Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. Whee!

* * *

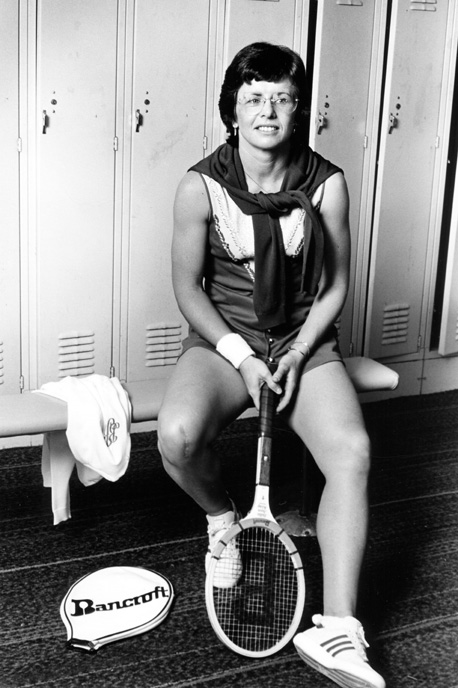

Billie Jean King [USA]Born: 22 November 1943

Career: 1959-83

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1966)

Peak Elo rating: 2,321 (1st place, 1972)

Major singles titles: 12

Total singles titles: 129

* * *

You’ve probably seen Billie Jean King lately. Maybe she was calmly looking on during the US Open, sitting in prime seats at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. Perhaps she had a quick spot on the TV news, explaining her latest initiative. Or maybe she was giving an acceptance speech for a lifetime achievement award. She’s made a lot of those speeches.

There have been several Billie Jeans over the years. You might also be able to picture the 1973 version, or at least Emma Stone’s portrayal in Battle of the Sexes. At age 29, King knew she was fighting battles on a vast scale. She had led the charge for the Open era of professional tennis, and she had threatened to boycott the US Open until it offered men and women equal prize money. When she faced Bobby Riggs at the Astrodome, she felt the weight of half the world on her shoulders.

By then, she wasn’t just a tennis player. She was a symbol. And symbols are serious.

Billie Jean was always serious, but not world-historical serious, not New York Times op-ed page serious. She fed on pressure. She lived to compete. Her campaigns for equal rights and recognition eventually took center stage, but for a decade, winning came first. She knew she had it in her to become a champion, and by god, that’s what she set out to do.

The only obstacles in her path were the standards of her era. She married young, and for a few years she played tennis only part time. It is particularly jarring to see headlines from the mid-1960s shouting that King might give up the game if her husband asked. Billie Jean and Larry King were mismatched in many ways, but ultimately, they agreed on one thing. If someone has the potential to become the best in the world at something, she ought to pursue it. Odd as it is to say about a gay icon, Billie Jean King married the right man.

* * *

Frank Brennan, one of King’s early coaches, once listed his student’s assets. Number one: “Singlemindedness.”

Nice as it was to have Larry’s support, it was even more important for Billie Jean to establish in her own mind that she could discard everything that wasn’t tennis. She told Frank Deford in 1975:

I was brought up to believe in the well-rounded concept, doing lotsa things a little, but not putting yourself on the line. It took me a while before I thought one day: who is it that says we have to be well-rounded? Who decided that? The people who aren’t special at anything, that’s who.

For the young tennis player, that meant she could abandon her studies and spend long spells away from home and husband. This shift in mindset is generally dated to late 1964, when the 21-year-old Billie Jean went to Australia to work with Mervyn Rose.

While the trip marked a new focus on the game, it’s easy to overstate how much of a gamble it was. She won the Wimbledon doubles championship with Karen Hantze on her first trip to the tournament in 1961. A year later, she upset top-seeded Margaret Smith (later Court) in the second round, and she reached the title match in 1963. By the end of that season, according to my historical Elo ratings, she was one of the top five players in the world.

Billie Jean at Wimbledon in 1962

Plenty of work remained. Smith was just one year older, and she was improving rapidly, too. Between Billie Jean’s upset in their first meeting and her 1964 Australian trip, Smith beat her five times in a row. The rangy Aussie would add another three victories during the 1964-65 swing Down Under.

Rose helped King rework her serve, a crucial step in the development of her relentless serve-and-volley game. Exposure to an Australian-style fitness regimen was also valuable. Time magazine had called Billie Jean “the chunky, bespectacled little Californian” in 1962, and it would never be easy for the self-proclaimed “sugarholic” to stay in fighting form.

* * *

Billie Jean’s singlemindedness might imply a tennis-playing automaton, a dullard who thinks of nothing beyond her shaky down-the-line forehand.

Hardly. Crowd-pleasers in the amateur era were often willing to sacrifice competitive fire for showmanship. King proved you could have it both ways. The New York Times wrote in 1963 that she was “the liveliest personality to hit the international circuit in years. She has courage and she has color.”

More a decade later, Deford put it simply: “What fun she is!” The sportswriter was struck by her unflagging enthusiasm and positivity about everything she encountered.

Once she got going, she was the easiest interview in the business. Grace Lichtenstein caught up with her after the 1973 Wimbledon final. Billie Jean “giggled like an insane eleven-year-old” as they drove away from the scene of her victory.

[S]he bubbled like a percolator, talking the way she played–fast, instinctively, the words running together, the ideas bouncing scatter-shot from one subject to the next, her light-blue eyes staring with a near-hypnotic urgency. … Listening to her, I felt as if I were watching a manic Aimee Semple McPherson* on an amphetamine high.

* This was a dated reference even for 1973. Allow me to burrow down this rabbit hole until we get back to tennis. McPherson was a celebrity evangelist before World War II and the model for the character of Sharon Falconer in Sinclair Lewis’s novel Elmer Gantry. Before Lewis took on fundamentalism and won a Nobel Prize, he ghost-wrote 1912 and 1913 United States champion Maurice McLoughlin’s book, Tennis as I Play It.

King was so focused on the court that she could seem unglued off of it. 1970s tour player Julie Anthony told Lichtenstein, “I have heard Billie Jean at times just absolutely babble incoherently.”

* * *

Everything came together for King in 1966. After losing to the young and equally colorful Rosie Casals to start the season, Billie Jean ran off 41 straight victories. She took the US National Indoor title in Boston, then went to South Africa where she recorded her first win against Court in four years. She even threw in a clay-court title at an invitational event in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The streak reached its apex at Wimbledon. King met Court again in the semi-finals. She didn’t just beat her. She did it in straight sets, and she made it sound easy: “Just chip the ball back at her feet.” A three-set victory over Maria Bueno secured her first Wimbledon singles title.

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

The galleries at the All-England Club loved her. They had supported the stubborn, animated underdog since she first upset Court back in 1962. No one ever forgot the experience of seeing Billie Jean in a tight match. When she wasn’t staring down a linesman, she was barking at herself: “Hit the ball, you big chicken!”

Or, in extreme duress: “Peanut butter and jelly!”

The only thing King ever did to alienate the Wimbledon faithful was to win too much. It’s hard to back an “underdog” when she’s finishing up a 6-0, 6-1 rout of Evonne Goolagong, as she did in 1975 for her sixth singles title.

In 1976, Billie Jean was (temporarily) retired from singles. She held 19 career Wimbledon titles, a tie with pre-war standout Elizabeth Ryan, so she was back to enter both doubles events. In the second round of the mixed, fans got behind the South African pair of Bob Hewitt and Greer Stevens, a longshot to knock out King and Sandy Mayer. At one point, the crowd groaned at a line call that went to the Americans. Billie Jean hammed up her disappointment, flopping down on the court before delivering her next serve. She lost the match but won back the crowd.

(History has not been kind to the spectators who cheered for Hewitt, now a convicted rapist, over Billie Jean effing King.)

King finally surpassed Ryan for the all-time record in 1979, when she partnered Martina Navratilova for her 20th Wimbledon title. She would sit atop the list for 24 years, until Navratilova herself equaled the mark in 2003.

* * *

By the end of 1966, Court had stepped away from the game. King was the undisputed number one, despite a shock second-round loss at Forest Hills.

Now Billie Jean was free to start speaking out. While she had “opinions on just about everything,” according to Sports Illustrated, her first signature issue was open tennis. Everywhere she looked, she saw hypocrisy: well-heeled players who pretended tennis was a part-time lark; top men players with no-show jobs; Europeans who collected so much expense money that going pro would mean taking a pay cut; tournament organizers who collected gate receipts then pinched pennies when it came to compensating star attractions like herself.

“What they ought to do,” she said in 1968, “is throw out all the officials and start again.”

In 1967, King won the triple–singles, doubles, and mixed–at both Wimbledon and Forest Hills. She was the best player in the world, yet the only reason she could get a credit card was because of Larry’s career prospects as a law student.

Everything changed in 1968, and Billie Jean was at the forefront. She signed a two-year, $80,000 contract to headline the women’s portion of a professional troupe organized by George MacCall. King, Casals, Ann Jones, and Françoise Dürr would compete alongside long-time pros such as Ken Rosewall and Richard “Pancho” González. In between tour stops, they could enter grand slam events, which were finally open to both amateurs and professionals.

At the first Wimbledon with prize money, King won her third straight title. She nearly matched the feat at Forest Hills, coming in second to Virginia Wade at the inaugural US Open.

* * *

Billie Jean was well on her way to becoming a symbol. Summaries of her career after the dawn of the Open era tend to shift their focus to accomplishments on a larger scale, feats that can’t be measured in rankings or titles.

In 1970, she and Casals double-defaulted at the misogynistic Pacific Southwest, then launched the women-only Virginia Slims tour. In 1973, she proved that a top woman could beat the pants off of a 55-year-old male hustler. In 1974, she introduced World Team Tennis, her attempt to take the sport out of country clubs and give it to the masses. In 1975, she signed a two-year, $200,000 contract to do television work for ABC.

For someone who was so much bigger than tennis, she still played an awful lot of tennis. Injuries slowed her down in 1969, and Court hogged the laurels when she won the Grand Slam in 1970. In 1971, though, King played more than 125 singles matches–winning 113 of them–as she headlined the nascent Slims tour.

If Billie Jean weren’t so famous for everything else, we’d spend a lot more time talking about her 1972 season. After an indifferent start, she rounded into form in April, winning consecutive tournaments on outdoor hard courts, indoors on Sportface, and then the big one, on clay at Roland Garros. She defeated Goolagong in the Paris final, her sole career title there.

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

King beat Goolagong again for the championship at Wimbledon, and she ousted Court in the US Open semi-finals before coasting past Kerry Melville for the title there as well. She won three-quarters of the Grand Slam, and as far as Billie Jean was concerned, that was all that mattered. “I could have won the Grand Slam,” she wrote, “but the Australian was such a minor-league tournament at that time.”

(Translation: They offered me more money to play in New Zealand.)

Measured by wins, 1972 didn’t quite stack up with the marathon 1971 campaign. By winning percentage, King had several better seasons. But the three major titles put her back at the top of the rankings. She defeated Court in three of five meetings, once each on grass, clay, and hard. As Billie Jean tirelessly promoted the tour and began converting her multitude of opinions into concrete causes, she somehow also psyched herself up for victory 88 times.

* * *

King set herself on the path to greatness when she realized she didn’t need to be well-rounded. Her ability to focus never wavered. “I’m used to working hard, giving 100% to whatever I do,” she said in 1976. “I don’t know any other way.”

Except, obviously, she took on more responsibility than any star player in the history of tennis. She gave 100% to her game, 100% to the Slims tour, 100% to the circus with Bobby Riggs, 100% to World Team Tennis, and on and on.

Credit: Lynn Gilbert

The day after beating Riggs in the highest-stakes match of her life, in front of 30,000 fans, she won her quarter-final match at the Virginia Slims of Houston.

The day after.

In 1984, King mused:

My only regret is that I had to do too much off the court. Deep down, I wonder how good I really could have been if I [had] concentrated just on tennis.

It’s a fair question. Margaret Court (among others) might not like the answer. I suspect, though, that the white lines of a tennis court never could have contained all of Billie Jean’s energy. She may not have given 100% to the sport, but she came closer than most. No one has ever put more into her game while simultaneously changing the world.