I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. Beware of GOATs.

* * *

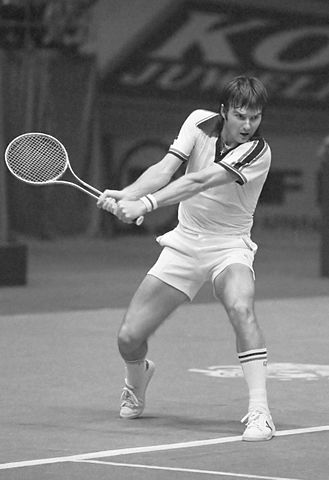

Jimmy Connors [USA]Born: 2 September 1952

Career: 1971-92

Played: Left-handed (two-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1974)

Peak Elo rating: 2,364 (1st place, 1979)

Major singles titles: 8

Total singles titles: 109

* * *

Few men have ever approached the longevity of Jimmy Connors. He reached his first Wimbledon quarter-final in 1972, when he was 19. He thrilled New York crowds with his most memorable performance, a semi-final US Open run in 1991, the week of his 39th birthday.

He won 1,274 matches and amassed 109 tour-level titles. Both have stood as Open era records for thirty years. With Roger Federer’s retirement, they may last another thirty. Rafael Nadal, currently the active leader in matches won, needs another 208 to catch up.

You’d think 1,274 victories would be enough. Yet there are still more that don’t count toward the official tally. To me, two of those unofficial matches are the best exemplars of the peak Connors experience–his capabilities, his attitude, his appeal to millions of fans amid America’s 1970s tennis boom.

Jimbo, as much as any superstar of his era, padded his bank account with exhibitions. Except not all of these clashes were casual hit-and-giggles. In 1975, his manager Bill Riordan–son of a boxing promoter–hit on the idea of a “Heavyweight Championship of Tennis.” No mere tour stop could contain the ballyhoo of a Riordan production. Whenever Connors played at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, it was a one-off of epic proportions, a prizefight from the baseline.

The two “challenge matches” Riordan staged in 1975 set a new standard for tennis spectacles. Two years after the Billie Jean King–Bobby Riggs Battle of the Sexes, television networks recognized the enormity of the potential audience for tennis. CBS ponied up $650,000–about $3.5 million in today’s dollars–for rights to the second of the pair. Much of that money went straight to the players.

Riordan, with his unorthodox background, might have been the only man in tennis capable of dreaming up such a thing. While Connors was hardly the only drawing card in the game, he was the sport’s biggest name by early 1975. Jimbo won three of the four majors in 1974. (He didn’t play the French Open.) At Forest Hills, he brushed aside Ken Rosewall in the final, 6-1, 6-0, 6-1. He stepped on court 100 times that year, and only once did he lose in straight sets.

There was just one question mark regarding Connors’s supremacy. He was the only top player who skipped Lamar Hunt’s World Championship Tennis (WCT) tour. Instead, he played a Riordan-managed circuit of minor events. In February, Connors won a cheap title in Birmingham, Alabama. The same week, Arthur Ashe, Björn Borg, Rod Laver, John Newcombe, and Stan Smith duked it out at WCT events in Long Island and London.

But Riordan could play that to his advantage, too. His client remained an unknown quantity. Even as Jimbo put the finishing touches on his third major title, he had yet to face many of the top players in the game.

Connors knew what he had to do to prove that he deserved to be number one. After clobbering Rosewall at the US Open, he had three words for his manager.

“Get me Laver.”

* * *

Okay, maybe that’s what he said. It’s too good to be true, right? And anyway, who says that after a match? That’s not how tennis works.

Gene Scott, a former American top-tenner and magazine publisher writing in the New York Times, was certain: “Of course, Connors said no such thing.” Many in the press corps were willing to believe he said it–but only because Riordan coached him ahead of time.

Jimbo himself insists it was spontaneous. It makes for a good story, anyway.

No matter what Connors uttered in his moment of triumph, the match was on, set for a purpose-built arena at Caesars Palace on February 2nd, 1975. There was even a backstory to justify bad blood between the two. Laver, the 36-year-old who had won the Grand Slam in 1969, said in early 1974 that Jimbo “probably thinks he’s the next best thing to 7-Up.” Not exactly Don King, but you weren’t likely to get the Australian gentleman on record with anything spicier than that.

Riordan billed the first challenge match as a $100,000, winner-take-all showdown. In truth, there was little at stake except for pride. Both players got substantial guarantees. The manager gave Laver sixty thousand reasons to make the trip to Vegas.

No one would ever mistake Rocket Rod for a pugilist, but Connors played his own part to a tee. With Riordan, mother Gloria, and coach Pancho Segura in tow, he bickered over the balls, the umpires, the ground rules–anything to fuel the fire and, not coincidentally, feed the press. He went on court with a custom-made warm-up jacket emblazoned with his catchphrase for the day, “Better Than 7 Up.”

* * *

Jimbo’s preparation for the match reflected his sky-high confidence. He told the Times two weeks before the big day:

I’ve never played Laver, in fact I’ve never really watched him play. When he won the Alan King tournament in Vegas last year, I watched him play two games on TV, then I turned it off. I’m not one for watching.

It hardly mattered. In his corner was Segura, one of the smartest tacticians in the game. Pancho was always watching. The old pro advised Connors to attack Laver down the middle and to minimize the impact of the Aussie’s heavy topspin by moving forward at the first opportunity.

Segura got into the spirit of the spectacle, too. He probably had money riding on his pupil; at the second challenge match later in the year, rumor had it that he bet $11,000 on Jimbo. As the players took the court, he passed on his final advice: “Kill him, kill him, kill him!”

Connors needed little urging. The prime $100 seats were packed with Laver supporters, celebrities like Johnny Carson and Clint Eastwood among them. The American revved himself up further, yelling “Fuck you! Fuck you!” to the glitterati.

The clash wasn’t sanctioned by any tour, but this was no exhibition.

Laver said, at least for public consumption, that his advanced age was no hindrance. He trained hard, won a tournament in preparation, and felt he could go toe-to-toe with the 22-year-old for a single match. On the day, though, it took him two sets to get going. Connors took the first two sets, 6-4, 6-2, following Segura’s game plan and neutralizing the Rocket’s serve with his aggressive, flat returns.

The Australian found his groove in the third. He got on the board, 6-3, as his deep forehands found the range. On the offensive, he could show off the variety that once made him the best player in the world. The men traded holds for the first nine games of the fourth set. With Laver serving at 4-5, they played a single game that nearly justified their paychecks. Rodney’s fifth hold of the set required 22 points. He saved five match points, two of them with clean aces.

Finally, the age difference told. Laver was spent, and Connors was as fresh as ever. At 5-6, Jimbo broke to love. The match was his.

* * *

August sportswriter Red Smith called it “the most grossly opulent match ever played.” Riordan called it a job well done. Connors–not to mention the good folks at CBS–agreed.

Connors said in 1978, “I peak every time I play.” He was indeed the king of his realm. He wouldn’t lose a match until June. But he always soared to his greatest heights when he had something to prove.

Conveniently enough, Jimbo had started his 1975 season with a loss at the Australian Open. His conqueror there was John Newcombe, another veteran Aussie, a mustachioed six-footer with an arrogance to match Connors’s own. Who better for the American to battle in Heavyweight Championship II: Electric Ballyhoo?

The Laver match established that the audience was there. Now Riordan and his client really cashed in. Connors-Newcombe was billed as $250,000, winner-take-all. In fact, both players took home more than that. Newk even juiced the match for a bit of extra promotion. The ball kids sported his own clothing line.

The sequel was just as serious as the original. As soon as the date was announced, fans told Newcombe, “I don’t want you to beat him, I want you to kill him.” The Aussie was puzzled by the animosity. He put it down to Connors’s refusal to play Davis Cup for his country. After all, the Laver match had taken place the same weekend that a lackluster United States side lost to Mexico. One of Riordan’s many feuds was with the men in charge of the Cup squad, so avoiding such a scheduling conflict was never a concern.

For his part, Newk recognized that the rewards were ridiculous, the incentives out of whack. There were no ranking points to earn, and tennis had already made him a rich man. “You want to win a match like this,” he told Leonard Koppett of the New York Times, “because you want to be the winner.”

Hard to argue with that.

* * *

Laver-Connors was a match of contrasts. While both men were left-handed, it was a clash of age versus youth, variety versus brute strength, netrushing versus passing shots.

The second showdown at Caesars Palace was power versus power, a monster serve against the sport’s most devastating return. Newcombe had one of the most ferocious attacks in the game. Segura told Jimbo to take advantage of Newk’s size and middling movement by hitting low backhand slices.

The pre-match machinations were, if anything, even more convoluted for the second challenge match. Connors came down with mononucleosis the month before. As the date approached, he needed live tournament practice. Newcombe was scheduled to play a WCT event in Denver the week before Las Vegas, and he thought the sides had agreed that Connors would stay away. Jimbo disagreed. As a last-minute entry, the number one player in the world went through qualifying and won the tournament. Newk withdrew.

It was a promoter’s dream. One of the contenders had fled in fear of the other.

The Australian was more annoyed than afraid. It probably didn’t matter. Regardless of his mood, he wasn’t strong enough to beat Connors. He served big for two sets, putting something extra behind his second serves, but that only earned him a split. He didn’t have any more in the tank, and Jimbo cruised to victory, 6-3, 4-6, 6-2, 6-4.

“Serving to him is like pitching to Hank Aaron,” said Newcombe after the match. “If you don’t mix it up, it’s going out of the ball park.”

* * *

After Connors beat Newcombe, Leonard Koppett explained what he saw as “the limitation of challenge matches: matches like the one with Laver don’t come up frequently.” The traditional tour structure had the advantage: “[I]n regular tournaments at least there is a context.”

What Koppett missed–understandably, since the tennis world was still coming to grips with the young Connors–was that Jimbo was the context. The street-smart underdog, the scrappy counterpuncher, the unlikely champion with a signature strut could draw enormous crowds without any need for a historic venue, or even a worthy foil.

Problem was, the Jimbo-versus-the-world model laid an enormous amount of pressure on the hero. After putting an exclamation point on his number one position by beating Newcombe, his motivation sagged. He put on weight and took advantage of the social perks available to a celebrity like himself. He couldn’t help but play the underdog, and it was more comfortable to do that without also reigning over the entire circuit.

Circumstances sped his descent to mere almost-greatness. He lost the 1975 Wimbledon final to Arthur Ashe, a veteran he had beaten in three previous encounters. Segura stayed home–a result of a spat with mother Gloria–and Connors hyperextended his knee in the first round. The injury got worse throughout the fortnight. At a lesser event, he would have withdrawn. His defeat was understandable, but his perch at the top was punctured nonetheless. The man who had pasted Rosewall, Laver, and Newcombe was no longer untouchable.

By the end of the year, Connors had lost to Vijay Amritraj, Eddie Dibbs, Adriano Pannatta, Raul Ramirez, and Manuel Orantes. The Orantes match was a particular disappointment: It was the Forest Hills final, a match he suddenly couldn’t muster the discipline to win.

The good news? Losing to Orantes gave Riordan an excuse for another challenge match. Back in Vegas in February 1976, Connors obliterated the Spaniard for another (purported) $250,000 prize. The score was 6-2, 6-1, 6-0, and Jimbo proved that on a favorable surface, he was superior to the fifth-best player in the world.

He split with Riordan, but the manager retained the rights to the challenge match concept. Before Ilie Năstase finally beat him in April 1977, Connors won 13 straight matches at Caesars Palace.

* * *

While Jimbo’s career still had 15 years to run, his days at the top were numbered. He held off Björn Borg in the 1976 US Open, but once the Swede caught up with him, Connors managed only two victories in 14 meetings.

According to the official rankings, Connors held on the number one position–with a single one-week break–until April 1979. My historical Elo ratings aren’t so rosy. Though Jimbo was always near the top, he split time in the late 1970s with Borg, Ashe, and Guillermo Vilas.

By 1978, fellow players noticed that the American had mellowed. His practice routine also held him back. He was famous for short, high-energy hitting sessions, but all the sweat disguised the fact that he rarely worked on his weaknesses or sparred with his equals.

An unchanging Connors was still plenty good, just not good enough to dethrone Borg at Wimbledon or, a few years later, hold off John McEnroe. He remained a top-five player until the mid-1980s, including a resurgence in 1982 that gave him his second Wimbledon crown.

And finally, 1991. At age 38, he summoned all the wiles, all the daring, and all the sheer stubbornness of his 20-year career to make one last run at the US Open. His first-round match took four and a half hours. His fourth-rounder, against Aaron Krickstein, lasted 4:41. With a computer ranking of 174th in the world, he gutted out a quarter-final against Paul Haarhuis. It’s a cliché to say that Connors played with his heart on his sleeve. That night against Haarhuis, Jimmy’s heart was on everyone’s sleeve.

One last time, as Sports Illustrated put it, “Jimbo was the only thing in tennis anybody cared about.” It didn’t matter that he lost in the semi-finals. When Connors was at his slugging, pugnacious best, you simply couldn’t look away.

New Yorkers claimed the veteran as emblematic of their gritty hometown. But really, Jimbo’s last stand turned every match into a one-night only performance worthy of Las Vegas.