Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. Hope I didn’t forget anybody…

* * *

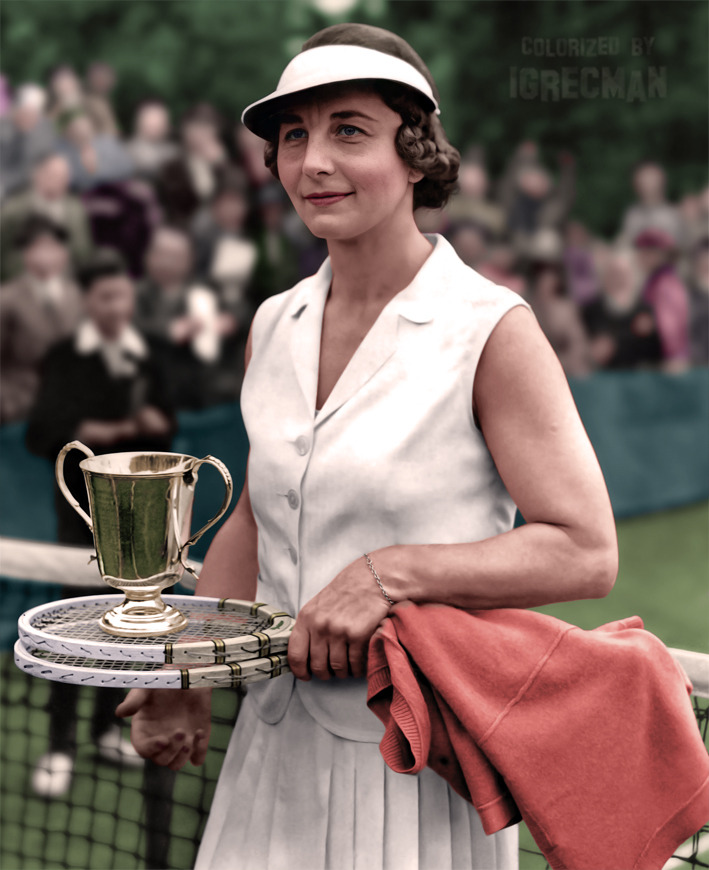

Helen Wills [USA]Born: 6 October 1905

Died: 1 January 1998

Career: 1920-38

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1927)

Major singles titles: 19

Total singles titles: 56

* * *

When Helen Wills lost the Match of the Century to Suzanne Lenglen in February 1926, she was not the best player in the world. Her supporters had clamored for a Wills-Lenglen showdown for years, back to 1924, when Helen traveled to Europe for Wimbledon and the Olympics. Lenglen pulled out of both events, leading some fans to believe that the French champion was afraid of her American challenger.

There was plenty for fear in Wills’s game. Even in 1924, when Helen was 18 years old, she probably hit harder than any other woman alive. While it’s possible that Molla Mallory had a stronger forehand, Wills wielded weapons on both wings. Helen finished runner-up in her first Wimbledon, to Kitty McKane, but she won the Olympic gold with ease. She dropped only sixteen games in four matches, including a routine defeat of Mallory.

When Lenglen and Wills finally met at Cannes, the veteran triumphed. Suzanne was steadier, and she was much the better mover. Helen’s edge in power, on its own, wasn’t enough. Years later, Lenglen said that no opponent could hurry her enough to miss into the net–“except Helen Wills a little.” The 6-3, 8-6 result revealed that Suzanne was the superior competitor, even as the gap between the two was shrinking.

Wills, for her part, was ready for another crack at the champion right away. “I am sorry Miss Lenglen has gone off to Italy,” she let slip to a reporter. “Don’t you feel she should have given me a return match here?”

The two women never played each other again. Wills withdrew from both Roland Garros and Wimbledon with appendicitis, and Lenglen turned professional later that year.

We’ll never know how the Frenchwoman would have handled the steadily improving Helen. Suzanne desperately wanted a chance to prove she remained the best, but Wills had no desire to turn pro, despite offers that reportedly reached $100,000–about $1.6 million in today’s dollars. The American amateur tennis authorities jealously guarded their turf; they weren’t about to sanction a match against a professional.

Wills had her weaknesses, some of which she never overcame. We’ll get to those in a minute. But there’s no doubt she became a better player than the version that lost to Lenglen. One of her practice partners said she was “50% better” in 1928 than she had been the year before.

Without Lenglen, the ever-stronger American had no competition. She won 16 of the 17 majors she entered between 1927 and the end of her career. She won 180 matches in a row in the first six years of that span, going much of the streak without dropping a set. She grabbed the number one ranking the moment Suzanne departed, and she never let go.

* * *

Superficially, the keys to the Wills game were her groundstrokes, particularly her forehand. Opponent weren’t accustomed to the pace, and few of them could keep up.

Anna Harper was the runner-up for the 1930 US national title, and she lost all five of her career meetings to her fellow Californian. “Those shots of hers, coming one after another after another without relief,” she said, “well, after a game or two when you found out how hard this was going to be, she either broke your confidence or she broke your arm.”

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

In 1927, the New Yorker described the Wills forehand as “plain ruination, so utterly drastic as to reduce her opponent’s assignment to the mere task of signalling hits and misses.”

Helen herself had no problem with pace. Like Lenglen, she preferred to practice with men. She prepared for her 1924 European trip by sparring with some of the best, including two-time national champion Bill Johnston. They peppered her with the hardest shots they could muster. She usually got them back, and she occasionally won practice sets, as well.

Only one woman in the 1920s could withstand the onslaught: Spanish star Lilí de Álvarez. Their 1927 Wimbledon final was a non-stop fireworks display. Bill Tilden thought he’d never seen women hit the ball so hard. Álvarez reached 4-all in the second set, when the contenders gutted out a 40-stroke rally. Both women doubled over, leaning on their rackets for support. Only Wills recovered. Álvarez didn’t win another point.

Most women never dreamed of making it to 4-all. Lenglen didn’t hit as hard, and she would sometimes toy with opponents to give the crowd a better show. Wills was all business. At the 1927 Wimbledon warm-up in Beckenham, she beat the South African Billie Tapscott in 18 minutes. She then disposed of Mallory in 23.

At a North American tournament the same year, she needed only 34 minutes to win the final against Helen Jacobs. It helped that she won the first 20 points in a row. I ran across one match report of a landslide that Wills polished off in 14 minutes.

John Tunis called Wills “a mechanical marvel reducing her adversaries to sawdust in as short a time as possible, asking no quarter and giving none.”

“To play Helen Wills,” wrote Jacobs, “was to play a machine.”

* * *

Jacobs knew that mechanics weren’t the whole story. In her chapter-length review of Wills’s career, she used the word “concentration” five times:

Helen Wills fought on the court much as Gene Tunney fought in the ring–with implacable concentration and undeniable skill, but without the color or imagination of a Dempsey or a Lenglen.

Her mantra on court was “every stroke, every stroke, every stroke.” After a bit of sociability early in her career, she rarely spoke to opponents. She smiled even less often.

“When she steps on a tennis court,” said her childhood coach William “Pop” Fuller, “all but the game ceases to exist.”

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

Ed Sullivan (yes, that Ed Sullivan) gave her a nickname in 1922: “Little Poker Face.”* It was later expanded to “Little Miss Poker Face.” She also gained another, less charitable moniker: “The Ice Queen.” Wills didn’t object. “I considered it a compliment because composure is the greatest asset you can have in sports,” she said in 1952. “If I hadn’t naturally possessed such intense concentration I would have tried to cultivate it.”

* The coinage is sometimes credited to Grantland Rice. I think Sullivan got there first. But Rice made all the same observations. 16-year-old Helen was “intensely serious, unemotional, stoical–not only for a girl of her age, but for a human being of any age.”

On the rare occasions that the forehand failed her, Wills’s concentration saw her through. In the 1930 Wightman Cup, she fell behind 5-0 to Phoebe Watson and came within two points of losing the set. She finally switched up her tactics, broke the Brit’s momentum, and won the match, 7-5, 6-1.

Many sportswriters pointed to the match as evidence that Helen was beatable. The players came to the opposite conclusion. No matter what you did, or how well you were playing, the Ice Queen had the answer.

* * *

Wills hadn’t always been so resilient. Her weakness, especially as a young player, was her movement. Danzig described the teenage Helen as a “statuesque, slow-moving base-liner.” He didn’t mean she looked like a statue–the point was that she moved like one.

It wasn’t usually a problem. Women’s tennis was almost entirely played from the baseline. Wills came forward twice in the 1924 Olympic final and was passed both times. Still, she won 6-2, 6-2.

One of the few women who could expose Helen’s subpar mobility was veteran doubles champion Elizabeth Ryan. Ryan’s game was built around chops–sliced balls that served as the perfect disguise for drop shots. In 1925, Wills arrived at the Forest Hills warmup in Seabright on an undefeated streak that stretched back more than a year. The 33-year-old Ryan took advantage of a soggy grass court and chopped her way to a 6-3, 6-3 upset.

In 1926, Helen came to Seabright on another winning streak, this one dating back to her loss to Lenglen in February. Ryan beat her again, this time allowing the national champion five games instead of six.

Little Miss Poker Face made some progress: Danzig called her a “pulsating antagonist of mobility” in 1927. But the real problem for Wills’s opponents was that she didn’t give them an opportunity to mix things up, whether that meant forcing Helen to cover the forecourt or attacking the net themselves.

Al Laney found Helen most interesting when she was not in top form. She could control a match despite barely moving from the middle of the baseline. “One often wondered why the silly girl did not make Miss Wills run,” he wrote, “until one realized that the silly girl had more than she could do merely knocking the ball down the center.”

* * *

One class of opponents could force her out of position and sometimes even defeat the queen: men.

This is the part of the Helen Wills story I find most compelling. It’s irrelevant to her status among the greats of women’s tennis. But a half-century before the Battle of the Sexes, Helen was practicing against men, playing exhibitions against them, and sometimes winning.

Lenglen had played practice matches with men in front of spectators as a teenager, but she increasingly shied away from the practice as she got older. She had an aura to protect. When a professional promoter suggested she play doubles on court with three men, she violently objected.

In the fall of 1926, Wills entered the men’s doubles tournament at her home club in Berkeley. She and Ward Dawson reached the final and served for the match before losing narrowly to Bud Chandler and Tom Stow.* The newspapers blamed the loss on Dawson.

* A future mentor and coach, respectively, of Don Budge.

One anonymous contemporary told Helen’s biographer, Larry Engelmann, that “the only men Helen Wills ever beat in a tennis match were real gentlemen.”

Phil Neer, an NCAA champion and frequent exhibition partner, insisted he played at full strength against Helen. Sometimes he won; often he lost.

The most tantalizing results are those from a pair of practice matches between Wills and Fritz Mercur in 1929. Mercur was good enough to have beaten Bill Tilden the year before. The first time they played, Helen won two sets. After word got around, they played again, and presumably the reputational stakes were a bit higher for Fritz this time. He took two sets from Wills. They played a third, in which Mercur wasn’t allowed to come to net. Helen won that one.

* * *

Wills was able to play those matches against men thanks to a no-nonsense attitude that couldn’t have differed more from Lenglen’s. She wasn’t worried about losing the public’s affection just because an exhibition match went sideways.

That isn’t to say Helen wasn’t famous. At first, she gained from Suzanne’s global reputation: Wills was the home-grown contender for the world crown, the Girl From the Golden West. Her simplicity and her shyness worked in her favor. Stories comparing the two wrote themselves: Lenglen was a leading member of the demi-monde; Helen was in bed every night by ten.

When Suzanne left the scene and Wills won at Wimbledon–and then again, and again–Helen was promoted even further. She became the American Girl.

The public marveled at her beauty. Female athletes were usually–at least in the conventional view–women who didn’t have what it took for other pursuits. The educated, classically beautiful Wills busted the stereotype. Her picture appeared in every newspaper, and sportswriters pointed out that she was even more striking in person. Her workaday tennis visor sparked a fashion trend. Artists from Alexander Calder to Diego Rivera found her an inspiration.

“All the males of America from six to sixty,” wrote one editorialist in 1927, “are a little in love with her.”

The American Girl was compelling enough that no one minded her ruthless domination of the game. After Ryan beat her in 1926, she dropped a decision to Mallory the following week. And that was it. She didn’t lose again for seven years.

* * *

Seven undefeated years. Even that doesn’t quite cover it. She lost a set in her opening match at the All-England Club in 1927. She didn’t lose another until the Wimbledon final in 1933.

Queen Helen took the “triple crown”–titles at the French, Wimbledon, and Forest Hills–in both 1928 and 1929. Had she been coaxed to play in Australia, she surely would’ve won there as well.

She had no rivals. There was only Helen Jacobs, the number two American. It was almost as good a story as Wills and Lenglen: The two women grew up on the same street and went to the same schools. But the results between Helen I and Helen II fell flat. When Wills–she became Mrs. Frederick Moody in 1929–won the 1932 Wimbledon title, 6-3, 6-1, she improved her career record against her townswoman to 9-0.

Only age and injury slowed her down. Dorothy Round gave Mrs. Moody her hardest fight in years at Wimbledon in 1933, successfully moving her around as women had so long tried and failed to do. Back in the States, she skipped the Wightman Cup with leg pain. She retired from the US national final with back troubles.

The 1933 Forest Hills title match was an enormous controversy at the time. You can still rile up your neighborhood tennis historian if you pick the wrong side. Wills Moody quit down 0-3 in the third set, showing no sign of physical illness. Did she do it just to deprive Jacobs of a proper victory? The Helens didn’t like each other, though the diplomatic Jacobs called it “incompatibility,” not a “feud.”

* I go into more detail in my Jacobs essay. It was a feud, at least in one direction.

Whatever was going through the Ice Queen’s head that day, her dominance of Helen II was over. Two astonishing winning streaks–180 matches, 45 at Forest Hills–were at an end.

* * *

Helen Wills Moody had always played down tennis’s role in her life. She skipped major events to attend classes, or just because she wearied of the travel. She would tell friends she went an entire winter without picking up a racket.

In reality, she maintained a rigorous practice schedule. She kept to a simple, steady diet. She didn’t go to parties until after she retired. She might not have smiled much, but she loved the game, and her position at the pinnacle of the sport was important to her.

She missed the entire 1934 season as she recovered from the injuries that compromised her play the previous year. In 1935, she went to England and lost in Beckenham to the British left-hander, Kay Stammers.

“She is not as great as she once was,” wrote the New York Times. “She is not as quick getting to the ball and shows signs of tiring more easily.”

Helen’s groundstrokes, however, remained fearsome. Her mind was as strong as ever. She held off a match point to defeat Jacobs in the Wimbledon final for her seventh singles title at the Championships.

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

Wills came back once more in 1938. (She divorced in 1937 and reverted to her maiden name.) The field finally believed she was beatable. Alice Marble even went so far as to say that the Ice Queen was no longer the best player in the world, though she didn’t specify who replaced her. Mary Hardwick and Hilde Sperling both scored upsets in the weeks before Wimbledon.

But once again, the American Girl proved equal to everything Wimbledon could throw at her. Sperling pushed her to 12-10, 6-4 in the semis, and she met Jacobs in the final. It was another hard-fought battle, but only for eight games. Jacobs hurt her ankle, and Wills ran out a 6-4, 6-0 victory.

She left the gallery at the All-England Club with a familiar impression: the eight-time champion holding the winner’s trophy. But for me, the emblematic image of Wills’s career came seven years earlier, in 1931. She coasted to her seventh and last US national title with a 34-minute defeat of British star Eileen Bennett Whittingstall. Helen won 6-4, 6-1.

Near the end of the match, a courtside spectator noticed two drops of sweat on her forehead. Little Miss Poker Face could’ve worked harder; occasionally she did. But on a day like that, against yet another inferior opponent–why bother?

* * *

Previous: No. 11, Monica Seles

Next: No. 9, Chris Evert

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: