In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Ilie Năstase [ROU]Born: 19 July 1946

Career: 1962-85

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1973)

Peak Elo rating: 2,256 (1st place, 1973)

Major singles titles: 2

Total singles titles: 98

* * *

Here’s a mystery you probably haven’t mulled over for a few decades: Did Ilie Năstase throw his fourth-round match at Wimbledon in 1973?

1973 was the boycott year, when 81 men skipped Wimbledon to protest the International Lawn Tennis Federation’s suspension of Yugoslav player Niki Pilić for missing a Davis Cup tie. The recently-formed Association of Tennis Professionals–the ATP–objected. Functioning more as a player’s union than it does today, it wanted to have a say in disciplinary matters. The ILTF didn’t budge.

Năstase was one of only a handful of ATP members to defy the boycott and play. He was a half-hearted participant in the union: he signed up but generally did whatever he wanted. When the organization fined him after the tournament, he explained that the Romanian Army–of which he was technically a captain–ordered him to play.

He was, by far, the best player left in the field. He had lost a thrilling five-set final to Stan Smith the year before, and he had won seven of his last eight tournaments, including the French Open, the Italian Championships, and Queen’s Club. He should’ve coasted to the title. His competition consisted of a few fellow Eastern Europeans, some prospects (including Björn Borg and Ilie’s doubles partner Jimmy Connors), and an armada of last-minute replacements.

The overwhelming favorite barely made it to the second week. Năstase lost his fourth-round match in four sets. His vanquisher was a 21-year-old American college star named Sandy Mayer, who had an injured thumb and was sneezing with hay fever. Mayer had plenty of promise, but he was nearly a decade away from reaching his career-best ranking. The day wasn’t covered in glory for anybody.

Speculation started immediately. Maybe the Romanian couldn’t have lost his opening match on purpose: That would be too obvious. Mayer was the first opponent he faced who could plausibly beat him. Năstase secretly supported the boycott–so the theory went–and lost at the first opportunity.

Ilie in uniform, at Wimbledon in 2015

There’s just as much evidence on the other side of the ledger. Ilie was hardly impregnable against second-tier opponents. In a single four-week span at the start of the season, he lost to journeymen Ove Nils Bengtson, Karl Meiler, and Paul Gerken. He managed to drop a set to unheralded Colombian Iván Molina in the second round. And he was hardly in a rush to get away from the scene of the controversy. Năstase and Connors combined to win the doubles title over the boycott-decimated field.

For his part, Năstase has never said anything publicly to support the tanking hypothesis. He wrote in his 2004 autobiography that his back seized up during the Queen’s Club final and continued to give him problems. Against Mayer, he “was not in good shape mentally or physically,” and he didn’t like playing on the upset-friendly Court No. 2.

As conspiracy theories go, it’s pretty weak sauce. Upsets happen, and while Năstase was probably the best player in the world at the time, he was never untouchable. But the question persists.

The historical mysteries that linger are always about something bigger, and this one is no exception. The 1973 Wimbledon fourth round itself is a historical footnote. But Năstase is one of the most compelling characters in the game’s history. Was he a hero or a villain? Did he defy an authoritarian government to silently support his colleagues, or was he little more than a scab acting at odds with his own union?

As for that day on Court No. 2, only Ilie knows for sure. To the broader question, the answer is both. Or neither. The Romanian was a magician, a buffoon, and occasionally, a champion of unsurpassed brilliance.

* * *

Whatever else he was, it’s important to remember that at the peak of his powers, Ilie Năstase was a huge international celebrity. In the early 1970s, he got more global attention than any other sports star save Muhammad Ali. He was the first athlete endorser signed by Nike. While his playing record never quite accounted for his worldwide fame, his undeniable charisma made up the difference.

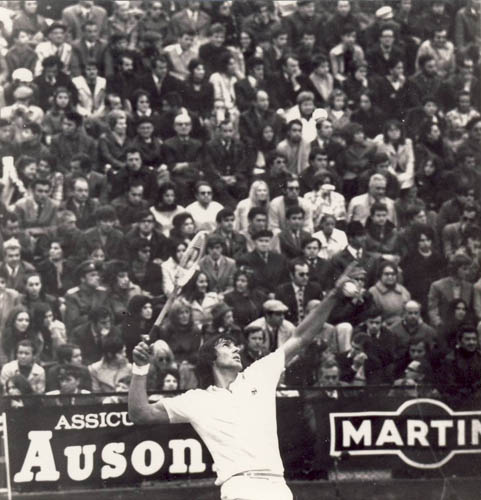

Fans who showed up, or tuned in, for a Năstase match could expect both shotmaking and showmanship. He might chase down a lob with a behind-the-back flick of the wrist, a shot that Bud Collins dubbed the “Bucharest Backfire.” If the linesman dared call it out, he might unleash a stream of profanity, commiserate with the crowd, or stage a sit-down strike until he got his way.

A Bucharest Backfire in 1969 Davis Cup competition

Ilie symbolized one possible path for fully professional, Open tennis. Everybody respected the Australians, modest champions like Rod Laver, Ken Rosewall, and John Newcombe. Yet the new big-money atmosphere of the sport made room for more colorful, controversial characters, and Năstase was the first superstar to fill the gap.

Amateur-era tennis had its bad boys, but as Sports Illustrated put it in a 1972 profile of Ilie, “Bad in tennis was always only semibad.” While rebels like Bobby Riggs and Frank Kovacs bent the rules, they rarely stepped across the unwritten boundaries. When a real problem child appeared, national federations were so powerful that they could simply get rid of the offender. At Forest Hills in 1951, an American top-tenner named Earl Cochell berated the tournament referee behind closed doors. He was banned for life.

More than a few people wished that tennis would do the same thing to Năstase. Laver said, “I don’t want my kid seeing Năstase play. The demeanor you show on the court is important to tennis…. Maybe we were too stereotyped. But we were told to behave or they’d take our racket away.”

No one ever seriously thought about taking Ilie’s racket away. He was too good for the box office. John McEnroe, another man whose entertainment value consisted of more than just courtcraft, said, “[H]e’s done more for the game than any single player who has ever lived…. You wouldn’t believe how many people come to see him.”

In the first decade of the Open era, tennis was even more fractured than it is today. Every one of the competing camps–majors, national federations, rival tournament circuits, promoters staging lucrative one-offs–needed to figure out how to make money in the sport’s new environment, and no one was ready to kill a golden goose. At one tournament, Năstase and his mentor Ion Țiriac were defaulted from their doubles match. The next day, they pulled out of the singles, saying that if they couldn’t play doubles, they wouldn’t play at all. Presto–the default was reversed, and they were back in the doubles.

* * *

It wasn’t until 2017, decades after his retirement as a player, that Năstase finally went far enough that a governing body severely sanctioned him. During a Fed Cup tie, he (among other things!) swore at the chair umpire and got himself kicked out of the stadium. The ITF banned him for four years. Even then, he turned up at the on-site restaurant the next day, and he made an appearance at the Madrid Open a few months later.

Hard to believe that when Ilie first came on the scene, the word Țiriac would use to describe him was “timid.”

Țiriac was nowhere near the level that Năstase would reach, but he was the top of the heap in Romanian tennis when Ilie learned the game. A former international rugby and ice hockey player nicknamed the Brașov Bulldozer, he realized that a tennis career would last longer, and that his legs–combined with tactical smarts, gamesmanship, and an unparalleled will to win–would keep him competitive against all but the very best players in the international game.

Năstase and Țiriac in 1987

He held the Romanian national title for nearly a decade before Ilie took it from him. Even then, in the late 1960s, Năstase looked up to the older man, and the pair traveled the European circuit together. Țiriac would tell his protégé that he needed to open up, until one day, Năstase suddenly had a personality. The veteran may have had second thoughts about that advice.

“I feel like dog trainer who teach dog manners and graces,” Țiriac said in 1972. “And just when you think dog knows how should act with nice qualities, dog make big puddle and all is wasted.”

To some degree, Năstase’s antics were a natural part of his personality. Țiriac thought so, and he cautioned against trying to change him. You could have all of Ilie or none of him.

It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that the behavior was out of his control. Psychologist Dr. Joyce Brothers said in 1976, “Năstase likes attention and because tennis has been considered a gentleman’s game, he keeps his opponents so shook up they can’t concentrate.”

He so riled up Clark Graebner that once, mid-match, Graebner motioned him to come to the net, where he smacked him. In a big-money match against Jimmy Connors, the players exchanged the usual trash talk. Finally Năstase thought his opponent had gone too far. He knew where to hurt Jimmy, saying that Connors couldn’t do anything without his mother. The momentum shift was immediate; it was all Ilie from that point on.

* * *

None of this would’ve mattered if Năstase hadn’t accumulated the results of a champion. He came close to winning his first major title against Stan Smith at Wimbledon in 1972, then took the final step at the US Open. He defeated the home favorite, Arthur Ashe, in five sets.

By 1972, no one could call Ilie timid, either on or off the court. After winning his first titles as the most dogged of clay-courters, even willing to moonball if necessary, he learned to serve and volley. He never developed the serve of a Smith or an Ashe, but he learned the tactics necessary to succeed on all surfaces.

Ashe said, “Năstase is so good that I actually can get inspired watching him play.” Fred Stolle explained, “He’s quicker than anybody. And it’s not scrambling. The guy never scrambles. It’s not much anticipation, either. It’s just all zoom. He doesn’t seem to be trying. He doesn’t do much on the volley, either. Then all of a sudden he’s there. He’s always there.”

Despite the indifferent serve, Năstase’s zoom was enough to beat tough competition on fast indoor carpet. His most impressive feat was his run of five straight finals at the season-ending Masters event between 1971 and 1975.

The first three of those, all of which he won, were played on carpet. The fields weren’t quite comparable to those at the present-day World Tour Finals because many top stars were committed to the rival WCT circuit, but they were hardly cakewalks. In 1971, he swept a round robin against the likes of Smith, Graebner, and Cliff Richey. In 1972, he went undefeated again, beating Connors and Smith in the knockout rounds. In 1973, he finally dropped a match, but made up for it with straight-set victories over Connors, John Newcombe, and Tom Okker. At the 1975 edition of the event, he obliterated Björn Borg, 6-2, 6-2, 6-1.

When the ATP debuted its computer ranking system in August of 1973, Ilie was number one, and deservedly so. He held on to the top spot for 40 weeks, until Newcombe overtook him the following year.

According to my historical Elo ratings, his legacy would look even better if the ATP had switched on the computer sooner. He earned the top spot starting in August of 1972, lost it for part of 1973, and took it back–as the official formula agrees–in the summer of that year. All told, my system gives him nearly 100 weeks at number one, an achievement that only nine players have matched since.

* * *

So, hero or villain?

If you polled the tennis world in the summer of 1972, you’d have gotten “hero” by a landslide, albeit with some famous names standing up for the opposition. After Ilie beat Ashe for the Forest Hills title, two things happened to shift the narrative.

First, Romania hosted the United States in the final round of the Davis Cup that year. Năstase and Țiriac felt that they had always been at a disadvantage when they played in the States, so they did everything they could to stack the deck in their own favor. The Romanians opted for a glacially slow clay surface, they smothered the visitors with a security detail, and they hired line judges with strong partisan preferences. Gamesmanship aside, it was Romania’s–and Ilie’s–chance to shine at the apex of men’s tennis.

The home team flopped. In the opening rubber against Stan Smith, Năstase got into an argument near the end of the first set, then appeared to lose interest entirely. He fell in straight sets. The Romanians were even more punchless in the doubles, going down 6-2, 6-0, 6-3. Năstase came out of the biggest weekend of his career looking like a clown, one who didn’t have what it took to win when it counted. It wasn’t entirely fair–Ilie played a whopping 52 Davis Cup ties in his career and won 109 matches in the competition–but the reputation was tough to shake.

The other thing that happened was the rise of Jimmy Connors. For half a decade or more, all the complaints about bad boys in tennis–and they were incessant–were about Connors and Năstase, Năstase and Connors.

Năstase and Connors as doubles partners at Wimbledon in 1974

Ilie’s nickname, inevitably, was “Nasty,” but the term was a better match for Connors. Thrilling as Jimbo was to watch, he had little of the personal charisma that allowed Năstase to get away with anything. In 1972, Sports Illustrated celebrated the potential value that a proper “bad boy” could bring to tennis. A few years later, Connors attracted even more fans, but he ensured that people were a lot more ambivalent about the value of bad behavior in the traditionally elite game.

But even in the Connors era, advocates of old-fashioned, prim-and-proper tennis couldn’t help but recognize greatness. Margaret Court, who briefly played alongside Ilie for the World Team Tennis Hawaii Leis in 1976, spoke for many of them. “Ilie Năstase is a difficult man to like. But he’s just too good.”