I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. It’s like an advent calendar, only I keep the chocolate.

* * *

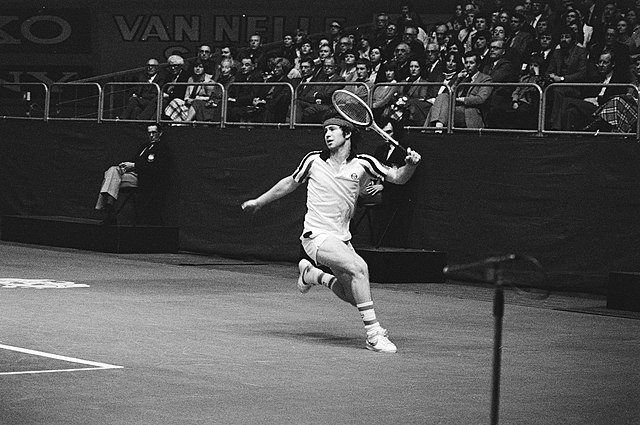

John McEnroe [USA]Born: 16 February 1959

Career: 1977-92

Plays: Left-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1980)

Peak Elo rating: 2,442 (1st place, 1985)

Major singles titles: 7

Total singles titles: 77

* * *

After the initial tennis boom of the 1970s subsided, Americans slid into the more sedate pastime of psychoanalyzing John McEnroe. Jimmy Connors and Ilie Năstase were easy enough to understand. To varying degrees, they were crude, showboating clowns with hair-trigger tempers.

McEnroe was something different.

The slim, pasty left-hander hardly looked like a world-class athlete, but he was undeniably gifted. He qualified and reached the semi-final at Wimbledon on his first try, in 1977. Just as quickly, he alienated stiff-upper-lip Brits along with tennis traditionalists worldwide. No mistake escaped his notice. He permitted himself no margin for error, and he treated others the same way. He never stopped to think before giving line judges–and chair umpires, and referees, and photographers, and reporters, and the occasional spectator–an often-profane piece of his mind.

London tabloids dubbed him “SuperBrat” and “McNasty.” The public leaned toward disapproval, but they didn’t dare look away.

Ion Țiriac, the coach and manager who handled Năstase, Guillermo Vilas, and Boris Becker, explained his appeal a decade later: “Half come to see him win. Half come to see him lose. Half come to see what happens.”

Everyone had a theory. McEnroe was spoiled. He was a typical New Yorker. He was standard-issue Irish. He didn’t care enough about tennis. He cared too much about winning. He got so bored that he manufactured controversy. He was the master gamesman. His outbursts were completely beyond his control.

Arthur Ashe knew the youngster as both opponent and Davis Cup captain. He took a stab at it: “He’s not that hard to understand. He’s just like any other twenty-three-year-old millionaire college dropout.”

Richard Evans took the opposite tack. Evans, a British journalist, ultimately wrote not one but two McEnroe biographies. The subtitle of the first, A Rage For Perfection, gives you an idea of how he assessed the champion in 1982. Eight years later, Evans came to this conclusion:

McEnroe is, above all, a complicated man–complicated to a degree far in excess of the public’s comprehension of just how complicated a human being can be.

Dear me. I’ll defer to Evans on that one.

Fortunately, McEnroe’s exploits between the white lines weren’t quite so inscrutable. He did things with a tennis racket that other men could barely imagine. His emotional instability was tied up with a belief–an expectation, even–that he could play perfect tennis. More than almost anyone before or since, he very nearly did.

* * *

It would be years before McEnroe could sustain a months-long stretch of perfection. But even in his teens, it was clear what he was capable of.

In 1978, while he lost early at Wimbledon, he reached the US Open semi-finals, where he lost to Connors. Then McEnroe went on a 38-3 tear, picking up titles in Hartford, San Francisco, Stockholm, and Wembley, then securing the Davis Cup final for the Americans.

The won-loss record made an impression, but what really woke up the tennis establishment was the way he played on his best days. The young man they called “Junior”–his father, also called John, frequently traveled with him–deferred to no one.

In Stockholm, McEnroe dealt Björn Borg his first-ever loss to a younger player. He barely broke a sweat. Borg lost 6-3, 6-4, and managed just seven points on McEnroe’s serve. The newcomer wielded an unreadable array of serves, acrobatic reach at the net, and tactical savvy beyond his years. When he wasn’t rushing the net, he neutralized Borg with easy “nothing” balls that negated the champion’s own ability to attack.

In the Davis Cup final, Junior conceded just ten games in six sets against Brits John Lloyd and Buster Mottram. “I have never played anybody, including Borg and Connors, who has been as tough and made me play so many shots,” said Lloyd. “No one has ever made me look like that much of an idiot.”

McEnroe thought he could’ve played better.

He finished the year ranked fourth on the ATP computer. Connors, whose lefty forehand erased some of the advantage of Junior’s slice serve, still had his number. Borg, no matter the result in Stockholm, held two of the four majors.

But the writing was on the wall. “Right now,” Ashe said after the Davis Cup final, “McEnroe is the best player in the world.”

* * *

A few months into the 1979 campaign, Borg was almost ready to concede as much. At the World Championship Tennis (WCT) finals in May, Junior beat Connors in straight sets, then upset Borg in four.

“I felt slow and always too late,” Borg said after the match. “When you play John you have to be absolutely on top of your game, or you lose immediately.”

Connors was no longer able to meet that standard. Jimbo won six of the first seven meetings between the two explosive Americans, but beginning with the 1979 WCT encounter, McEnroe won 19 of 27. Connors would always have it in him to deliver a memorable performance, as he did to take the 1982 Wimbledon title. But Mac was now the man.

At the US Open, Borg lost early, and McEnroe claimed his first major championship. He defeated Connors in the semis and Vitas Gerulaitis in the final, dropping only one set–to Năstase in the second round–the whole tournament.

It was his eighth tournament victory of the season, but his public image remained more bad-boy than champion. Gerulaitis summed up how the New York crowd viewed its two native sons: “Popularity-wise, I’m a notch above John, and John is a notch above Son of Sam.”

Had a couple of linesmen turned up dead, the authorities probably would have questioned McEnroe first.

Junior would take a major step toward salvaging his reputation with a heroic performance at Wimbledon the next year. At the site of his 1977 breakthrough, he met Connors again in the 1980 semi-finals. This time, the younger man won in four sets and advanced to a final-round meeting with Borg.

The result was one of the most captivating matches in tennis history. Junior was on his best behavior–he never did act out when he shared the court with the stoic Swede–but the contrast remained striking. The steady game of the champion and the electric shotmaking of the challenger had never been so evenly matched.

Borg had a chance to finish the job in the fourth set–seven match points, in fact. But it was not that the Swede failed at the critical moment, it was McEnroe who rose to the occasion. The American took the fourth set in a 34-point tiebreak so thrilling that dozens of fans back in Sweden died of heart failure.* Borg regrouped to win the match, 8-6 in the fifth, but if ever two men walked off Centre Court as co-champions, it was on that day.

* This feels like it must be apocryphal. I hope it’s apocryphal. But I tracked down a newspaper mention of the statistic as far back as 1982. So, um, be careful out there.

Johnny Mac’s home crowd still wasn’t quite persuaded to back the American. He heard his usual share of jeers as he turned the tables on Borg to win a five-set final at Flushing Meadow. He said, “I figure I’m about ten Wimbledon finals exactly like the last one away from getting those people on my side.”

* * *

McEnroe first claimed the number one ranking in March of 1980, four months before the Wimbledon final and more than a year after Ashe first proclaimed him the best in the world. He wouldn’t hold on: He’d swap places with Borg six times in a year and ultimately gain and lose the top spot on 14 separate occasions.

But in 1981, Junior left little doubt he was the king of men’s tennis. He beat Borg for both the Wimbledon and US Open titles. The 1980 Wimbledon final may have felt like a turning point, but I don’t think anyone walked away from that match believing it heralded the Swede’s almost immediate demise. In the event, McEnroe grabbed the reins, and Borg tumbled into a premature retirement.

Sports Illustrated offered a new reason for US fans to root against their champion: “McEnroe is getting so good he’s taking all the fun out of things.”

(J-Mac: “Fun? I enjoy the competition. But I was brought up to be very serious on the court, and I just can’t be what you call a crowd-pleaser.”)

Even more fun left the building in 1982, something of an off-year for the American. Ivan Lendl took Borg’s place as the top European, and he offered an even more dramatic contrast with McEnroe. His strokes were as robotic as Mac’s were natural, and he practiced more in a day than Junior did most weeks. The Czech beat McEnroe four times in four meetings, including a straight-set US Open semi-final.

Yet John, once again, proved himself capable of perfection. He won his last 24 matches of the season, running off four titles and finishing a perfect eight-for-eight Davis Cup singles campaign. Back in July, he had outlasted Mats Wilander in a record-setting six-hour duel just to reach the Davis Cup semis.

If there was anything that would earn McEnroe the adulation of fickle tennis fans, it was his undisguised passion for team play. One friend called him the best team player never to pursue a team sport. He was always available for Davis Cup, and with rare exceptions, he seemed to play even better with USA on his shirt.

Even apart from international competition, Junior was one hell of a teammate. Peter Fleming often said that the best doubles team of his era was “McEnroe and anyone.” Fleming, standing six-feet, five-inches with a serve to match, was being modest. The best team was McEnroe and Fleming. The pair won seven majors together along with dozens more titles between 1978 and 1986.

Much of the time, a doubles match for McEnroe was a lark, an ideal substitute for a boring practice session. But what fans rarely saw–and journalists even more rarely publicized–was that Mac was most dangerous on the doubles court after he had lost in singles. Unlike many of his peers and most of the superstars who followed him, he didn’t default to get an early start on the next event. He got serious.

McEnroe detractors lumped him in with everything they disliked about the modern game–money-grubbing primadonnas, you know the story. But while the volatile lefty could be a “maniac”–his word!–he didn’t share the other flaws. At Basel in 1978, he lost a tiring singles final to Vilas, injuring his elbow in the process. He took two aspirin, laid down for 20 minutes, and came back out to win the doubles title.

“The kid would have made a helluva player on the old pro tour,” said Jack Kramer, who generally reserved his praise for men no younger than Don Budge. “He’s got pride, he’s consistent, he plays hurt and he dislikes losing in front of anybody. I tell you what he is: The kid’s a throwback.”

* * *

In 1983, McEnroe pulled ahead of Lendl. In 1984, he gained the upper hand on everybody.

Junior delivered his most convincing defeat of Lendl to date in the 1983 Wimbledon semi-finals, then waltzed through the final against 91st-ranked Chris Lewis. In three sets, he lost only nine points on serve.

He went through the usual dramatics in the early rounds, throwing a racket, insulting an umpire, and prompting many of his fellow players to call for stricter enforcement against the champion. But no one could deny the quality of his play. Sports Illustrated put him on the cover–tagline, “Never Better”–and proposed that the only way Wimbledon could keep things interesting would be to create a new unisex bracket so that McEnroe could face the equally imperious women’s champ, Martina Navratilova.

In 1984, the entire tour was Chris Lewis. McEnroe posted one of the greatest seasons of all time. He went 82-3, winning Wimbledon, the US Open, and twelve more titles besides. At the All-England Club, he polished off Connors, 6-1, 6-1, 6-2. He committed only two unforced errors.

Two.

As staggering as the 82-3 mark sounds, even that doesn’t quite capture the duration of his peak form. First off, one of the three losses was a five-setter in the Roland Garros final. Any other season, and that would’ve counted as a shocking triumph for the fast-court specialist, even if the circumstances–he let the match slip away after he took the first two sets and picked a fight with a cameraman–hardly covered McEnroe in glory.

Second, he recovered from a painful finale to sustain his streak into 1985. For such a historic campaign, 1984 ended with a thud. McEnroe was kept out of the Wembley indoor event in November because he had drawn too many fines for bad behavior. (Ya think anybody would’ve beaten him there?) Then he took part in America’s embarrassing defeat to Sweden in the Davis Cup final. If Junior was typically a great man to have on the squad, he was hobbled in Gothenberg by the worst teammate of all: Connors. Neither man would’ve chosen the indoor clay surface of the tie. Jimbo lost badly, then McEnroe dropped the second rubber to Henrik Sundström–his third loss of the year. Mac and Fleming lost the doubles to Stefan Edberg and Anders Järryd to hand the Cup to the hosts.

No matter. McEnroe returned to action less than a month later, beating Järryd, Wilander, and Lendl for the Masters title. He won 22 in a row to start the season, good for a 15-month record of 104-3.

After defeating Connors in Chicago for his fifth title of 1985, McEnroe’s Elo rating–per my retrospective calculations–reached 2,442. That’s the third-highest mark of any Open era man, trailing only the very best form of Borg and Novak Djokovic.

Vic Braden analyzed John’s strokes and concluded, “[B]iomechanically he’s so perfect it looks like magic.”

McEnroe said in 1984, “I still think I can play better.”

* * *

Borg retired at the age of 26. McEnroe didn’t understand it at the time. Deprived of his greatest rival, he never quite forgave him for it.

But at the same age, similar pressures–family, celebrity, at least a touch of burnout–struck down the American. The 1984 US Open title would prove to be his last major championship. In 1985, he fell in the quarters at Wimbledon, then lost the Flushing final in straights to Lendl. He couldn’t derive the usual enjoyment from Davis Cup, since he wouldn’t sign a code of conduct that sponsors forced on the squad after the shambolic performance in Gothenburg.

At the Australian Open, McEnroe spent more energy arguing than attacking the net, and after a quarter-final loss to Slobodan Živojinović, his accumulated offenses triggered a 21-day suspension. The absence turned into seven months, as he stayed home with his bride-to-be, actress Tatum O’Neal, and the couple’s young son. He took another extended break after the 1987 US Open.

With seven majors and 170 weeks at number one, Junior had little to prove. Instead, he sought a healthier relationship with the game. “I don’t want to be like I used to be any more,” he told Richard Evans. “I have to learn to enjoy myself more and if that means I cannot be number one again, I am just going to have to accept that.”

Those of us who remember watching McEnroe in his final years can attest to fact that he never quite accepted it. But he did live with it. On any given day, he could summon the wizardry that conquered Borg, Connors, and the rest. A series of battles with Boris Becker were particularly memorable, even if they usually resulted in a victory for the German.

As it turned out, McEnroe the maniac couldn’t be separated from McEnroe the genius. Some players find they can’t sustain the demands of practice and preparation needed to stay at the top. Johnny Mac never bothered with that, so the fervor of an all-time great was channeled into mental and emotional turmoil.

Tennis fans still get glimpses of that intensity. McEnroe is ever-present, as a commentator, an exhibition star, a still-valuable brand endorser. He has given more thought to his psychological makeup than anyone else has, and he rarely gives a boring interview. As a result, we get a steady stream of documentaries and profiles of the former champ that, oddly enough, tend to focus on his failings.

There were plenty of those, to be sure. But it’s impossible to watch an early-1980s McEnroe match without recognizing that he was one of the most talented men ever to play the game. You can’t look at his career record and deny that he achieved as much as all but a handful of players in the game’s history. It’s illogical to cancel out the positives just because it was so easy to imagine him winning even more.

In 2002, McEnroe brought up an old saw: “As they say in sports, the older you get, the better you used to be.” It’s true of Borg, and Connors has done even better–the older he’s gotten, the nicer he used to be. Johnny Mac breaks the mold in the other direction, making sure every new generation of fans learns what was wrong with him.

Ease up, John. You cannot be serious.