I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. It’s like an advent calendar, only I keep the chocolate.

* * *

Ken Rosewall [AUS]Born: 2 November 1934

Career: 1950-80

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1961)

Major singles titles: 8 (15 pro majors)

Total singles titles: 147

* * *

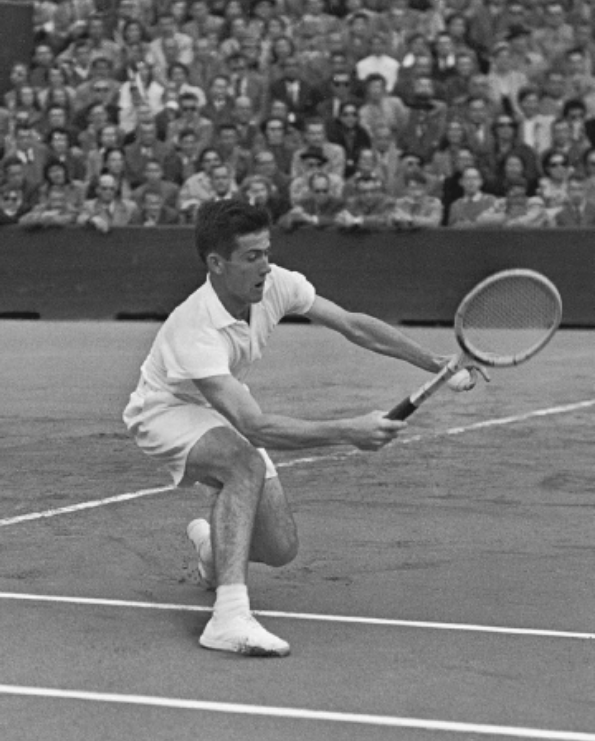

Ken Rosewall was always defined by his backhand. For much of his career, you’d hear experts proclaim it was the best shot off that wing since Don Budge. By the 1970s, fans started to whisper the unthinkable–maybe Rosewall’s was even better.

Not all backhands serve the same purpose. Rosewall, a 142-pounder standing a mere five-feet, seven-inches tall, lacked the physical tools to deliver the sledgehammer that came naturally to Budge. The Aussie’s famous one-hander wasn’t a notably heavy ball; he even struck it with a bit of underspin.

No, Rosewall’s backhand wouldn’t knock you down. Despite spending three decades holding his own against heavyweights like Lew Hoad, Richard González, and John Newcombe, he didn’t have a single offensive weapon that could compare with the body blows those men took for granted. His serve was a merely functional delivery, and his forehand paled next to those of his hard-hitting peers. If he was beating you–and he probably was–the backhand was the obvious explanation.

Rod Laver knew his game as well as anyone. The two undersized Australians faced off at least 164 times. “His backhand was readable,” Laver wrote, “but it was always so deep and accurate that unless you got to it and returned it solidly you were in trouble.” Fred Stolle, for his part, didn’t point to any particular weapon. He considered Rosewall’s strongest weapon to be his focus. “The pressure was on you every second,” Stolle said, “because you knew that when you hit a bad shot he would make you pay without fail.”

The more you hear what rivals said about the Rosewall game, the less the backhand–uncannily precise as it was–seems like the determining factor in his greatness. González thought that Ken’s forehand, taken on the rise, was similarly effective. Stolle said he would trade any one of his shots for the Rosewall forehand.

Rosewall’s serve was his apparent weakness. But like his backhand, it was unerringly accurate. During one critical match in 1971, he earned a few cheap points when his serves took bad bounces off a small patch of uneven court surface. He insisted he wasn’t aiming for it–after all, the target was barely the size of a salad plate. Friends and journalists were still skeptical. The important thing isn’t whether he was or wasn’t picking up those freebies on purpose, it’s that his rivals believed that he could.

Once he put the serve exactly where he wanted it, Rosewall’s game was defined by his feet. He seemed to play every rally as if it were a match point, and his impeccable footwork put him in position for every shot–backhand, forehand, volley, or smash. For René Lacoste in 1968, that was enough to make him the greatest of all time, “a complete athlete who combines intelligence with dexterity.”

Antagonists couldn’t believe that the pint-sized Australian could keep up the pressure for five sets. Yet he sustained his level for 25 years.

* * *

Rosewall emerged on the Sydney tennis scene as a pre-teen, already playing largely the same game he’d employ for decades. It won him matches when he was still in grammar school–a good thing, since it didn’t give anyone a chance to doubt whether the runty counterpuncher had what it took to become a champion.

He and Hoad were both born in November 1934. They became known as the “Tennis Twins” when they joined forces to lead the Australian Davis Cup squad and take on the world at the majors. But first, Lew had to pull even with his sporting sibling. The first several times they met as juniors, Rosewall beat him 6-0, including an exhibition match in front of the visiting American Jack Kramer. Even then, Kramer marveled at the intensity the youngsters mustered for a match with nothing on the line but pride.

By the time Ken came to the attention of Davis Cup captain Harry Hopman, Kramer’s “Big Game” revolution was underway. Frank Sedgman was playing first-strike tennis and inspiring the next generation of Aussies to do the same. Hoad–and Ashley Cooper, and Mal Anderson, and Neale Fraser, and Roy Emerson, and Laver–would follow suit. Rosewall was a rare exception in an increasingly serve-and-volley-dominated game.

Fortunately, Hopman was a talent scout and disciplinarian more than a tactician. He wanted hard workers with a burning desire to win. He didn’t care whether they played the way Kramer did. Hopman dubbed the young man “Muscles.” It was a joke: Rosewall didn’t have any.

The slender teenager made up for his size with textbook-perfect strokes. His father, Robert, earned extra money by renting out three clay courts behind the family grocery. He began teaching Ken to play at age three, patiently practicing one stroke at a time. Like the coaches of Margaret Court and Maureen Connolly, he made a right-handed tennis player out of a natural left-hander. The decision put a low ceiling on the Rosewall serve, but it made possible the famous backhand.

By the time Hopman got ahold of Ken, the flawless baseline game was in place. At one point, Robert took his son to a professional coach to fill in the gaps of his own teaching. The coach demurred–there was nothing he could add to what the boy already knew.

* * *

It is difficult to grasp the entirety of Rosewall’s accomplishments because the list is so long and varied. Roughly speaking, we can divide his career into three parts: amateur (1950-56), professional (1957-67), and the Open era (1968-80).

He made his first trip abroad in 1952, as a 17-year-old. From 1953 to 1956, he contended for major titles–winning four and reaching another four finals–and led the Australian Davis Cup side to three championships.

Ken’s early training on clay courts paid off. In 1953, he was the first Australian champion at Roland Garros since Jack Crawford two decades earlier. He had a heartbreaking near-miss at Wimbledon to Jaroslav Drobný in 1954, then came up short at the Championships again in 1956. That year belonged to Hoad. The larger of the tennis twins finally gained control of his overpowering game, and he won the first three majors of the season.

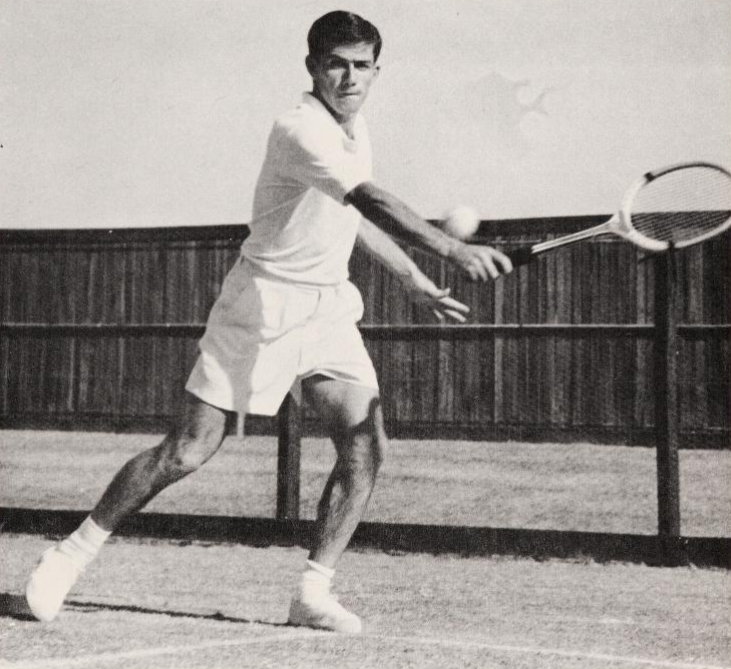

Rosewall’s feet were almost always in the right place. (With Hoad, at Wimbledon in 1954.)

Hoad came within one match of the Grand Slam. His opponent for the Forest Hills title was Rosewall. Hoad won the first set and took a 2-0 lead in the second. From there, it was all Muscles. The challenger bounced back to win six straight games. Bill Talbert, the US Davis Cup captain, hailed Ken’s “needle-threading accuracy and remarkable court acumen,” describing him as “the master—a crafty tailor sewing a garment of defeat for his victim.”

Indeed, another of Ken’s nicknames in those days was the “Little Master.”

Even before the higher standards of the professional game forced Rosewall to eke every last bit of potential out of his serve, onlookers were often surprised just how effective his delivery was. Talbert noted after the 1955 Davis Cup Challenge Round that Muscles “served brilliantly”–giving Vic Seixas nothing to attack in the first rubber. In the final set of the 1956 Forest Hills final against Hoad, Rosewall surrendered only three service points.

According to Dinny Pails, the 1947 Australian champion who would later face Rosewall as a pro, “He doesn’t win matches with his serve, but he doesn’t lose any, either.” Not overwhelming praise, but for a man with deadly aim from the backcourt, it was enough.

* * *

The second phase of the Little Master’s career was an eleven-year run in the professional game. Rosewall signed with Kramer at the end of 1956. Two weeks after he made it official, he faced Richard González for the first time, taking him to five sets in Melbourne.

Ken’s career from 1957 to 1967 were dominated by his rivalries with González and Rod Laver. For the first few years that Muscles played for money, Gorgo was the only man who could consistently beat him. Laver took over that role in 1964, but only after losing 38 of 51 meetings with his countryman in 1963.

Keep in mind, Rocket Rod was four years younger. By the time the two men began their professional duels, Rosewall was 28, with more than a decade of competitive tennis in his legs.

It’s also important to remember that conditions on the pro circuit were tilted in favor of big servers like Gorgo, Laver, and well, just about every professional except Ken. Most matches in North America were played on fast canvas courts, indoors. Tournaments in Europe were often held in the amateur offseason, indoors on equally speedy wood.

When the professionals gathered on clay, the Little Master was particularly tough to beat. The French Pro–one of the unofficial majors of the pay-for-play circuit–was held at Roland Garros until 1962. That edition marked Rosewall’s third straight title at the event, his fourth overall. Remarkably, he’d go on to win another four straight championships despite the venue shifting to indoor wood courts at Stade Pierre de Coubertin.

Our records of this era are incomplete, especially apart from the major rivalries. But it’s clear that Rosewall held sway over everyone not named Laver or González. (And we shouldn’t take that caveat too far. He beat Gorgo 87 times, Rocket 75.) No one else managed a winning record against Ken in this eleven-year span. Against the rest of the pack–predominantly skilled, veteran operators who merited a spot in the world’s top ten at some point in their careers–Rosewall played another 700 matches. He won more than three-quarters of them.

As he dismantled one serve-and-volleyer after another, Ken picked up yet another nickname. He was the “Doomsday Stroking Machine.”

* * *

The final phase of Rosewall’s career began when the amateur era ended.

Anyone who doubted that the professional game had monopolized the world’s best players was quickly set straight. At the first Open tournament in April 1968, at Bournemouth, Muscles beat Laver for the title. A month later, the same two men played for the first Open major title. The result was the same. Fifteen years after his first triumph at Roland Garros, Rosewall added his second.

Other than the majors and a few other mixed events, Ken’s competition didn’t change much that first year. He was part of George MacCall’s National Tennis League (NTL), where he faced the likes of Laver, González, and Emerson, week in, week out. Laver won five of their seven meetings, but he was the only man on the circuit with a clear edge over the Little Master. One journalist ranked 34-year-old Rosewall as the year-end number two. Another placed him third, behind Arthur Ashe. The one time Rosewall and Ashe faced off, at the Pacific Southwest in September, the Australian lost just five games.

In 1969, Rosewall reached another French final. But like the rest of the field, he sat back and watched as Laver won the Grand Slam. No one would have been surprised if Rosewall had gracefully faded away.

Instead, Muscles played better than ever. He had always regretted his near-misses at Wimbledon. Contractual issues kept him out of the 1970 Australian and French Opens, so the Championships were his first major of the season. Fourteen years after his last appearance in the final, he defeated Tony Roche in the quarters and British hope Roger Taylor in the semis.

John Newcombe, a big-serving Aussie ten years Rosewall’s junior, waited in the final. Newk was yet another big server looking to hit through the veteran, and like González, he had the raw power to do it. Muscles was the sentimental favorite, but when he fell behind, 1-3, 0-30 in the fourth set, it seemed to be over. Somehow, Ken saved the game with four straight points. He ran the streak to 12, and won 20 of 23 points to take the fourth set. Alas, Newk was too strong in the fifth, and Rosewall went home with his third Wimbledon runner-up trophy.

The veteran got his revenge at Forest Hills. In the quarter-finals he knocked out the promising young American Stan Smith. Walter Bingham wrote for Sports Illustrated that Smith “looked like a dinosaur trying to stalk a mongoose.” Rosewall drew Newk again in the semi-finals. This time, no heroics were needed. Muscles committed only seven errors in three sets. World Tennis wrote, “There were moments when one felt one had never seen anyone, anywhere, play better.”

Rosewall sealed the US Open title by beating Roche in a four-set final. He lost only two sets the whole way, prompting Bingham to quip that Muscles was playing twice as well as he did to win the title in 1956, when he lost four. The Doomsday Machine didn’t need to do anything special, as he explained to a reporter afterwards. “I played my regular game,” Ken said. “I hit a few serves and a few volleys.” Wealth and fame had not made the man any more voluble.

* * *

At age 36, Rosewall was, in the eyes of many pundits, the top player in the world. (Bud Collins ranked him behind Newcombe; my Elo ratings place him behind Laver.)

In 1971, he added another major title by defeating Ashe for his first Australian title of the Open era. He fell to Newk again at Wimbledon but redeemed himself at the World Championship Tennis (WCT) finals in November. The tournament was essentially the year-end championship for the top pros, and Rosewall knocked out Newk, Tom Okker, and Laver for the crown. A month after that, he defended his Australian title for his eighth career major title.

Despite all the slam finals, the signature match of the Little Master’s late career took place at an upstart event, in Dallas. The WCT shifted its schedule between 1971 and 1972, so Rosewall’s 1971 championship was only good for six months. The 1972 WCT finals came up in May. The cast of characters was nearly the same. The title match, once again, would be contested between Rosewall and Laver.

Steve Flink has called it one of the three greatest matches of the Open era, right up there with the Borg-McEnroe Wimbledon final of 1980 and the Federer-Nadal meeting at Wimbledon in 2008. It was no secret at the time: 21.7 million viewers tuned in for live coverage on NBC, the largest television audience for a tennis match to that point, and still the second largest behind the 1973 Battle of the Sexes. The winner received $50,000 (about $350,000 in today’s dollars) and a Lincoln Continental.

Laver was the pre-match favorite, having won their three meetings on the WCT circuit that year. But, he later wrote, “when your opponent is Ken Rosewall, all bets are off.”

The favorite took the first set, 6-4, but Muscles bounced back with another of his irresistible streaks to win the second, 6-0.* Rosewall took the third, then Laver forced a decider with a fourth-set tiebreak.

* “Getting beaten to love simply never happened to Rocket Laver,” Rod later wrote. Indeed, it was only the third bagel he suffered in the Open era, a span of over 450 matches. Rosewall also dealt him the first of the three, at Bournemouth in 1968.

The 37-year-old and his 33-year-old challenger were both on their last legs as the match entered its fourth hour. The 7,800-strong crowd cheered every rally. Rosewall took an early break lead; Laver fought back. Muscles reached match point at 6-5; Rodney saved it with an ace. Another breaker would determine the 1972 WCT champion.

Laver edged ahead, reaching 5-4 on his own serve. For what must have felt like the millionth time, the game’s greatest counterpuncher reversed the usual tennis logic. Sports Illustrated wrote, “Rosewall called up all his strength to jump on both of Laver’s first serves so fast the Rocket must have felt he was in a boomerang gallery.” Laver couldn’t manage the same on Ken’s final serve, and the match–“a blood-curdling, nerve-racking epic”–went to Muscles.

* * *

In 1974, Rosewall still believed he could win Wimbledon. “It takes luck and stamina,” he told Bud Collins. “But yes, I always think one year I’ll be champion. I believe in miracles.”

He had missed two chances. In 1972, WCT players were banned from competing. In 1973, 81 members of the newly-formed Association of Tennis Players (ATP) boycotted the event. It’s most common to speculate that Newcombe–winner in 1970 and 1971–would’ve picked up another title or two, or that 1972 champion Stan Smith could have defended his crown. But you have to believe Rosewall would’ve been in the mix.

As if to drive home the point, the Little Master returned in 1974 with a defeat of Newk in the quarters and Smith in the semis. But for the fourth time, 20 years after the loss to Jaroslav Drobný, Rosewall fell short in the final. This time Ken’s conqueror was 21-year-old Jimmy Connors, another all-court player with a backhand in the same league as Rosewall’s.

Ken repeated his feat at the US Open, knocking out Newcombe one more time. And again, he ran into Connors, who allowed him just two games in three soul-destroying sets. Couldn’t Jimbo have taken it easy on the old man? The brash new champion managed to to defend his ruthlessness with an uncharacteristically respectful response. “I’ve seen people pity Ken Rosewall and then see him win 6-3 in the fifth,” said Connors.

Muscles hung on in the top ten until 1976, 24 years after his first appearance on that list. He continued to enter tour events until 1980. At age 45, he won his first-round match at all three tournaments he played.

The feet slowed down, but Ken’s backhand never did. In their book The Golden Era, Laver and Larry Writer tell a story from Rosewall’s 1978 Australian Open match against Sherwood Stewart:

[T]hey engaged in a cross-court backhand duel, each backhand faster and lower than the last till the ball was barely clearing the net. Then without warning, Ken changed tack and drove down the line, leaving Sherwood, who was expecting another cross-court backhand, in a tangled mess on the court, laughing his head off. He cried out to Ken, “I’ve seen it but I don’t believe it! How much do you charge for lessons?”

Only then, with Muscles in semi-retirement, was the pressure finally off. Opponents could laugh at Rosewall’s exploits. But they had waited a long time to relax. Newcombe, for one, spent most of his career frustrated by the Doomsday Stroking Machine. When he lost to Ken at the 1974 US Open, it was the second consecutive major where first- or second-seeded Newk crashed out to the sharp-shooting 39-year-old.

He could only gripe to a reporter: “I wish he’d get old.”