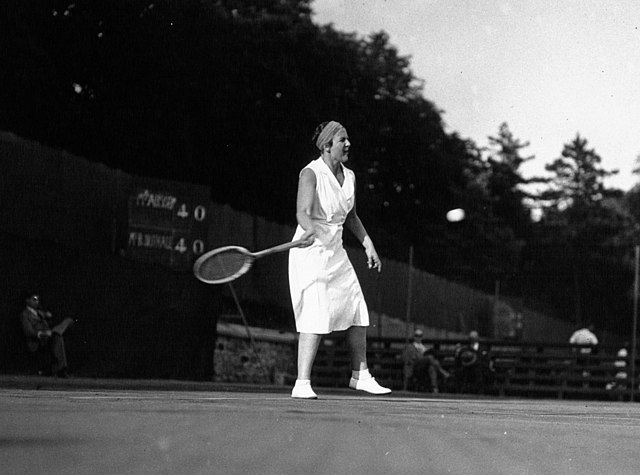

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Betty Nuthall [GBR]Born: 23 May 1911

Died: 8 November 1983

Career: 1924-46

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 4 (1929)

Peak Elo rating: 2,035 (2nd place, 1931)

Major singles titles: 1 (1930 US Nationals)

Total singles titles: 16

* * *

Women’s tennis history is chock-full of stars who relied on powerful groundstrokes to overcome the handicap of mediocre serving. The young Betty Nuthall took this contrast to its extreme, yet reached a major final only a few months after her 16th birthday.

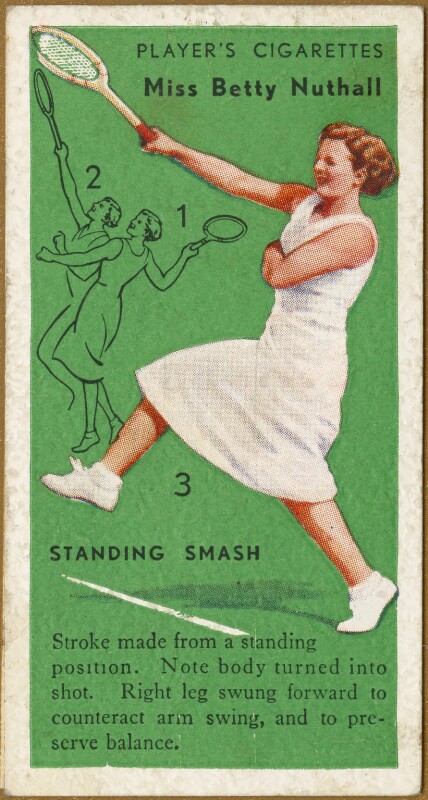

Nuthall was the last top-ranked woman to serve underarm. When she began playing juniors and adult events around England in the 1920s, older spectators could remember seeing underarm serves, but the style was already long out of fashion. Somehow, it worked. Betty’s 19th-century service was enough for the 15-year-old to win a Wightman Cup match against an up-and-coming Helen Jacobs, reach the quarter-finals at Wimbledon, and earn a place opposite Helen Wills in the title match of the 1927 US National Championships.

The word “underarm” doesn’t quite do justice to Nuthall’s technique. After the Jacobs win, the New York Times tried to describe the serve: “She stands about fifteen feet behind the service line, cuts the ball and just about gets it into play. It makes it hopeless for her to think of getting to the net.” The reporter exaggerated a bit. Jacobs described Betty’s service position as “several” feet back of the line.

You can see her serve at 1:22 in this video clip. She’s not far back of the line, and the stroke is more like the sort of forehand you’d hit to start a warm-up rally, instead of the deceptive, drop serve used by occasional underarm servers today. It’s actually not that different from the underarm delivery used by Aryna Sabalenka when she couldn’t land her second serves in Adelaide last month.

Whatever her exact position, she immediately switched to offense once the ball was in play. Bill Tilden watched the newcomer on her first US tour, and while he found her game “crude,” he’d never seen a woman hit a harder forehand.

This was high praise in the era of super-slugger Helen Wills. Nuthall didn’t fare well against Wills in the Forest Hills final, dropping the first set in 12 minutes and losing the match, 6-1, 6-4. But she was an extreme underdog, so onlookers tended to emphasize the positive. It was the hardest hitting–from both sides of the net–ever seen in the US National Championships. The Times described Nuthall’s signature shot as an “annihilating forehand,” and the paper of record offered what it probably considered to be the highest praise of women athletes in the 1920s: Play was “maintained at so furious a tempo as to make even most men’s tennis seem tame by comparison”

* * *

Betty Nuthall’s surprise New York run in 1927 endeared her–a Brit–to American fans, and she would return to Forest Hills six more times. More importantly, the clash with Helen Wills gave Betty a stick with which to measure her career. She didn’t come close to an upset, but once she got into the match and began to vary her game, she wasn’t wiped off the court, either.

It wasn’t an easy time to be an elite woman not named Helen Wills. Between 1927 and the final of the 1933 US Nationals, Wills didn’t lose a single match. By the time she first faced Nuthall in August 1927, she had won 36 consecutive sets, and wouldn’t drop another one for more than half a decade.* She accomplished that against the best amateur competition, albeit over a limited schedule.

* !?!?!

Nuthall’s peak almost exactly lines up with the reign of Queen Helen. But no one seems to have told Betty that the American was unbeatable.

Two years later, Nuthall and Wills met in the Wightman Cup, the annual team competition between picked squads of Americans and Brits. Betty met Helen Jacobs on the first day of the competition. Armed with a new, solid overhead service that cost her most of the 1928 season to develop, Nuthall came within a whisker of victory, losing 7-5, 8-6. Wills awaited on day two. Against the elder Helen, Nuthall did even better, losing 8-6, 8-6. Only Simonne Mathieu had come so close to taking a set from the queen in the last two years.

The American press was once again in awe of the plucky Brit: “Miss Wills’s large number of errors testifies to the troubles she had in handling Miss Nuthall’s strokes, but one would have had to be present at Forest Hills to appreciate the daring and guile with which the English girl deployed them. Her use of the drop shot was the most masterly demonstration of this stroke that has been seen in a woman’s match in this country since Miss Elizabeth Ryan defeated Miss Wills with the same weapon at Seabright in 1925 and 1926.”

The following year, Nuthall won the US National Championships, her only major title in singles. Jacobs was injured and Wills opted not to play. Betty was thrilled, but an interview with her mother revealed a sore spot. Betty was more interested in a rematch with Queen Helen than a title at Forest Hills.

* * *

It would be reasonable to assume that a player capable of holding her own with Helen Wills would find the rest of the field to be easy pickings. Alas, it was not so for Betty Nuthall. In the official rankings of the time, Betty topped out at 4th in the world. My Elo ratings are a bit more generous, putting her at 2nd after the Forest Hills title in 1930, and 3rd after the 1931 season. Whichever authority you prefer, she only ranked in the year-end top-ten on five occasions.

She never reached the semi-finals in 13 tries at Wimbledon. She had a career losing record in finals, despite the majority of those matches coming on home soil and most of them against British competition that would struggle to win more than a game or two against Wills.

Helen Jacobs devoted a chapter to Nuthall in her 1949 book, Gallery of Champions. She traced Betty’s limitations back to her success as a child prodigy. Nuthall’s father put a racket in her hand at age seven–quite early for the era–and she was playing tournaments two years later. She was the English girls’ champion at 13, and she won her first adult event the same year.

Nuthall (right) with Helen Jacobs

As Jacobs saw it, Betty was a tactician, not a strategist. She developed her game (including that old-fashioned serve) long before her physical peak. Like many dominant juniors, she failed to make adjustments when faced with tougher competition. The resulting losses then had an out-of-proportion effect on her confidence.

* * *

Maybe Betty Nuthall just played better across the Atlantic, away from the British fans who had expected great things from her based on the performances of a pre-teen. Certainly she had her share of fans in the States–she was popular enough to merit a screen test in Hollywood. After losing badly to Helen Wills in the 1931 Wightman Cup and stumbling through a shortened 1932 season without a title, Betty had one more great run in store for her American fans.

A middling English season for Nuthall in 1933 ended with a fourth-round exit to Peggy Scriven at Wimbledon. A month later, she raced to the title at the Forest Hills warm-up in East Hampton, beating 19-year-old phenom Alice Marble in the final. Marble had won 33 of 35 matches that season before Nuthall stopped her. The young Californian was already famous for her best-in-class American twist serve. It didn’t bother Betty one bit.

Nuthall carried her momentum through a Wightman Cup victory over Carolin Babcock, then met Marble again in the quarter-finals of the US Nationals. The winner would meet Helen Wills, and perhaps it was the promise of that matchup that gave Betty the push she needed to pull off one of the greatest comebacks in the history of the event.

Marble won a tight first set, 8-6, then Nuthall quickly evened it up with a 6-0 second. The contest swung back the other way in the third, as Marble built a 5-1 lead, earning two match points at 15-40 on Betty’s serve. Nuthall won four points in a row to survive, but found herself in trouble again on Marble’s serve at 5-4. Betty won the first three points, but the American grabbed the next four in a row. Marble double-faulted away what would be her final match point. Nuthall won the last eight points of the match to seal the final set, 7-5, and earn another shot at Wills.

Queen Helen was far from 100% at the 1933 US Nationals. She was coping with a lingering back injury, and before the semi-final against Nuthall, her doctor recommended that she take six months off. Her back was slow to warm up, which helps explain how Betty took the first set, a 6-2, 12-minute special of the sort that Wills usually dealt out to others.

It was the first set Wills had lost at Forest Hills since 1925, and only the second she’d conceded anywhere since 1927.* Hobbled or not, she found her form and bounced back to 6-3 and 6-2 victories in the final two sets. Helen’s back injury would become one of the most controversial ailments in the game’s history after she retired in the middle of the third set to Helen Jacobs in the final. But by then, Nuthall’s tournament–and her run near the top of the sport–was over.

* Everyone was a bit off their game that day. Wills served two games in a row in the second set. Neither player, nor any of the 13 officials on court, recognized the error.

In 1934, Betty lost in the third round at the French Championships and the first round at Wimbledon, to long-time nemesis Eileen Bennett Fearnley-Whittingstall. She once again made the trip across the Atlantic, entering Forest Hills as the top foreign seed. But she failed to live up to the billing, winning only one match. Her 27-8 season record was padded by early success on British clay courts, and most of her eight losses came against players she would’ve beaten a few years earlier. At 23 years of age, she fell out of the top ten, and she’d never again get close.

Nuthall continued playing tournaments in Britain until World War II, and played more than her share of exhibition matches to support the war effort. She made her final appearance in the Wimbledon singles draw in 1946 and reached the fourth round.

By then, a few more generations of tennis prodigies had come and gone, and plenty of ladies now hit their forehands every bit as hard as Nuthall did. But none of them had held their own against Helen Wills.