I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. Beware of GOATs.

* * *

Richard González [USA]Born: 9 May 1928

Died: 3 July 1995

Career: 1947-74

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1948)

Major singles titles: 2 (12 pro majors)

Total singles titles: 111

* * *

One 1959 Sports Illustrated article managed, within the space of a few hundred words, to compare the professional tennis tour to no fewer than three other sports. The format was like heavyweight boxing. The standard of play was equal to a demand that golfers finish below par. And pro champion Richard “Pancho” González was the tennis equivalent of a wrestling “heavy”–the villain. He was the big guy, the dark-skinned one, the hard-hitter with a disposition that the word “surly” didn’t quite cover.

Myron McNamara, in charge of publicity for the pro tour that season, said, “Ponch acts like he thinks he’s defending the world’s heavyweight championship instead of the world’s tennis championship.”

You don’t have dig very deep into the González biography to understand why. After winning the US Championships as an amateur in 1948 and 1949, he turned pro at age 21. In a one-on-one series with reigning champion Jack Kramer, he lost 22 of the first 26 matches. The full tour went to Big Jake, 94 to 29.

Kramer later wrote that his opponent “got better as the tour proceeded, and by the end he was a much tougher competitor, and possibly even the second-best player in the world.” But a second-place ranking meant there was no place for him on the following year’s tour. Pro tennis really did work something like prizefighting. If a challenger couldn’t take down the champion, he might as well stay home.

After losing to Kramer, González accepted his fate. He bought the pro shop at his childhood courts in Los Angeles. He played occasional tournaments, but he mostly watched as other men–Frank Sedgman, Pancho Segura–took on Jake for the big money.

So when he landed a place on the tour in 1954, González acted like he was fighting for the world’s heavyweight championship because, well, that’s exactly what he was doing.

González was armed with effortless power and a competitive zeal that even he couldn’t quite understand. But that doesn’t mean it was easy to stay on top. When Lew Hoad turned pro in 1957, Kramer groomed the Australian specifically to topple the champion. González had to rebuild his backhand to stay ahead of the challenger. Jack March, the organizer of the professional tournament in Cleveland, changed the rules altogether. He limited players to one serve and switched to ping-pong scoring in an attempt to spice things up and level the field. A few years later, Kramer tried a “three-bounce” variation that forbade either player from coming to the net until three balls had been played from the baseline.

Even though González wasn’t the sole target of the rule changes, he spent nearly a decade with a bullseye painted on his back. It didn’t matter. One serve, two serves; one bounce, three bounces; tours, round robins, knock-out tournaments; against Sedgman, Hoad, Ken Rosewall, Tony Trabert, even Rod Laver–the tall Californian was equal to anything pro tennis could throw at him.

Kramer was there for the duration, first as the champion, then as a promoter. The men were business partners, antagonists, sometimes even friends. “No two people without a marriage license should ever get along so miserably,” wrote one columnist. However complicated their relationship, though, game recognized game.

“At 5-all in the fifth,” Kramer wrote, “there is no man in the history of tennis that I would bet on against him.”

* * *

Kramer rarely called his rival and star attraction “Pancho.” He opted for another, more personalized nickname, “Gorgo.”

After González’s surprise victory at Forest Hills in 1948, his motivation sagged. His results went in the same direction. He lost to Herbie Flam at Palm Springs in his first event of 1949. At River Oaks in Texas, he lost in the quarters to Sam Match. At the Southern California Championships, Ted Schroeder blew him off the court, 6-1, 6-0, 6-2.

There were so many holes in his game that people started to call him the “cheese champion.” Frank Parker ran with the joke and dubbed him “Gorgonzales”–after Gorgonzola cheese. That being a mouthful, it became “Gorgo.” González could be touchy about slights, perceived and otherwise, but this one didn’t bother him.

“Pancho,” however, did. At least sometimes. “Pancho” is traditionally a diminutive of “Francisco”–that’s how Francisco Segura became the “Little Pancho” to González’s big one. In 1940s California, however, it was also a blanket term for Mexican-Americans, maybe because Pancho Villa was the Mexican that white people knew best. “Pancho” was rarely uttered as an intentional racial slur. But the unthinking nickname was one of many small reminders that–in the eyes of the speaker, anyway–Mexican-Americans didn’t quite belong.

In 1957, González told a reporter he didn’t mind the name. (His family, did, though. Once when a friend came calling, his mother said, “I have no child named Pancho.”) Maybe he was feeling generous that day, or he became more sensitive later on. Born Ricardo Alonso, he anglicized his given name to Richard. He sometimes went by Dick. Friends called him Gorgo. Like all Gonzálezes, he was sometimes Gonzo. You can’t say the man didn’t give you options.

There’s the last name, too. Gorgo was known for most of his career as “Pancho Gonzales”–ending with an “s.” As Kramer understood it, his wife discovered that “González” was the spelling associated with upper-class Spaniards, and she encouraged him to change it. An alternate version is that his father, Manuel, after walking 900 miles from Chihuahua to settle in the United States, changed his name from González to Gonzales to make it easier for northerners to spell.

Schroeder once said, “He was a very prideful man, not proud, prideful. When you understood that, you understood him.” The words have shifted in meaning over the years, but I think Schroed meant that his friend was (extremely) self-assured, but not arrogant. González never forgot his treatment as a second-class citizen in his early life. Those memories and his undeniable, first-class athletic gifts could come together in an explosive mix.

I can understand if you prefer to call the man “Pancho Gonzales.” It was effectively his stage name for more than two decades. But I’m not going to do that. We can’t undo the insults, but we can at least try to spell his name right.

* * *

I try to steer clear of descriptions of the great players that focus on natural gifts. Thinking in those terms tends to obscure the immense amount of hard work required to convert raw talent to world-class tennis skill. In Gorgo’s case, though, there’s no getting around it.

González never had a coach. His mother gave him a cheap racket, hoping it would distract him from more dangerous pastimes. He learned to play on the neighborhood courts at Exposition Park. A friend named Chuck Pate gave him a few tips when he was doing something wrong, but that’s as far as it went.

“Even as a kid,” Pate said, “he had a bigger serve than the other kids. It just grew up with him.”

By the time he reached his full height of six-foot-three, he had a bigger serve than the other adults, too.

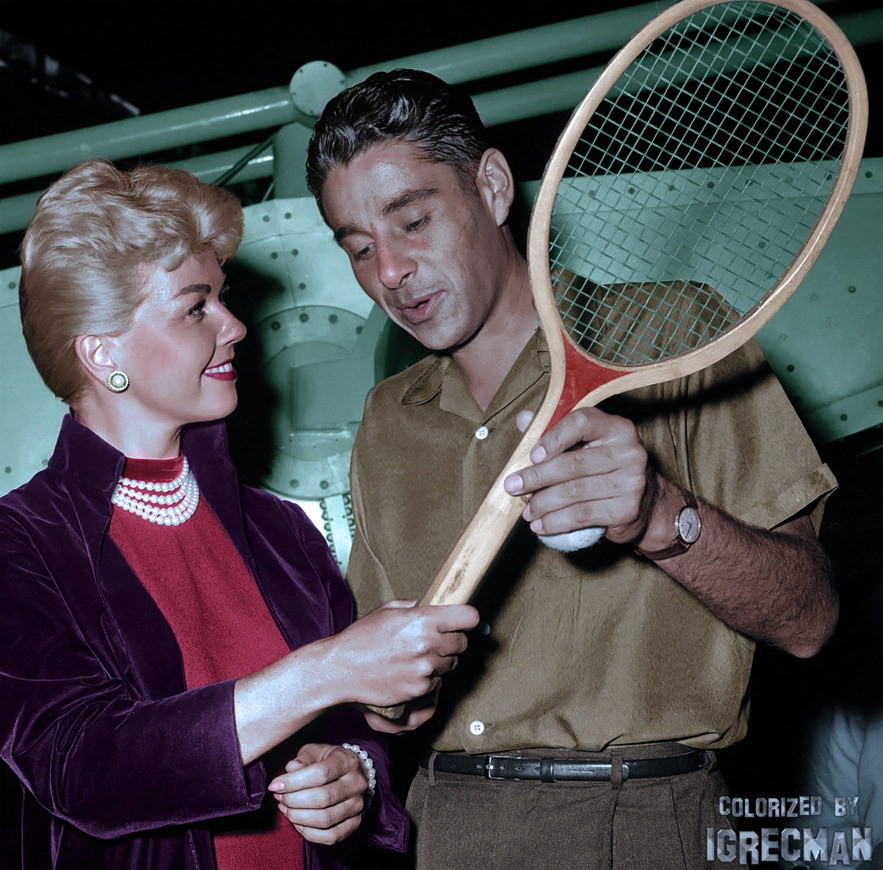

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

When Kramer was 15, he hung around the Los Angeles Tennis Club, picking the brain of Ellsworth Vines and playing practice sets with everyone from Bill Tilden to Bobby Riggs. At the same age, Richard had given up on school. Perry Jones, the man in charge of amateur tennis in Southern California, called González “the most natural athlete I have seen in 33 years at the Los Angeles Tennis Club.” But the dropout didn’t meet Jones’s standards for a young tennis hopeful, so he was banned from tournaments.

As a result, Gorgo didn’t get any high-quality match experience until he was 19 years old. He was discharged from the Navy in 1947. There was no more school for him to skip, so Jones couldn’t block him from tournaments on those grounds. The newcomer entered several events that first year, winning no titles but losing only to strong players such as Kramer, Schroeder, Segura, and Parker.

Unlike Kramer, he wasn’t playing carefully worked-out percentage tennis. He didn’t need to. He served big, and his movement–the most natural gift of all–was flawless. Trabert despised González but couldn’t deny the grace that earned Gorgo so many victories:

The way he can move that 6-foot-3-inch frame of his around the court is almost unbelievable…. Pancho’s reflexes and reactions are God-given talents. He can be moving in one direction and in the split second it takes him to see that the ball is hit to his weak side, he’s able to throw his physical mechanism in reverse and get to the ball in time to reach it with his racket.

Jenny Hoad, wife of Lew, said of her husband’s rival, “I don’t think he ever moved in an unattractive way.”

* * *

These days, we’d see such a package of talent and dream about the double-digit majors the man would ultimately pile up. We’d acknowledge the gaps in his game–shoddy conditioning and indifferent groundstrokes, in this case–and figure he’d sort those out in time.

Commentators on the amateur game barely had the time to think in those terms. González won the 1948 national title at Forest Hills, then after several months as the “cheese champion,” he defended his title against Schroeder. Schroed was the favorite, especially in the eyes of Kramer and Riggs, who aimed to sign him up as the next challenger for the pro tour. But Schroeder didn’t really want to go on a year-long barnstorming tour, and his loss to Gorgo deflated his value. Barely a year after bursting onto the national scene, González stepped into the breach and turned pro.

He wasn’t ready, as we’ve seen. But he was paying attention. Kramer noticed him improve throughout that first tour. And somehow–still without any coaching to speak of–he converted himself into the best player in the world in the three years that followed.

Kramer considered him to be one of just three guys–along with Rosewall and Segura–who got better after they turned pro. Segura said as late as 1957, “He can still improve a lot, but I can’t. I’m already doing my best.” Many players who rise on the top on raw talent never plug the gaps. Unaided, González did.

He played little competitive tennis from 1951 to 1953. In two trips to Europe, he won a handful of pro titles, including the 1952 London Pro where he beat Kramer in the final. Most pros never made more than a handful of lengthy tours; after losing to the champion, they’d find a nine-to-five and limit themselves to occasional tournament appearances. But Gorgo wasn’t the office-job sort.

“When I find out they’re lining up a pro tennis tour,” he said in 1955, “I know I’m the guy that has to play in it.”

* * *

Kramer retired after a successful series against Sedgman in 1953. His body was breaking down, and he was ready to shift to the management side of the tour. Without a reigning champion, and with no superstar ready to make the transition from the amateur game, he had to change the formula.

The result was a four-man tour featuring Sedgman, Segura, 38-year-old Don Budge, and González. Gorgo won 30 of 51 matches against Segura and defeated Sedgman by the same margin. (Budge was no longer a factor, and he left the tour early.) Between his performance on the road and two major tournament victories, he was clearly the top man on the circuit.

Fans, then and now, have struggled to follow and understand the pro game in the years before the Open era. Bud Collins called it “the nearly secret pro tour.”* Speaking in the context of González’s legacy, Andre Agassi acknowledged, “The history of tennis is pretty complex.”

* Kramer and his promotional staff would’ve been mortified. Or maybe just outraged. Nearly secret? Despite lacking the cachet of Wimbledon or Forest Hills, news from the pro tours was in the papers constantly. Whenever an editor had a column inch to spare, he was sure to find a Kramer press release ready to fill it.

But like the amateur game with its European clay circuit, British grass-court swing, and North American summer, the pro season had a rhythm. Most years, the major tour began in December, usually at Madison Square Garden in New York. It extended for one hundred nights or more, first criss-crossing North America then heading further afield. The professional “majors” followed in summer. While they could usually boast the full roster of stars, they were not as crucial in determining the pecking order as the marathon barnstorming tour that started the year.

With that in mind, let’s review Gorgo’s performance in his peak:

1954: Four-man tour. Defeated Sedgman and Segura.

1955: No traditional US tour. González went 35-11 to win a multi-player series in Australia against Sedgman and Segura. He was also undefeated in tournament play, including the one-serve, ping-pong-scored US Pro.

1956: The champion took on Tony Trabert, winner of three amateur slams in 1955. González won, 74-27.

1957: This year’s challenger was Ken Rosewall. González took 50 of 76 matches. “My timing?” Rosewall said to a reporter, after one of those losses. “I had no time for timing.”

1958: Fresh off a landslide victory at Wimbledon in 1957, Lew Hoad received a record $125,000 guarantee to go pro. Even after Kramer and Segura coached the challenger to prepare him for the showcase tour, González defeated him, 51-36.

1959: Without a viable new challenger, the tour returned to the four-man format. González won only 13 of 28 matches against Hoad, but his record against Ashley Cooper and Mal Anderson ensured that he kept his title.

1960: Another four-man tour. González allowed Rosewall just five victories in 25 tries. The newest addition to the troupe, 1959 Wimbledon champ Alex Olmedo, fared even worse.

1961: Gorgo won a several-player series, then took 21 of 28 matches against runner-up Andres Gimeno to retain his crown.

González, now 33 years old, took most of the next two years off. Still, he couldn’t stay away. Between 1964 and 1967, he won 4 of 13 meetings with Rosewall and 12 of 33 against Rod Laver, who was ten years his junior.

* * *

Life on the pro tour embittered the champion. The initial series against Kramer taught him just how little room there was at the top. When he took over as champion, he griped about money. Kramer believed that amateur champions like Trabert and Hoad were the draw, so González, as the veteran pro, was paid less than some of the men he beat.

When he won his first national championship, Life magazine described him as “happy-go-lucky.” A decade later, he was barely on speaking terms with many of his opponents. On a bad day, he’d bark at linesmen, photographers, even an overenthusiastic fan in the grandstand. He avoided the press and rarely signed autographs. While the rest of the troupe banded together to make the best of a lonely existence, González drove by himself from one tour stop to the next.

Yet by the time Open tennis arrived, Gorgo’s stature was such that it didn’t matter. The old man–he turned 40 in 1968–was an enormous draw. More remarkably, he could still compete with the best players in the game. He not only qualified for a 1968 year-end event featuring the top eight pros in the game, he reached the final.

Even his opponents could appreciate the legend in their midst. Denmark’s Torben Ulrich lost to him in five sets at the 1969 US Open. “Pancho gives great happiness,” he said. “It is good to watch the master.”

González had turned in his most memorable performance two months earlier, at Wimbledon. He drew another big server, 24-year-old Puerto Rican Charlie Pasarell, in the first round. The two men traded holds for a whopping 45 games before Pasarell secured the first set, 24-22. In the fading light, González hounded the referee to suspend the match. Play continued anyway, and he tanked the second set. He went home for the night in a two-set hole.

Gorgo had lost the crowd with his carping. But when the players returned the next day, he knew he could outhit the youngster. He secured the third set in another marathon, 16-14, then took the fourth, 6-3. Pasarell ultimately earned seven match points, but González fought them off, one with a stunning drop volley.* After more than five hours, the veteran pulled out the fifth set, 11-9, in what was then the longest match in grand slam history.

* The champion loved that shot: “It may have looked great to the crowd, but it was bread and butter to me.” I can’t help but think of Miles Davis on his final tour. “Aw, man,” said Miles as the applause finally died down. “I do that every night.”

Even away from the one-on-one, pro tour format where he fought like a heavyweight champion, González had a way of turning tennis into a duel to the death.

16-year-old Vijay Amritraj, years away from his own pro success, skipped meals to buy a ticket and watch González play that day. “He lived up to my dreams,” Amritraj said. “I still don’t see anybody who devoured the sport as he did.”