In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Ashley Cooper [AUS]Born: 15 September 1936

Died: 22 May 2020

Career: 1952-63

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1957, 1958)

Peak Elo rating: 2,164 (1st, 1958)

Major singles titles: 4

Total singles titles: 31

* * *

Ashley Cooper must be the only player in tennis history to take over the #1 spot in the world rankings after losing a lopsided major final to the previous #1.

Cooper was the clear number two headed into the 1957 Championships at Wimbledon. The 20-year-old from Melbourne had taken a giant step forward by winning the Australian national title that year. But Wimbledon defending champion Lew Hoad was clearly head-and-shoulders above the field, and he was rounding back into form after back problems hampered him earlier in the season. Aside from Aussie tennis honcho Sir Norman Brookes, a Cooper partisan, everyone favored Hoad. Both men raced to the final, losing only one set apiece in the first six rounds.

Hoad played one of the best matches of his life for the title. One out of three points ended in a Hoad winner, and Cooper managed only five games. It was over in 57 minutes. Even Sir Norman had to admit that Lew was king.

Within a week, the newly-minted champion signed on with Jack Kramer to play in the professional ranks. He agreed to a two-year deal worth $125,000, leaving the amateur game behind.

Hoad’s defection left amateur tennis without its top dog. In the days before ATP computer rankings, tournaments relied on the annual rankings published by veteran sportswriters such as Lance Tingay of The Daily Telegraph. Ashley Cooper, the inexperienced Wimbledon runner-up who occupied second place on the previous list, became the default #1 and would take his place at the top of the draw two months later at the US National Championships.

* * *

It’s easy to forget about Ashley Cooper amid the onslaught of Australian talent in the 1950s and 1960s. From 1952 to 1973, the span that Rod Laver dubs the Golden Era of Australian tennis, Aussies won 58 of 88 major men’s singles championships. 40 of the finals were decided between Australians. 62 of the men’s doubles titles went to the same nation, and the lads from down under held the Davis Cup for all but three years between 1950 and 1967.

If there was a platinum generation at the height of the Golden Era, Cooper was smack in the middle of it. Born in 1936, he was two years younger than Hoad and Ken Rosewall. He was two months older than Roy Emerson, and two years older than Laver and Fred Stolle. Had Hoad and Rosewall hung on a bit longer in the amateur ranks, Cooper may never have even earned a spot on the Davis Cup squad.

The lure of pro tennis paychecks in the 1950s ensured that no one dominated the majors for long. Tony Trabert won three-quarters of the grand slam in 1955, then went professional. Rosewall switched allegiances after taking the 1956 title at Forest Hills. Hoad accepted a record-setting bonus after crushing Cooper at Wimbledon in 1957. Those men–plus Richard “Pancho” González, Frank Sedgman, and Pancho Segura, among others–were playing elite-level tennis in 1958, just not at the grand slam events. They barnstormed around the world and contested separate pro tournaments. The amateur circuit–including the majors–was left to a mix of promising youngsters and veterans committed to the amateur game.

The fluctuations at the top of the rankings were perfectly suited to the tennis factory that was Oz. When Cooper and his peers learned the game, Australia didn’t face the same post-World War II austerity that hampered Europe. Aussies didn’t view tennis as an upper-class pursuit, like many Americans did. The country was tennis-mad, and Harry Hopman–together with a large cast of coaches, former players, and regional talent scouts–groomed the best youngsters for international glory.

The deep pool of Australian talent was never more evident than in 1957. Seven different men reached a grand slam semi-final that year, five of them Aussies. In the first major without Hoad, at Forest Hills, Cooper reached the final without the loss of a set. The championship match pitted him against unseeded Queenslander Mal Anderson. Cooper had won all six prior meetings with Anderson, including the 1957 Australian Open semi-final, but the underdog was too strong, winning 10-8, 7-5, 6-4. Both men impressed the crowd: No less an authority than Don Budge was driven to exclaim, “Wow, these guys can play!”

Cooper remained #1 at the end of the year, with one title, two finals, and a semi-final showing at the majors. He would dispel any lingering doubts–and play his way into the Hall of Fame–in 1958.

* * *

Ashley Cooper didn’t quite fit the mold of the Golden Era star from down under. Like most of his peers, he came from a middle-class background. But both of his parents were teachers, and they valued education. Harry Hopman encouraged his charges to leave school in their mid-teens–many Australian boys did so anyway–and take low-level jobs with sporting goods firms. The positions were essentially sponsorships that allowed budding talents to travel the country playing exhibitions, and they offered ample time off to compete at tournaments.

Cooper not only finished high school, he earned a scholarship to a teaching college. His father didn’t want tennis to derail his education, so he gave Ashley a year or two–maximum–to see what he could accomplish in the sport.

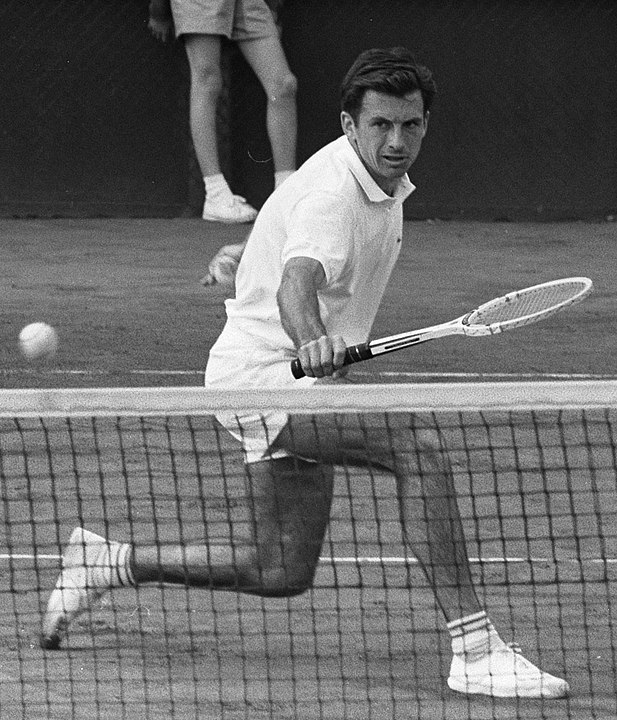

Cooper before his first match at Wimbledon in 1958

Cooper now had a deadline, and he trained like it. Hopman was known for his demanding practice regimen, putting his athletes through hefty doses of running and two-on-one drills that left foreign players in awe. Cooper was the one player who felt the need to do even more.

Teammates called him “six-pack”–a moniker that would’ve fit the drinking habits of most Australian players, but referred instead to Cooper’s physique. The New York Times called him a “fanatic for physical condition,” noting that his first stop after winning Wimbledon and crossing the Atlantic in 1958 was the New York Athletic Club. On exhibition tours, he would ask the driver to stop 10 kilometers from his destination. He’d run the rest of the way.

As Cooper said, “When a Hopman player walked onto the court, he would be fit and strong and able to outlast anyone he played.” Ashley could outlast even another Hopmanite. He won 28 of his 37 career five-setters as an amateur, 10 of the marathon victories coming against fellow Aussies. He played 11 five-setters in his banner year of 1958, and he won 10 of them.

* * *

Ashley Cooper was nearly unstoppable in 1958. A right-handed serve-and-volleyer, he was steady if not spectacular, with no world-class shots but no glaring weaknesses. His even temper complemented his unparalleled fitness. He began his career year by winning every match he played down under, defeating Mal Anderson in straight sets to defend his Australian national title. His first stop abroad was Roland Garros, where he reached the semi-finals for the third year running, losing a heartbreaker to Luis Ayala after winning the first two sets. It was his only five-set loss of the season, and it would come back to haunt him.

At the time, though, the early exit at the French was little more than a stumble. Cooper made a smooth transition to grass, winning his first seven sets at the North of England Championships before battling his countryman, Roland Garros champ Mervyn Rose, to a 4-6, 7-5, 10-12, 6-1, 14-12 victory in the final. He withdrew after one round at Queen’s Club, and taking the extra rest would prove wise.

All of Cooper’s extra time in the gym paid off at Wimbledon. In seven matches, he played 28 sets, spanning 322 games. It’s an all-time record for a champion, and one that is unlikely to be broken in the tiebreak era. Abe Segal made him work to the tune of 13-11, 6-3, 3-6, 14-12 in the fourth round, Bobby Wilson put him through another five sets in the quarters, and Mervyn Rose won a 9-7 first set in the semi-finals. Another outstanding Australian, Neale Fraser, didn’t look like much of a threat in the final, but ultimately pushed Cooper to 11-11 in the fourth set before the iron man claimed his title, 3-6, 6-3, 6-4, 13-11.

The US Nationals were easier going, but a second straight major was far from a sure thing. Back pain contributed to an early loss for Cooper at the Eastern Grass Court Championships, and Mal Anderson beat him in the final at Newport. At Forest Hills, none of that turned out to matter. Cooper reached the title match with the loss of only a single set, waltzing past Ayala in the second round and Fraser in the semis.

Anderson nearly defended his 1957 title, serving for the match at 5-4 in the fourth set. Cooper summoned his best backhand returns, rifling Mal’s “whiplash” serves back at Anderson’s feet to break to love. Cooper won the set, but 18 games later, the match once again appeared to be Mal’s. At 6-5 in the decider, Cooper lost his footing, and for several minutes he was unable to stand, clutching his ankle in pain. After receiving treatment, he somehow recovered and took the match, 6-2, 3-6, 4-6, 10-8, 8-6.

There was no question that Cooper would once again stand as the #1 amateur in the world rankings. 60 years later, he would rue the loss in Paris as “the one that got away.” Missing out on the French title–and the calendar-year grand slam–certainly deprived him of a more prominent place in the history books. But he had little else to regret. Cooper won three of the four majors, plus another 11 titles, for a cumulative record of 81 wins against 7 losses. The only unknown was whether this new, improved Ashley Cooper was the equal of Lew Hoad and his fellow professionals.

* * *

For all of its triumphs, Cooper’s 1958 season ended in disappointment. Australia held the Davis Cup after winning the international competition for two years running, and they hosted the United States in the year-end Challenge Round to determine whether the trophy would extend its stay in Oz. Cooper and Anderson were picked to play the singles. The star of the tie, however, turned out to be the 22-year-old Peruvian-American Alex Olmedo, who beat both Aussies in singles. Olmedo completed his rampage by partnering Ham Richardson to defeat Anderson and Fraser in a doubles rubber for the ages, 10-12, 3-6, 16-14, 6-3, 7-5.

Cooper can hardly be blamed for losing to Olmedo, who would win the Australian Championships the following month and Wimbledon–over a young Rod Laver–later in 1959. But there were plenty of excuses. Cooper had just married Helen Wood, Miss Australia, an event that put him squarely in the public eye. Australia loved their tennis stars, but Helen was the real celebrity, and Cooper joked that for years after, he would be “Mr. Wood.”

Just as much on Cooper’s mind was his intent to go pro. Like Rosewall and Hoad before him, Ashley couldn’t resist a real paycheck after years of traveling cheap as a federation-sponsored tennis bum. He was so distraught at the loss of the Davis Cup that he considered canceling the pro contract to help win back the trophy in 1959. But ultimately, he wanted to test himself against players like Hoad and González.

He was right to wonder where he stood. Years later in his autobiography, pro tennis promoter Jack Kramer asked, “Who would you rather see play? Cooper versus Anderson for the championship of Australia, or Hoad versus [González] for the championship of the world?” If González was the prototypical professional champion without much of an amateur record, Ashley Cooper was the opposite. The man who dominated amateur tennis for 18 months had lasted less than an hour against Hoad in Lew’s last match at Wimbledon.

After 7 matches, 28 sets, and 322 games,

at Wimbledon in 1958

The pundits proved correct. Cooper was out of his depth as a pro. In 1959, he scored wins over González, Hoad, and Tony Trabert, but these were few and far between. On a North American tour that year with González, Hoad, and Mal Anderson, he placed third. He won about one-third of the time, often playing the undercard match against Anderson.

He wasn’t the first player to have a hard time transitioning to the professional lifestyle, which often felt more like a traveling circus than the laid-back, clubby atmosphere of amateur tennis. Cooper never fully established whether he could’ve become a contender on the pro tour. An arm injury in 1962 left him immobilized for months, and at age 27, his career was over.

* * *

The Australian dynasty, of course, continued. Olmedo and Nicola Pietrangeli managed to sneak off with the next three majors, before Neale Fraser got things back on track with the 1959 title at Forest Hills. Fraser and Rod Laver combined for three-quarters of the grand slam in 1960, and Roy Emerson won the first two of his twelve in 1961. The trio of Fraser, Laver, and Emerson won back the Davis Cup in 1959 and held it for four years.

It’s impossible to settle the question of how Cooper compared to the best of the pros at his peak. My Elo ratings make an attempt, but any mathematical approach is limited by the fact that the two groups of top players never mixed, with only one or two players switching sides each year–and always moving in the same direction.

Still, it’s worth considering what the algorithm has to say. Elo concludes that Cooper was in fact the best player in the world at the end of both 1957 and 1958. In 1957, he finished the season with a minor edge over both Mal Anderson and Ken Rosewall, and a slightly larger lead over Richard González and Lew Hoad. While that order is bit hard to swallow, at least it’s based on ample data: Rosewall played over 200 matches that year, and Hoad topped 120.

Cooper is the Elo #1 again at the end of 1958, after his 81-7 season in the amateur ranks. His year-end rating of 2,145 ranks 10th for the entire 1950s, behind only the strongest seasons of González, Hoad, Rosewall, Jack Kramer, Frank Sedgman, and Jaroslav Drobny. Elo gives him a wide lead over #2 Rosewall, who is followed by amateur Mervyn Rose, and then González and Anderson.

Maybe Cooper would’ve eventually figured out the pro game. Either way, the circuits were different enough that they can’t be compared directly. Cooper’s brief career leaves him far behind the likes of González, Hoad, and Rosewall in lists like these. But for that one short span, Ashley Cooper proved that he deserved the #1 ranking he first inherited under such odd circumstances. One of a long line of Golden Era stars from down under, Cooper delivered a 1958 season that ranks among the very best an Australian ever assembled.