Also today: Wild cards and doping bans; Miami preview podcast

It is not easy to analyze the drop shot. Players don’t hit it very often, they sometimes hit it from very favorable or very unfavorable circumstances, and the goal of the shot sometimes extends beyond winning the point at hand. We can point to someone who hits droppers well and seems to win a lot of points doing so, but how much is the skill really worth?

Carlos Alcaraz is the poster boy for the modern drop shot. He loves to hit it–possibly too much–and when he executes, it’s one of the most stunning shots in tennis. At the business end of his Indian Wells campaign last week, he went to the well seven times against Alexander Zverev, ten times against Jannik Sinner, and three more in the final against Daniil Medvedev. He won 11 of those 20 points. That doesn’t sound so impressive, but Alcaraz could hardly complain about the end result.

To get a grip on drop shot numbers, we have a lot of work to do. What is a good winning percentage? Do any players suffer because they hit the drop shot too much? Is there a lingering effect from disrupting your opponent’s balance? Finally, once we have a better idea of all that, how does Alcaraz stack up?

Drop shot basics

To keep the data as clean as possible, let’s be specific about which strokes we’re looking at. While one can hit a drop shot in response to another drop shot (a “re-drop”), and it’s possible to hit a drop shot from the net in reply to a short volley or half-volley, those aren’t typically what we’re referring to. There are probably players (starting with Alcaraz!) who are better at that sort of thing than their peers, but those low-percentage recoveries aren’t today’s focus.

In this post, when I say “drop shot,” I mean a drop shot from the baseline, excluding all shots from the net, including responses to earlier drops.

The Match Charting Project gives us over 4,600 men’s matches to work with since 2015. Those 750,000 points include almost 35,000 drop shots. That works out to a drop shot in about 4.6% of points. Or from the perspective of a single player, it’s 2.3%, 1 out of every 44 points. The player who hits the drop shot ends the point immediately (via winner or forced error) about one-third of the time, and 19% of the droppers miss for unforced errors. Overall, the player who hits the drop shot wins the point 53.8% of the time.

From the 60 players with the most charted points to analyze, here are the 15 who win the highest percentage of points behind their drop shots:

Player Drop Point W% Kei Nishikori 69.6% Richard Gasquet 66.2% Nicolas Jarry 65.3% Sebastian Baez 63.2% Carlos Alcaraz 62.1% Rafael Nadal 61.3% Lucas Pouille 60.3% Roger Federer 59.7% Alejandro Davidovich Fokina 59.3% Roberto Bautista Agut 58.9% Marton Fucsovics 58.2% Pablo Carreno Busta 58.1% Jannik Sinner 57.7% Dominic Thiem 57.5% Andy Murray 56.7%

Alcaraz does well here! Despite the presence of Kei Nishikori at the top, the list is heavily skewed toward clay-courters. Drop shots are a more central tactic on clay than on other surfaces, which works in both directions: Clay-courters are more likely to develop good drop shots, and players who have dangerous droppers are more likely to succeed on dirt.

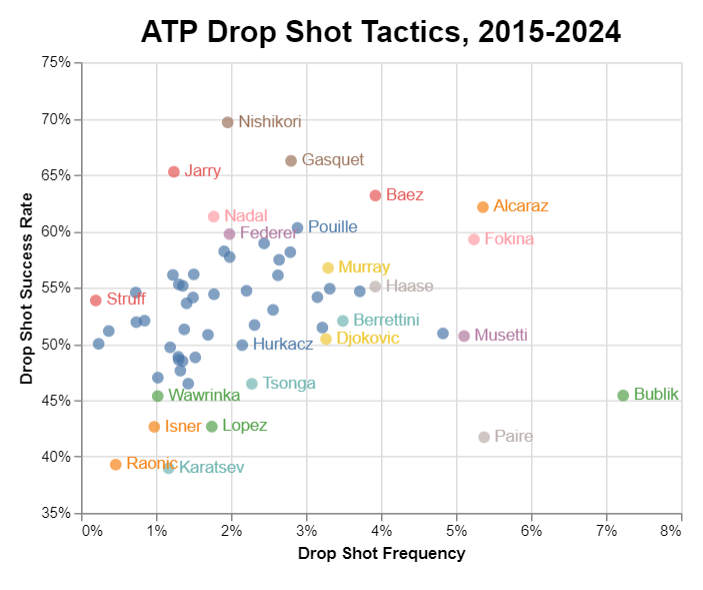

Another skill that contributes to a spot on the list is good judgment. Nicolas Jarry doesn’t hit many drop shots, so he is probably picking the ripest opportunities when he does. There’s almost zero correlation between frequency of drop shots and drop shot success rate. Call it the Bublik Rule. From the same group of 60 tour regulars, here are the top 15 ranked by frequency:

Player Drop/Pt Drop Point W% Alexander Bublik 7.2% 45.4% Benoit Paire 5.4% 41.7% Carlos Alcaraz 5.4% 62.1% Alejandro Davidovich Fokina 5.2% 59.3% Lorenzo Musetti 5.1% 50.7% Holger Rune 4.8% 50.9% Sebastian Baez 3.9% 63.2% Robin Haase 3.9% 55.1% Fabio Fognini 3.7% 54.7% Matteo Berrettini 3.5% 52.0% Nick Kyrgios 3.3% 54.9% Andy Murray 3.3% 56.7% Novak Djokovic 3.3% 50.4% Botic van de Zandschulp 3.2% 51.4% Frances Tiafoe 3.2% 54.1%

Bublik may be turning things around: In the Montpellier final last month, he attempted 18 droppers and won the point 14 times. For a consistent high-frequency, high-success combination, though, we’re back to Alcaraz. Only Carlos, Alejandro Davidovich Fokina, Sebastian Baez, and Andy Murray (barely) appear on both lists.

Here are all 60 players in graph form. The top right corner shows players who hit a lot of drop shots and win most of those points. The closer to the bottom, the lower a player’s success rate; the closer to the left, the fewer droppers he attempts:

As a percentage of all points played, Bublik wins the most behind his drop shot. But it comes at a cost, since he hits so many of them, often sacrificing points because of it. If we assume that each drop shot is struck from a precisely neutral rally position, meaning that the would-be dropshotter has a 50% chance of winning the point, Bublik is losing points by going to the drop shot so often.

That’s a big assumption, and it probably isn’t exactly true for Bublik, or for anyone else. But if we stick with that for a moment, we can combine frequency and success rate into one number. Take the difference between success rate and 50% (that is, the gain or loss by opting for a drop shot), multiply that by frequency, and you get the percent of total points that the player wins by choosing the drop. The resulting numbers are small, so here’s the top ten (and bottom five) list showing points gained or lost per thousand:

Player Drop Pts/1000 Carlos Alcaraz 6.5 Sebastian Baez 5.2 Alejandro Davidovich Fokina 4.9 Richard Gasquet 4.5 Kei Nishikori 3.8 Lucas Pouille 3.0 Pablo Carreno Busta 2.3 Andy Murray 2.2 Roberto Bautista Agut 2.2 Rafael Nadal 2.0 … Jo Wilfried Tsonga -0.8 Feliciano Lopez -1.3 Aslan Karatsev -1.3 Alexander Bublik -3.3 Benoit Paire -4.5

Reduced to one number, Alcaraz is our dropshot champion. Six points per thousand doesn’t sound like a lot, but to invoke the familiar refrain, the margins in tennis are small. Beyond the top five or ten players in the world, one single point per thousand is worth one place on the official ranking list. Stars of Alcaraz’s caliber are separated by wider gaps, but it’s still a useful way to gain some intuition about the impact of these apparently miniscule differences.

The after-effect

In the hands of someone like Carlitos, the drop shot is a reliable way to win points. But the impact can go further than that. All sorts of tactics–drop shots, underarm serves, serve-and-volley–can theoretically be justified by some longer-term effect. If your opponent is camped out six feet behind the baseline and you want him somewhere else, a drop shot will surely give him something to think about.

This is hard to quantify, to put it mildly. How long does the effect of a drop shot last? Does it decay after each successive point? Does it disappear at the end of a game? On the next changeover? Ever? Jarry might need to hit the occasional drop shot to remind his opponent that he can do it, but Alcaraz doesn’t even need to do that. Everybody knows he’ll dropshot them, so he’s probably in his opponent’s head even before he hits the first drop shot of a match.

The evidence is unclear. About two-thirds of drop shots are hit by the server. I looked at the results of points immediately after a point with a drop shot, points two points later, and all the points that followed within the same game. When the server hits the drop shot, his win percentage on those subsequent points is worse than his win percentage on other points throughout the match–that is, non-dropshot points that didn’t follow so closely after he played a dropper:

Situation Win% Next point 63.3% Two points later 62.6% Same game 62.5% All others 64.2%

I suspect that the dropshot effect (if there is one) is swamped by all the other influences at work here. Droppers typically occur in longer rallies, which might tire the server. The server might go for a drop shot when he runs out of ideas, another thing that might go through his mind as he prepares for the next point. This seems to work against Alcaraz more than other servers:

Situation Win% Next point 62.0% Two points later 62.1% Same game 63.2% All others 65.0%

The same pro-returner bias appears when we look at the results when it is the returner who goes for the drop shot. After seeing the numbers above, it’s tough to say that hitting a drop shot causes the higher success rate on subsequent points, but it is nonetheless a striking effect, especially for Carlitos:

Situation Alcaraz W% Tour W% Next point 44.0% 38.3% Two points later 41.8% 37.6% Same game 41.5% 37.9% All others 40.1% 35.8%

Whatever the mechanism here, it goes beyond “drop shot good, opponent confused.” More research is needed, and camera-tracking data would help.

Regardless of the after-effects (or lack thereof), the stats support the common contention that Alcaraz possesses a world-class drop shot. He might use it too often in some matches, and certainly there are individual situations in which he should have done something else. In the aggregate, though, the tactic is working for him. It produces more value than any other player’s dropper has done in the last decade. Tennis analytics is hard, but goggling at the game of Carlos Alcaraz is easy.

* * *

Wild cards and doping suspensions

Simona Halep returned to action this week, thanks to a Miami wild card granted immediately after her doping suspension was reduced. Halep is well-liked, and there were few objections to her appearance in the draw. But Caroline Wozniacki, while careful to say she wasn’t specifically targeting Halep, said that she was against dopers getting post-suspension wild cards.

We’ve done this before. In 2017, Maria Sharapova returned from 15-month ban and immediately got a wild card to enter Stuttgart. The tennis world spent a few weeks in a dither about whether she’d get one to the French Open, too. She didn’t.

I wrote about the Sharapova situation at the time. I argued that Sharapova ought to get those opportunities. The reason I gave at the time was that it was better for the sport: She was one of the best players in the game, and fields would be more competitive with her than without her. Another reason is that without wild cards, it’s a long road back. Unranked after more than a year on the sidelines, a player needs to enter qualifying at ITFs, wait two weeks for those points to go on the official rankings (assuming they win!), and then use those rankings to enter (slightly) stronger events, with entry deadlines several weeks in advance of the tournaments themselves.

Climbing back up the ladder can take months. Is that part of the penalty? Is a 15-month suspension supposed to be 15 months of no competition, followed by 3-6 months of artificially weak, poorly remunerated competition? In team sports, this isn’t an issue, because coaches can put returning players in the lineup as soon as they’re ready.

As usual, the problem is that tennis doesn’t have unified governance. None of the various bodies in charge have an applicable policy. Sharapova was fine, and Halep will be fine, because stars get wild cards (if not as many as they would like), while lower-ranked players are stuck heading to Antalya to rack up ITF points. The discrepancy is particularly glaring in a case like that of Tara Moore, who missed 19 months but has been fully exonerated.

The WTA is apparently considering granting special rankings to players who have been cleared of doping charges or had their bans reduced, essentially treating them as if they are returning from injury. That’s better than nothing, but it wouldn’t address the more common scenario illustrated by Sharapova’s return.

I would go further and grant special rankings to any player returning from suspension. The term of the suspension is the penalty, period. Even better, and fairer to the field as a whole: Grant those special rankings in combination with a policy that restricts wild cards. For instance, Halep could have eight or ten entries into tournaments on the basis of her pre-suspension ranking, but no wild cards for her first year back. That way, individual tournament directors don’t need to re-litigate each doping ban, players have a predictable path to follow post-suspension, and superstars aren’t given any special advantages.

* * *

Miami preview podcast

I had a fun conversation yesterday with Alex Gruskin, talking about my recent Iga Swiatek piece and previewing the men’s and women’s draws in Miami. Click here to listen.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email:

This is really interesting.

Does winning a drop shot point in your calculation only points where the drop shop ended the rally? I ask because — isn’t it the case that players often hit the drop shot, forcing opponent to pop it up, followed by a volley winner after?

e.g.

Shot 1: Drop shot

Shot 2: Barely gets racket on it

Shot 3: Volley winner

Are such points included in your analysis? Or does it have to be an outright drop shot winner.

all the win rates in this post are *point* win percentage, so it includes any number of shots after the drop shot. 60-70% of points won with (or after) a drop shot are won with the drop shot itself (winner or immediate forced error); the other 30-40% take longer

Hi Jeff et all

INteresting stuff!! Really.

But subscribing to your site is technically not ok. 404 etc.

Keep up the good work

Arnold

Great article, as always Jeff.

What about a player’s style of drop shots that they use? In other words, I feel Djokovic only uses his drop shot on the back-hand side and up the line, at least later in his career.

Also, I noticed that a lot of times, amid a long rally, you’ll see a player run out of ideas and just use the dropper as a bailout shot- if it works, great, and if not, then OK.

yep, dropshots are definitely not all created equal. you probably in the follow-up bublik piece I broke down fh/bh. worth looking in the future at what angles/situations work best, though for any given player, there probably isn’t enough data to come to solid conclusions.