graf 6-3 6-2 1990 Worcester F Graf 7-6 6-3 1990 Slims Championships SF Sabatini 6-4 6-4 1991 Tokyo Pan Pacific QF Sabatini 4-6 6-4 7-6 1991 Boca Raton F Sabatini 6-4 7-6 1991 Key Biscayne SF Sabatini 0-6 7-6 6-1 1991 Amelia Island F Sabatini 7-5 7-6 1991 Wimbledon F Graf 6-4 3-6 8-6 1992 Key Biscayne SF Sabatini 3-6 7-6 6-1 1992 Amelia Island F Sabatini 6-2 1-6 6-3

That’s eight for Gabi, three for Steffi. Sabatini beat her nemesis on hard, clay, and carpet, and she came within two points of defeating her for the 1991 Wimbledon title.

Some people find it easy to play down this rivalry-within-a-rivalry. Graf had a tough 1990. She hurt her right hand, she underwent surgery to correct a sinus problem, and a paternity suit against her father kept the German tabloids in a lather for months. None of that helped her game.

On the other hand, Steffi managed just fine against everyone else. From July 1990 to the 1992 French Open semi-finals, Graf’s record was 132-13. That’s a healthy 129-5 against everyone not named Sabatini. Only three other women beat her: Navratilova, Arantxa Sánchez Vicario, and Jana Novotná (three times). The German reached 20 finals and converted 16 of them. Gabi won the other four.

Monica Seles took over the number one ranking in March 1991, but she owed her position in part to Sabatini’s attack on Steffi’s point total. Monica might not have been able to do it herself, at least not so soon: Seles and Graf met twice in that span, and Graf won both times.

* * *

Debates about that eleven-match sequence can get a little circular. Did Sabatini finally make headway because Graf was injured, distracted, or otherwise slumping? Did Steffi only appear to be more fragile because Gabi had reached a new level?

Graf’s 129-5 record against everybody else suggests the latter. No one can remain as untouchable as the German had been between 1987 and 1989, in large part because of the enormous target painted on her back. But Steffi came close, especially when she faced non-Argentinian opponents.

One thing is clear: Sabatini never considered Steffi insurmountable.

She doesn’t get enough credit for her efforts to dethrone the German, partly because they were not entirely successful. When they were, Seles came along to ensure that Gabi would never reach number one herself. Another complicating factor was that, in the public eye, Sabatini was better known for her looks than her backhand. Ted Tinling, who had swooned for charismatic starlets as far back as Suzanne Lenglen, said:

There’s a great arrogance about Sabatini, and it all shows in the carriage of her head. She looks almost goddesslike. Taken together, her beauty and her arrogance form a contradiction. And I don’t think one should try to solve a contradiction in a beautiful woman. One has simply to accept her as she is.

So, right. Enough about that.

Patricio Apey guided Gabi from a temperamental 12-year-old to a top-tenner. He tried all the while to shield her from the pressures of international stardom and avoid the burnout and overuse injuries that had halted so many promising careers. He largely succeeded–perhaps too well. By 1987, Sabatini was itching for a more demanding coach to take her to the next level. She found one in Ángel Giménez, a former tour player from Spain.

Under Giménez’s guidance, Gabi developed the physique and stamina to match her already-physical baseline game. No longer could opponents count on Sabatini to exhaust her reserves with one long set. In her first twelve months with Giménez, she went 11-4 in three-set matches, 10-0 against everyone besides Steffi.

In the beginning of 1988, she finally caught up with Graf. The training paid off, as the Boca Raton final demonstrated. The match developed in a way that usually worked against the Argentinian. Steffi won the first set and served with a 3-2 edge in the second. Sabatini’s retrieving coaxed error after error, and not only did Gabi get the break back, she lost only one game the rest of the way.

The 2-6, 6-3, 6-1 victory was no fluke. The two women met again at Amelia Island a month later. Graf took a 3-0 lead in the final set, and once again Sabatini charged back for a 6-3, 4-6, 7-5 triumph. Steffi retained the ability to raise her game when it really mattered–she beat Gabi at the French, the US Open, and the Olympics later that year–but Sabatini had pierced the armor.

* * *

Sabatini’s greatest coup required another shift in strategy. By 1990, she was no longer making progress with Giménez; some observers felt that the physical training had gone too far. Sports Illustrated wrote that she was “moving like a stevedore.” Her tactics left something to be desired, and she still had a tendency to lose focus mid-match.

Carlos Kirmayr came on board in June, and Gabi traded the weight room for more roadwork. They developed a gameplan specifically for Graf, aiming to approach to the sidelines and force Steffi to hit passing shots on the run.

It’s easy to overstate how much of a change the new tactics represented. Journalists were always going on about how Sabatini was learning to serve-and-volley, or that she was approaching the net more confidently. Maybe so, but she serve-and-volleyed two dozen times against Navratilova in the 1986 Wimbledon semi-final. And with more aggressive intentions against Graf at the US Open in 1990, Sabatini came forward 40 times–but only once she had carefully prepared the way. The average rally length in those points was nearly ten shots. No one would ever confuse her with Boris Becker.

Still, tennis is a game of small margins. No matter how dire the head-to-head record, Gabi had never been far away.

Sabatini overcame an early semi-final deficit against Mary Joe Fernández to reach the 1990 US Open final. For the first time, defeating Graf proved to be a straightforward matter. Steffi’s typically authoritative forehand was unable to dictate play. Gabi even held on to more than half of her vulnerable second-serve points, and she won in straights.

Thus began Sabatini’s stunning eleven-match run against her rival. Only two other women–Navratilova and Sánchez Vicario–won eight matches against Graf in their careers. Gabi did it in 20 months.

* * *

Had she been less forgiving against the rest of the field, Sabatini could’ve seized the number one ranking. 1990 ended on a historic note, if not a successful one: After beating Graf–in straights, again–in the semi-finals at the Virginia Slims Championships, she lost a five-setter to Seles in the title match. It was the first five-set women’s match of the Open era, and both competitors were more than equal to the challenge.

When Seles gained the number one position in 1991, Sabatini was close, too. By my Elo ratings, Gabi came within 40 points of reaching Graf and the top spot in April–more than a rounding error, but still a narrow gap between her and a player who had reached some of the highest peaks in the sport’s history only a couple of years before.

From here, unfortunately, we return to the land of the almosts. Sabatini reached her sole Wimbledon final in 1991, knocking out her first six challengers in straight sets. She drew Graf in the final, of course. At 4-4 in the decider, Sabatini broke, and she twice served for the match. She came within two points of the title but no closer, conceding the championship to the German, 6-4, 3-6, 8-6.

After two more victories on the friendly hard courts of South Florida, Gabi never beat Graf again. In the 1992 Wimbledon semi-final, it was a routine 6-3, 6-3 decision for Steffi. Sabatini hung on to a place in the top five for another year, but she won only two sets in her final eight encounters with her lifelong rival.

Sabatini in the 1991 Wimbledon final

Another almost: At the 1993 French Open, Gabi took a 6-1, 5-1 lead over Fernández for a place in the semis. She failed to convert five match points and lost the match, 10-8 in the third. After that, said her then-coach Dennis Ralston, “The fire went out of her, and she hasn’t gotten it back.”

The Argentinian won only two more titles before calling it quits in 1996, at the age of 26.

Sabatini’s legacy is studded by the sort of stats people talk about when you don’t win major titles. She lasted more than 500 straight weeks in the top ten–fourth-best since the WTA began keeping rankings. She upset the world number one ten times–more than any other player who never reached the top spot herself.

Those are the kinds of laurels you’re stuck with if you had the bad luck to arrive on the tennis scene alongside Steffi. “Almost” might be the saddest word in sports, but don’t let it fool you. For Sabatini to come so close, so often, in one of the strongest eras of women’s tennis history, deserves more acclaim than she’ll ever receive.