The Women’s Tennis Association was barely four weeks old, and it had already delivered a blow to the prevailing men-first attitude around the sport.

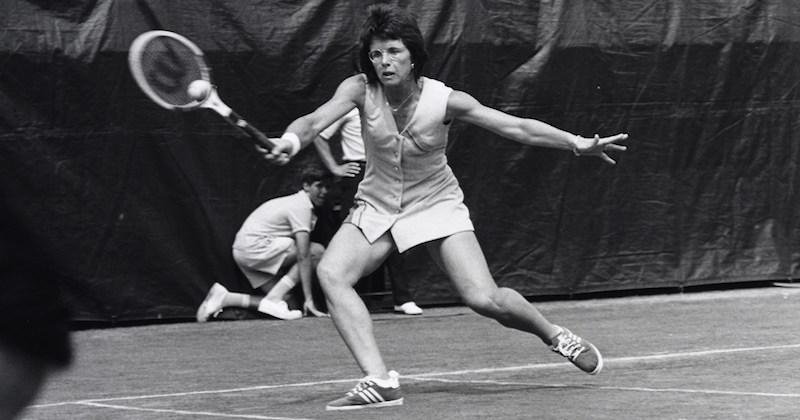

On July 19th, US Open tournament chairman Bill Talbert announced that the 1973 event would be the first-ever major to offer equal prize money to men and women. In 1972, women’s champ Billie Jean King received $10,000 to men’s titlist Ilie Năstase’s $25,000. This year, both winners would get $25,000.

The total prize pot was a record $227,200, and it would be split equally between the genders. Making the difference was a new sponsor, Ban deodorant, which kicked in $55,000. “We feel that the women’s game is equally as exciting and entertaining as the men’s,” said a representative of Bristol-Myers, Ban’s parent company. “We hope that our direct involvement with the 1973 US Open clearly indicates our positive position on behalf of women in sports.”

Talbert agreed. He suggested that the women’s game offered higher-quality rallies, while too many men copied superstar serve-and-volleyers without learning proper groundstrokes to support their attacking game.

If anyone complained about the new reward structure, Talbert said, “I’ll just tell the men to go out and sell their product better.”

First and foremost, the announcement marked an enormous step for King and her WTA brethren. “Thank goodness for Billie Jean King,” said Chris Evert.

Along a different dimension, the Ban “sports grant” signaled how far pro tennis had come in just five years. Gladys Heldman and the initial group of women’s contract pros had recognized from the beginning that female fans and recreational players were an untapped market, and they sold that vision to corporate sponsors like Philip Morris. Talbert was probably right about the quality of the the women’s game, but in another way, it didn’t matter. Ban, and now the US Open itself, understood that prize money was much more than an enticement for top players. Bristol-Myers wasn’t just a purveyor of quality antiperspirants. The company sought to represent a vision of the future.

Jack Kramer, the longtime promoter and now co-founder of the ATP, was slow to learn that lesson. He later wrote that he found another sponsor for the men, as well. To use Talbert’s phrase, the men did sell their product better, thanks to Kramer. But the Open declined the additional money. The tournament decided it was better to offer equal prizes–and align itself with a certain set of values–than to extend the already record sums on offer to half the field.

On this historic occasion, reporters couldn’t help but reach out to Bobby Riggs. The 55-year-old vanquisher of Margaret Court wired back, “I am leaving immediately for Denmark for an operation.” He was talking about a sex change, his chauvinistic way of acknowledging what he had long since figured out: There was an awful lot of money in women’s tennis.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: