The week before the French Open, the 1973 Davis Cup really got rolling. 16 European Zone nations and a passel of famous names squared off in head-to-head ties scattered from Cairo to Oslo.

Many stars made their first Cup appearances of the season when the ties opened on May 18th. Ilie Năstase won in straight sets as Romania took on Tom Okker and the Netherlands. Czechoslovakia’s Jan Kodeš made quick work of his Egyptian opponent, Ibrahim Mahmoud. Manuel Orantes of Spain turned in the best performance of the day in Båstad, Sweden, defeating 16-year-old Björn Borg with the loss of just four games.

There were surprises, too. Great Britain boasted two standouts from the World Championship Tennis circuit, Roger Taylor and Mark Cox. Yet on clay in Munich, they fell to a 0-2 deficit against West Germany. The British stars lost to Karl Meiler and Jürgen Fassbender, respectively.

The day’s heroics belonged to the overlooked Soviet player Teimuraz Kakulia, who outlasted his Hungarian foe, Balázs Taróczy, 1-6, 6-0, 6-8, 7-5, 7-5. Alex Metreveli made progress on the Soviet Union’s second victory, but Kakulia’s three-and-a-half-hour struggle had pushed it so late that his teammate wasn’t able to complete the second match until the next day.

At the start of the weekend, the tie between Yugoslavia and New Zealand seemed to be one of the least important of the lot. (Countries who didn’t belong to an existing geographical zone could choose which one to enter, which is why the Kiwis were competing in Europe.) Neither nation boasted any big-name stars, and whichever side advanced would almost certainly lose to Romania in the next round.

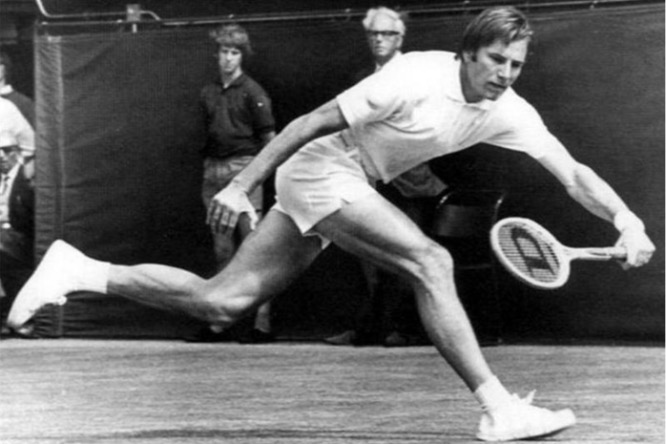

Of course, the two squads themselves didn’t see things that way. The Yugoslavians had looked forward to the return of 33-year-old left-hander Niki Pilić, a Croatian who ranked as his country’s best. Pilić had been a Cup stalwart from 1961 to 1967, helping his team to a zonal final in 1962 and quarter-finals in the three following years. But in 1968, Pilić had signed on with the WCT circuit. That made him a “contract professional,” ineligible for Davis Cup play.

Only in 1973 did that rule finally change. The Australians could once again use Rod Laver, and the Yugoslavians regained their own lefty star, Pilić. Or so they thought. The Yugoslavian captain was under the impression that Pilić had committed to play–or perhaps he simply assumed that every one of his country’s players was at his disposal. Niki would claim that he never made any promises. He entered the Alan King Classic in Las Vegas instead. He lost early and, in theory, could have made it to Zagreb in time for the tie. But he cabled team officials to confirm that he wouldn’t be there.

The hosts could have used him. On the 18th, Boro Jovanović lost a four-setter to Onny Parun. Željko Franulović, the last-minute Pilić replacement, pulled out a five-set victory over Brian Fairlie to even the tie. The Kiwis won the doubles in a rout, and Parun beat Franulović to clinch the victory.

The same day that the Yugoslavians lost the doubles rubber, the federation hit back at its wayward star, suspending him for his “refusal” to play the tie. It was a serious penalty: Without the blessing of his national association, Pilić wouldn’t be allowed to enter the French Open, Wimbledon, and many other prestigious events. His only recourse was to appeal to the International Lawn Tennis Federation, which he quickly did.

Ironically, Pilić, with his competing loyalties, was one of the few top men to enjoy several days of rest before play began at Roland Garros. He didn’t even know whether he would be allowed to enter, but at least he didn’t have to make a mad dash from Las Vegas or Båstad for his first-round match.

While Yugoslavia was out of the Davis Cup, l’affaire Pilić would cast a long shadow over tennis’s summer of 1973. For 70 years, young men had dreamed of one day playing Davis Cup for their countries. Now, as professionals, they would fight for the right not to.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: