Also today: Upsets, (partly) explained; January 23, 1924

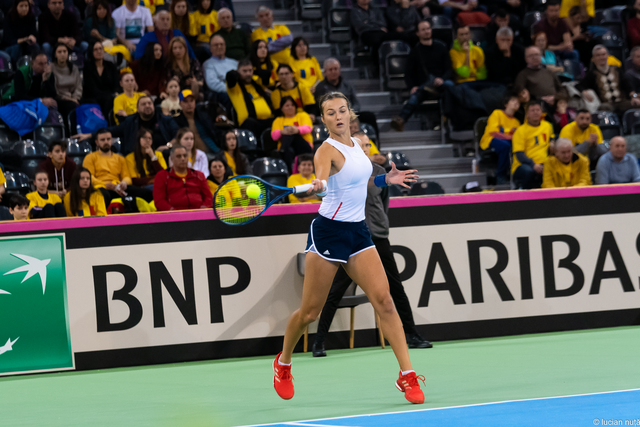

Should we have seen this coming? Of all the surprises in the top half of the 2024 Australian Open women’s draw, Anna Kalinskaya’s run to the quarter-finals stands as one of the biggest. The 25-year-old was ranked 75th entering the tournament, and she had never reached the third round of a major in 13 previous main-draw attempts.

Had we looked closely before the tournament, we wouldn’t have found a title contender, exactly, but we would have identified Kalinskaya as about as dangerous as a 75th-ranked player could possibly be. She finished 2023 on a 9-1 run, reaching the final at the WTA 125 in Tampico, then winning the title at the Midland 125, where she knocked out the up-and-coming Alycia Parks in the semi-finals. 2024 started well, too: The Russian upset top-tenner Barbora Krejcikova in Adelaide, then almost knocked out Daria Kasatkina in a two hour, 51-minute match two days later.

The only reason her official ranking is so low is that she missed nearly four months last summer to a leg injury that she picked up in the third round in Rome. Her two match wins at the Foro Italico pushed her up to 53rd in the world, just short of her career-best 51st, set in 2022. The Elo algorithm, which measures the quality of her wins rather than the number of tournaments she was healthy enough to play, reflects both her pre-injury successes and the more recent hot streak. Kalinskaya came to Melbourne as the 31st-ranked woman on the Elo list.

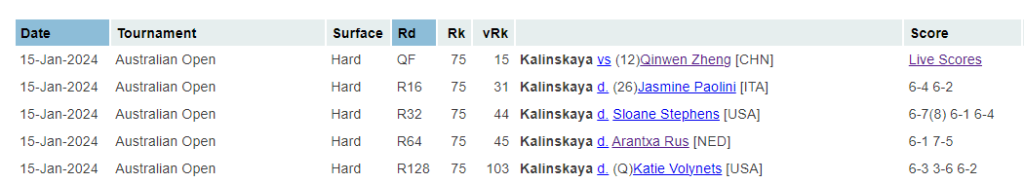

These alternative rankings put a different spin on her path through the Australian Open draw so far. Here are the results from her first four rounds, in which she appeared to be the underdog three times:

Elo has some adjustments to make:

Round Opponent Elo Rk Elo vRk R16 Paolini 31 37 R32 Stephens 31 50 R64 Rus 31 107 R128 Volynets 31 139

Kalinskaya was hardly an early favorite–Stephens did her the favor of taking out Kasatkina, and Anna Blinkova (who lost to Paolini) eliminated the third-seeded Elena Rybakina. But given how the draw worked out, seeing the Russian’s name in the quarter-finals wasn’t so unlikely after all.

More luck

Kalinskaya has a dangerous forehand and a solid backhand, but she isn’t an aggressive player by the standards of today’s circuit. Her 14 matches logged by the Match Charting Project average 4.2 strokes per point, and that skews low because it includes three meetings with Aryna Sabalenka. Yesterday’s fourth-round match against Paolini took 5.3 strokes per point, and the third-rounder with Stephens was similar.

By Aggression Score, the 25-year-old rates modestly below average, at -17 in rallies and -15 on returns. While she doesn’t have any weaknesses that prevent her from ending points earlier, she’s more comfortable letting the rally develop. When Paolini played along, the results were remarkable: 32 points reached seven shots or more yesterday, and Kalinskaya didn’t end any of them with an unforced error.

The downside of such a game style is that a lot of opponents won’t be so cooperative. Last fall, the Russian lost back-to-back-to-back matches against Ekaterina Alexandrova, Viktoria Hruncakova, and Ashlyn Krueger, three women who opt for big swings and short points. By contrast, consider the Rally Aggression Scores of the quartet Kalinskaya has faced in Melbourne:

Round Opponent AggScore R16 Paolini -5 R32 Stephens -16 R64 Rus -59 R128 Volynets -38

Paolini and Stephens have roughly similar profiles to Kalinskaya’s own; Rus and Volynets are even more conservative.

This isn’t just a convenient narrative: Kalinskaya really is better against more passive players. She has played 118 career tour-level matches against women with at least 20 matches in the charting database. Sort them by Rally Aggression Score and separate them into four equal bins, and the Russian’s preferences become clear:

AggScore Range Match Win% 57 to 175 35.7% 0 to 56 46.4% -27 to -1 50.0% -137 to -27 59.4%

If the whole tour were as patient as she is, the Russian would already be a household name.

Alas, it’s rare to draw four straight players as conservative as the bunch Kalinskaya has faced in Melbourne. And having reached the quarter-finals, her luck has run out. Her next opponent is Qinwen Zheng, who has a career Aggression Score of 27 and upped that number in 2023. It could be worse–fellow quarter-finalists Sabalenka and Dayana Yastremska are triple-digit aggressors–but it is a different sort of challenge than she has faced at the tournament so far.

To win tomorrow, Kalinskaya will need to play as well as she has for the last few months, only a couple of shots earlier in the rally. Otherwise, Zheng will end points on her own terms, and thousands of potential new fans will be convinced that Kalinskaya really is just the 75th best player in the world.

* * *

Why are upsets on the rise?

Only four seeds, and two of the top eight, survived to the Australian Open women’s quarter-finals. Many of the top seeds lost early. This feels like a trend, and it isn’t new.

One plausible explanation is that the field keeps getting stronger. Top-level players now develop all over the world, and coaching and training techniques continue to improve. There are few easy, guaranteed matches, even if Iga Swiatek and Aryna Sabalenka usually(!) make it look that way. I believe this is part of the story.

Another component, I suspect, is the shift in playing styles. I noted a couple of weeks ago when writing about Angelique Kerber is that WTA rally lengths have steadily declined in the last decade. In 2013, the typical point lasted 4.7 strokes; it’s now around 4.3. Shorter points are caused by more risk-taking. Risks don’t always work out, full-power shots go astray, and the better-on-paper player doesn’t always win.

In 2019, I tested a similar theory about men’s results. I split players in four quartiles based on Aggression Score and tallied the upset rate for every pair of player types. When two very aggressive players met, nearly 39% of matches resulted in upsets, compared to 25% when two very passive players met. The true gap isn’t quite that big: given the specific players involved, there should have been a few more upsets among the very aggressive group. But even after adjusting for that, it remained a substantial gap.

It stands to reason that the story would be the same for women. Instead of Aggression Score, I used average rally length. I doubt there’s much difference. I didn’t intend to change gears, I just got halfway through the project before checking what I did the first time.

The most aggressive quartile (1, in the table below) are players who average 3.6 shots per rally or less. The next group (2) ranges from 3.7 to 4.0, then (3) from 4.1 to 4.5, and finally (4) 4.6 strokes and up. The following table shows the frequency of upsets (Upset%) and how the upset rate compares to expectations (U/Exp) for each pair of groups:

Q1 Q2 Upset% U/Exp 1 1 40.7% 1.07 2 1 36.2% 0.99 2 2 35.7% 0.99 3 1 35.1% 0.93 3 2 35.5% 0.97 3 3 40.9% 1.07 4 1 37.6% 1.03 4 2 36.6% 1.02 4 3 34.6% 0.95 4 4 34.7% 0.97

(If you look back to the 2019 study, you’ll notice that I did almost everything “backwards” this time — swapping 1 for 4 as the label for the most aggressive group, and calculating results as favorite winning percentages instead of upsets. Sorry about that.)

Matches between very aggressive players do, in fact, result in more upsets than expected. It’s not an overwhelming result, partly because it’s only 7% more than expected, and partly because matches between third-quartile players–those with average rally lengths between 4.1 and 4.5–are just as unexpectedly unpredictable.

I don’t know what to make of the latter finding. I can’t think of any reasonable cause for that other than chance, which casts some doubt on the top-line result as well.

If the upset rate for matches between very aggressive players is a persistent effect, it would give us more upsets on tour today than we saw a decade ago. An increasing number of players fit the hyper-aggressive mold, so there are more matchups between them. The logic seems sound to me, though it may be the case that other sources of player inconsistency outweigh a woman’s particular risk profile.

* * *

January 23, 1924: Debuts and dropshots

Men’s tennis ruled at the early Australian Championships. The tournament had been held since 1905 (as the “Australasian” Championships), but there was no women’s singles until 1922. On January 23rd, midway through the 1924 edition, the press corps was preoccupied with the severity of Gerald Patterson’s sprained ankle and the question of whether Ian McInnes had been practicing.

James O. Anderson, the 1922 singles champion who would win the 1924 edition as well, introduced what was then–at least to the Melbourne Argus–an on-court novelty:

He has developed a new stroke since he last played in Melbourne, and it has proved successful. On the back of the court he makes a pretence of sending in a hard drive, but with a delicate flick of the wrist he drops the ball just over the net, leaving his opponent helpless 30 feet away.

A veritable proto-Alcaraz, was James O.

For the few fans who weren’t solely focused on Australia’s Davis Cuppers, a superstar was emerging before their eyes. Also on the 23rd, 20-year-old Daphne Akhurst made quick work of Violet Mather, advancing to the semi-finals in her first appearance at the Championships.

Akhurst wouldn’t go any further, unable to withstand the heavy forehand of Esna Boyd in the next round. But it was nonetheless a remarkable debut: She won both the women’s and the mixed doubles titles. The correspondent for the Melbourne Age, recapping the mixed final, could hardly contain his admiration:

Miss Akhurst–an artist to her finger tips–belied her delicate mid-Victorian appearance that suggested that she had slipped out of one of Jane Austen’s books by sifting out cayenne pepper strokes from a never-failing supply.

Daphne and Jack Willard–“who ran for every ball, and continued running after he played the ball”–defeated Boyd and Gar Hone in straight sets.

The pair of championships was a harbinger of things to come. Between 1925 and 1931, Akhurst would win five singles titles (losing only in 1927 when she withdrew), four more in the women’s doubles, and another three mixed. The only thing that could stop her were the customs of the day: She married in 1930 and retired a year later. Tragically, she died from pregnancy complications in 1933, at the age of 29.

Daphne is best known these days as the name on the Australian Open women’s singles trophy. For the next several years, there will be many more Akhurst centennials to celebrate.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: