A disappointment for the top men and a disaster for Wimbledon, it smelled like opportunity to Billie Jean King. Five days away from the start of the Championships, a British High Court ruled against Niki Pilić, rejecting his request for an injunction against the All-England Club that would allow him to play. There was vanishingly little hope that the ATP would abandon its boycott of the tournament. Dozens of players–including defending champion Stan Smith and 1971 titlist John Newcombe–had already withdrawn.

Wimbledon released its seeding lists. Out of 16 men, only Czechoslovakian Jan Kodeš was not an ATP member. The event got a bit of a reprieve when second seed Ilie Năstase also said he would play, apparently because the Romanian federation ordered him to do so. As David Gray wrote for the Guardian in a front-page story, it was shaping up to be an “Iron Curtain Wimbledon.”

Many women were sympathetic; a few were even prepared to join the ATP’s boycott. Billie Jean, though, was hunting bigger game. “We are in a great bargaining position,” she said, thinking about the appeal of Margaret Court, Chris Evert, Evonne Goolagong, and herself at a sold-out showpiece tournament bereft of its leading men.

Wimbledon planned to pay out the equivalent of $70,500 in prize money to the men and $50,500 to the women. By the standard of tennis distributions in 1973, the imbalance wasn’t egregious. But King targeted full equality, even when her fellow players thought it impossible.

“As for the girls wanting more money,” said tour regular Patti Hogan, “aside from the fact that it can’t be done, there’s no way we could justify this to the public.”

Others didn’t even care. Goolagong said, “I’d be happy to play at Wimbledon even if there was no money.” Evert, who had yet to adopt Billie Jean’s way of thinking, had similar priorities. “I’ve come over here to play tennis,” said the 18-year-old, “and that’s all I’m interested in.”

Once again, King was forced to play the long game. Without a united front that could take on Wimbledon organizers, she sought to create one. On June 20th, she held a meeting at London’s Gloucester Hotel for more than the 60 of her fellow players. By the end of the evening, she had convinced her peers that they needed a players’ union of their own. The Women’s Tennis Association was born. There would be no women’s boycott at the All-England Club, but the new organization would make its presence felt before the summer was through.

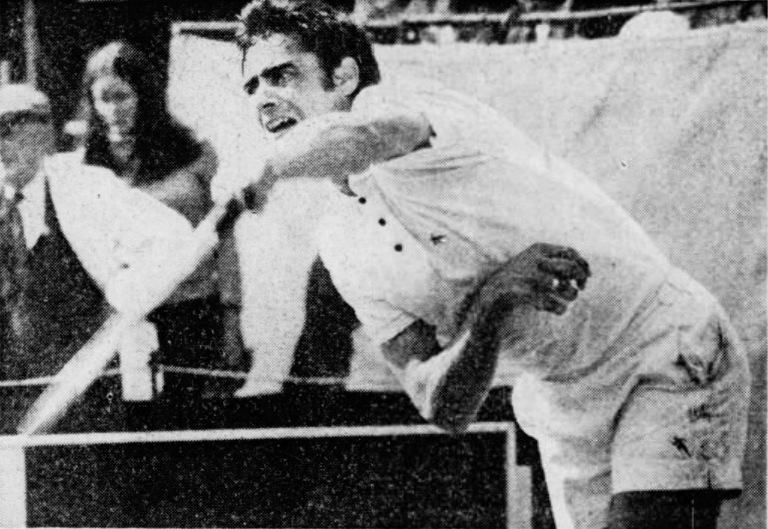

In the meantime, Niki Pilić flew home to Yugoslavia. He knew that the battle wasn’t really about him anymore. But this was still Wimbledon, where Pilić had reached the semi-final in 1967. If a compromise did emerge, he was ready to fly back at a moment’s notice.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: