Two days before Wimbledon began, 21-year-old Sandy Mayer was still in New Jersey. He reached the finals of the National Collegiate tournament in Princeton, stepping up at the event where, in 1972, he had won the doubles title with Roscoe Tanner. Now he had a chance not only to repeat, but to claim the singles championship–and by so doing, secure team honors for Stanford over a strong challenge from the University of Southern California.

Mayer made it look easy. He breezed past USC’s Raúl Ramírez, 6-3, 6-1, 6-4. He also partnered Jim Delaney to the doubles crown.

Then he got on a plane.

Mayer was the 11th-ranked American, and among the boycott-weakened Wimbledon field of 1973, that made him a marginal contender. He had barely 24 hours to accustom himself to the grass, a tough transition from the en tout cas surface–an ersatz clay not unlike Har-Tru–at the NCAA’s. Fortunately, the draw did him favors. He reached the fourth round by knocking out three straight lucky losers. He lost just one set in the process.

The cakewalk ended in the round of 16, where the collegiate champion lined up against Ilie Năstase. Năstase was the 1972 runner-up, the top seed, and the odds-on favorite to take the title. He had won 53 of his last 54 matches. He was a member of the ATP, the players’ union that organized the Wimbledon walkout. But he was also a captain–nominally, anyway–in the Romanian Army. Orders from Bucharest said he would play. He played.

At his best, Năstase was one of the most gifted players the game has ever seen, a shotmaker who would dig out from impossible positions for the sheer joy of it. Fortunately for Mayer, Ilie on an off-day was decidedly ordinary.

June 30th was one of those days. Tournament organizers expected a blowout, so they put the match on the No. 2 Court. Ilie liked an audience, and the smaller venue was just one of the things working against him. He had stumbled through his first-round match, claiming kidney troubles and skipping a press conference. The ATP boycott had distracted him, as well: He said he had barely thought about tennis for two weeks, even if he did win the Queen’s Club title amid the distraction.

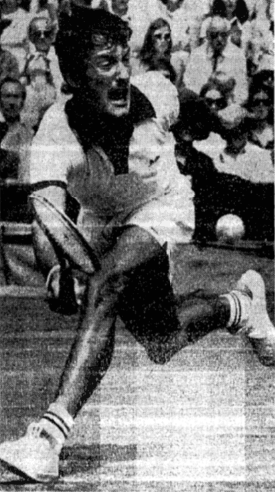

Against Mayer, Năstase “played like an artist whose normal flair was sadly impaired,” according to the Daily Telegraph‘s Lance Tingay. The Romanian lived off his reflexes, but the American was quicker. Mayer–trained literally from the crib by his tennis-coach father–played returns of serve on the rise and kept Năstase off balance. He kicked his own serves wide, taking advantage of the top seed’s deep return position.

Tournament organizers got a brief reprieve when the Romanian, down two sets to love, broke serve to save the third. But the fourth set was back to business. Mayer took it 6-4, breaking in the third game and never looking back.

The NCAA champ had shown signs of brilliance before. He took a set from Stan Smith at the Championships the year before, and he upset Jan Kodeš at the 1972 US Open. But this was something entirely different. Some pundits whispered that Năstase had tanked, that in solidarity with his fellow ATP members, he had lost at the first plausible opportunity. Maybe. Anything was possible where Ilie was concerned.

As for Mayer, he remained an underdog. Kodeš and Jimmy Connors became 7-2 co-favorites, and the Stanford man would take on 8th seed Jürgen Fassbender in the quarters.

He didn’t have to worry about breaking with the union: He was still an amateur. He didn’t know who would get his prize money, except that it wouldn’t be him. At a Wimbledon torn apart by rich men fighting over slices of the pie, the most shocking blow was delivered by an up-and-comer playing for a few bucks a day in expense money.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: