By 1973, Stan Smith didn’t have much left to prove. He won the 1971 US Open, then took the Wimbledon crown in 1972. For five years running, he had been a key part of the USA’s champion Davis Cup team, staring down the hostile Romanians in Bucharest to cap his 1972 campaign.

But there was one thing Smith’s feats had in common: Rod Laver hadn’t been there. The Rocket skipped the 1971 US Open, and he was kept out of Wimbledon the following year when the Championships banned contract professionals. Contract pros were also excluded from Davis Cup, so the Australian team couldn’t use Laver, Ken Rosewall, John Newcombe, or Tony Roche–a foursome that would’ve made the Aussies overwhelming favorites under different rules.

In 1973, Smith himself was a 26-year-old contract pro, playing for the World Championship Tennis circuit alongside Rod. Davis Cup would finally be open to everyone, as well. Before the season began, Laver held a 5-2 advantage in the head-to-head, including wins in all three of their meetings at majors. Rocket padded his total with a victory in the Toronto semi-finals in February, then another for the Hilton Head title in March.

For more than a decade, Laver had been the man to beat. At age 34, he still was.

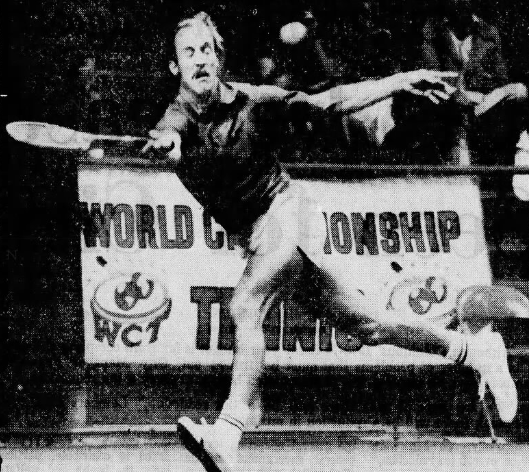

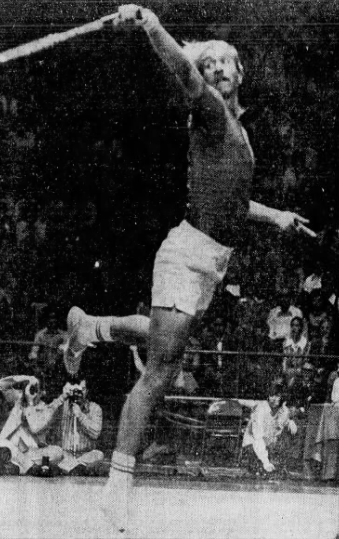

Both men played well to reach the Atlanta final. Each was pushed to three sets in the quarters but recovered for a dominant semi-final performance. Smith blasted past his frequent nemesis, Cliff Richey, 6-3, 6-2, and Laver, the event’s top seed, turned in one of his strongest showings of the year to shut down Cliff Drysdale, 6-2, 6-1.

The final promised to be a fitting conclusion to exciting week of tennis. The tournament announced a seven-day attendance of 47,524, a record for a WCT event. Among the crowd on Sunday was Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter and his wife. It was a far cry from the old days of barnstorming pros when Laver, Rosewall, and Richard González would stop in Atlanta for a night, lucky if they drew 3,000 fans.

Laver won many of his matches before the first ball was struck. “There’s always the danger of being psyched out by playing Rod,” said Smith after the match. “I mean you think the guy is so good and you don’t know what you have to do to beat him.”

On the other hand, Stan wasn’t the sort of player to be psyched out. Fellow players considered him confident to the point of arrogance. He also had a knack for ignoring anything that might get in his way, a particularly useful skill when he took on the eminently distracting Ilie Năstase for the 1972 Wimbledon and Davis Cup titles.

In the end, the mental game might have been beside the point. Standing six-feet, four-inches tall, Smith owned one of the biggest serves on the circuit. On this day, it was even deadlier than usual. He won 37 of 44 service points. Only once did Laver manage more than one return point in a game. The Rocket didn’t attack as much as usual behind his own serve, and Smith took the match, 6-3, 6-4.

The American was proud but realistic. Holding his $10,000 winner’s check, he said of his opponent, “He’s still the best.”

Rocket wasn’t one to argue. A little while later, he came back out on court with his old friend Roy Emerson and won the doubles.

* * *

This is the third installment in what I fear will be an ongoing series about 1973, perhaps the most consequential season in modern tennis history. Check back throughout the year for the latest news from, uh, fifty years ago.