In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Pam Shriver [USA]Born: 4 July 1962

Career: 1978-97

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 3 (1984)

Peak Elo rating: 2,266 (3rd place, 1984)

Major singles titles: 0

Total singles titles: 21

* * *

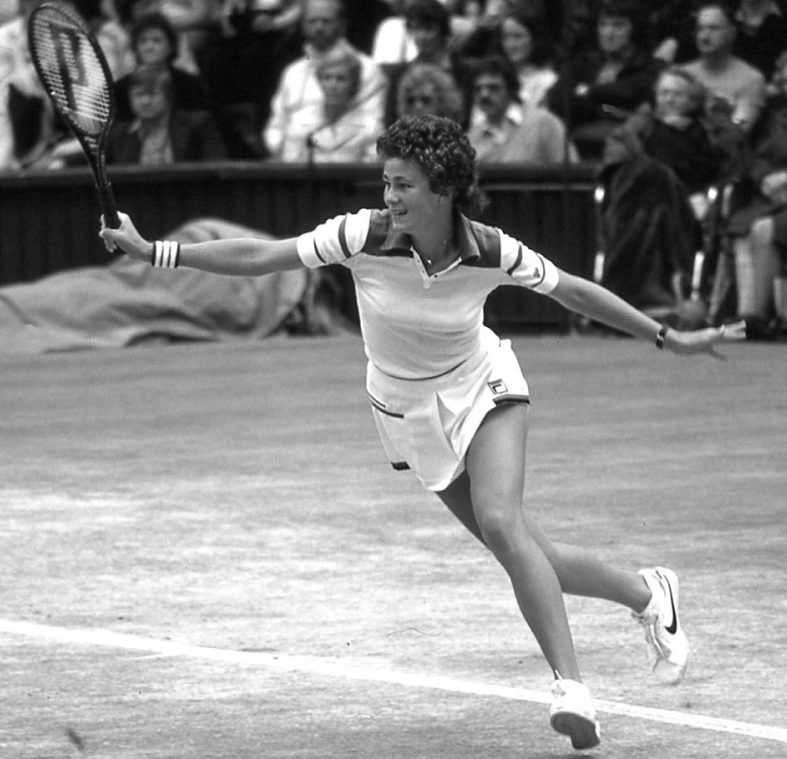

Pam Shriver was apparently the sort of player that, if you watched her in action, you just had to give her a nickname. Soon after arriving on tour, she was dubbed the “Lutherville Lamppost.” She hailed from Lutherville, Maryland, a suburb of Baltimore, and “lamppost” was the best alliterative description of a six-footer that the wags were likely to come up with.

Bud Collins did a little better. He called Pam the “Great Whomping Crane,” a nonsensical tag that is nonetheless one of his better coinages. Shriver serve-and-volleyed while the rest of her generation mimicked Chris Evert from the baseline, so she swooped into the net–just like a crane. With arms that nearly covered the breadth of the net and an oversized racket to cover the remaining inches, the swoop often did indeed end with a whomp.

One of the most articulate players off the court, Shriver couldn’t quite be pinned down as a mere lamppost or crane. She kept herself busy, often taking on obligations that other players skipped. Her longtime coach, Don Candy, dubbed her “the Florence Nightingale of women’s tennis”–a positive spin on her charitable nature and packed schedule, even if he didn’t always approve of the distractions.

Pam made her first appearance as a television commentator in 1981 (when she was 18!) and by the middle of the decade, her friends in the Republican establishment were urging her to run for office. She had so many interests away from the sport that John Feinstein suggested she go by yet another nickname: Pam “Not a Tennis Player” Shriver.

Not just a tennis player, to be clear.

* * *

One writer described the 16-year-old Shriver as “gangly as a newborn colt.” Her youth and her undisguised emotion on court–no one ever had to wonder what the young Pam was thinking–gave the impression that she was inexperienced, even naive.

Her results told a different story. She had been playing tennis for more than a decade, and she took her first lesson when she was nine years old. Candy, her coach from day one, was an unlikely character to be teaching beginners in suburban Baltimore. A canny Australian who had won the French doubles title in 1956, he would work with Shriver for more than a decade. Within a few years, she was winning matches for her high school’s boys’ team. By the time she was 15, she was considered the second-best player her age in the nation, behind only Tracy Austin. Candy felt she had nothing more to gain from junior competition.

Her coach was right. Pam started 1978, six months short of her 16th birthday, by winning a local qualifying tournament for a place in the draw of the Virginia Slims of Washington. In that first event on the circuit, she won her opening match against Pam Teeguarden and lost a close second-rounder to Virginia Ruzici. The same month she headed to a Futures event in Columbus, Ohio, where she won twelve straight matches to come through pre-qualifying and qualifying to win the title. At Hilton Head in April, she beat Teeguarden again and took a set from Martina Navratilova.

That summer at Wimbledon was her first appearance at a major. She served for the match and a place in the second week, but ultimately fell in the third round to Sue Barker, 2-6, 8-6, 7-5. She bounced back well enough to win four matches in the consolation event and reached the semi-finals. Candy said, “It takes some experience to know how to win at Wimbledon,” but Shriver would quickly prove she could accomplish great things with only a bit more seasoning than she already had.

At Forest Hills just two months later, she became the youngest finalist in the history of the event. She reached the semis without dropping a set, knocking out the Aussie veteran Lesley Hunt 6-2, 6-0 in the quarters. That earned her a meeting with Navratilova, the top seed who had already won ten tournaments that year. The 16-year-old showed a few signs of nerves, losing her serve twice, each one right after she broke Martina. But she survived two rain delays and airplane noise from LaGuardia traffic that was the worst reporters could remember.

Barry Lorge wrote for the Washington Post that she “served oppressively,” and her first serve was reliable when it mattered. She saved four set points in the opening set, and she took full advantage of her height to serve wide to Navratilova’s lefty backhand. Candy’s guidance had made her a tactician beyond her years. Martina said after the match, “She played like a grown-up, a 25-year-old.” Shriver won in two tiebreaks, 7-6(3), 7-6(3).

Pam’s opponent in the final was Chris Evert. She feared the embarrassment of losing 6-0, 6-0 in a grand slam final, but there was no reason to worry. Evert had a better handle on the serve than Navratilova did, and the decision was still a close one, 7-5, 6-4, in favor of the veteran.

A 16-year-old grand slam finalist, Shriver went back to Baltimore–and her last year of high school–thinking the sky was the limit.

* * *

Nine months after beating Martina at the US Open, in June 1979, Shriver was warming up at the grass court event in Chichester, England. She hit an overhead and felt a pop in her right shoulder. The injury would cause her to pull out of her second-round match at Wimbledon, and she wouldn’t win another match until November.

Shoulder–and later elbow–problems wouldn’t completely derail her career, but they halted her progress at just the time that she could’ve been figuring out how to challenge Evert and Navratilova at the top of the game. Instead, it was Tracy Austin who made headway while Shriver managed her injuries. Six years later, Frank Deford described her appearance at a press conference, “her one shoulder all iced up as usual, bulging like a tuberous potato.”

Shriver wrote five years later, “My right arm has become a focal point in my life, and I hate that.”

We’ll never know whether an unimpaired Shriver could’ve consistently challenged Chrissie and Martina. With her shoulder as it was, all she could do was join the scrum fighting for third place. When David Letterman asked Andrea Jaeger if she thought she could made it to number one, Jaeger spoke for many when she explained just how many tournaments she’d need to win–and how many times Navratilova would have to lose early–for the top spot to even become a possibility.

Pam lost her first 14 meetings with Evert, not claiming a set until their 10th encounter and not recording a victory until 1983. She beat Navratilova again at the US Open in 1982, but it was a mere blip in a big picture, as Martina won 41 of their 44 head-to-heads. One indication of Navratilova’s dominance is that even those three defeats made an impression on the champion. She wrote in 1985, “Actually, [Pam’s] given me some of my biggest losses, and she constantly comes up with big matches against me.”

Shriver reached nine major singles semi-finals in her career. After her initial win in 1978 against Martina, she lost four against Navratilova, one to Evert, one against Hana Mandlikova, and two to Steffi Graf. By the time she could finally hold her own against Evert, a new generation–Graf, Gabriela Sabatini, and a non-stop parade of hard-hitting teenagers–came along to make the 20-something serve-and-volleyer feel like a museum piece.

* * *

There’s another what-if in the Shriver story, one that only became public knowledge this year. In April, Pam wrote in The Telegraph that her relationship with Don Candy crossed the line into a sexual–and sometimes emotionally abusive–one. Candy, who died in 2020, was married and 33 years her senior. She is careful not to demonize her former mentor, but she is also clear about the negative effects of the relationship:

It was horrible. I can’t even tell you how many nights I just sobbed in my room–and then had to go out and play a match the next day. [Candy’s wife] Elaine would arrive just in time for the slams: Wimbledon or the US Open. Now I can see that my most disappointing results often correlated with these moments. So, even from the most pragmatic perspective, I look back and think, “Jeez, was this good for your tennis?”

She took four months off from the tour in 1984 to clear her head, rest her shoulder, and find new coaching and management arrangements. Candy retained an advisory role, and as late as 1991, Shriver still sometimes called him for advice. He told Michael Mewshaw, “When the dark clouds gather, Pam still acknowledges me.” It was one thing to recognize that a relationship is unhealthy. It was another to figure out how to replace the voice that had always been in her ear.

Shriver and Candy in 1980

The transition was not easy, but Shriver emerged to play some of her best tennis. Apart from one blip, she held on to a place in the top five on the WTA computer until March of 1989. She won multiple titles every year from 1983 to 1988.

Most importantly for her legacy, her doubles game remained unaffected.

* * *

The Tennis 128 ranking doesn’t consider doubles accomplishments, but writing about Pam Shriver without mentioning her doubles records would be almost as bad as leaving out the “Great Whomping Crane” nickname.

It’s no surprise that a tactically sound six-footer with good control of her serve and even stronger volleys would become a standout doubles player. She reached her first major final with Betty Stöve at the 1980 US Open, where the pair lost to Navratilova and Billie Jean King. The winning team soon split, and Martina plunked down a quarter to call Shriver, who had proposed earlier that year that they join forces.

Navratilova was the best doubles player of her era, probably the greatest of all time. Shriver was her strongest partner. They reached the 1981 Australian final at their first major as a team, and they won Wimbledon the same year. They would go on to win 20 slams together, including all four in 1984. Between 1983 and 1985, they won 109 matches in a row, and they took the trophy at the WTA Tour Championships ten times in a twelve-year span.

Shriver didn’t have a problem competing alongside the woman who beat her so often on the singles court:

People often ask if it’s difficult to play against Martina in singles and then team up with her in doubles. Well, it would be much worse to play against her in singles and then not team up with her in doubles.

At one point in the Navratilova-Shriver glory days, Martina said in a speech that she never wanted to play with another partner. Pam jokingly jotted it down on a cocktail napkin and got her teammate to sign it. The partnership didn’t quite last forever–after eight-plus years, Navratilova chose to play with Hana Mandlikova at the 1989 US Open. But while Shriver would’ve preferred to stick with what worked, the breakup gave her the opportunity to cement her legacy apart from Martina’s. She had already taken a doubles gold medal at the Olympics in Seoul with Zina Garrison in 1988, and 1991, she paired with Natasha Zvereva to win the US Open.

* * *

Shriver kept a journal throughout 1984, her year of inner conflict. Some of it appeared in Sports Illustrated, and it was later expanded into a book, Passing Shots: Pam Shriver on Tour. It’s one of the better tennis memoirs: candid, insightful, and often laugh-out-loud funny. Frank Deford was one of the editors on the project, and he gained some insight both into the player and his own framework for understanding athletes:

Most champions are a good deal more inner-directed than she. … It is my own view that when we journalists go prattling on about “the killer instinct,” we are really employing a colorful phrase for the more prosaic “self-centered.”

He explained, by contrast, how focused–and egocentric–Chrissie and Martina could be. Shriver couldn’t have been more different. She said in the book, “Tennis alone doesn’t satisfy me,” something that observers had correctly inferred for years.

Still, in the slightly more other-centered game of doubles, Shriver proved to have every bit of the killer instinct necessary to win the biggest titles. Give her a healthy player-coach relationship and a functional right shoulder, and I suspect her killer instinct would’ve been sufficient on the singles court, as well.