Credit: James Phelps

I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. Whee!

* * *

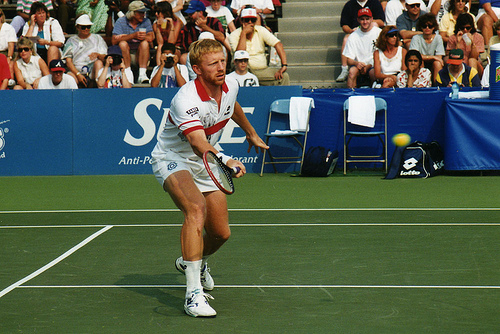

Boris Becker [GER]Born: 22 November 1967

Career: 1984-99

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1991)

Peak Elo rating: 2,320 (1st place, 1989)

Major singles titles: 6

Total singles titles: 49

* * *

Everything Boris Becker has ever done, he has done big.

When Becker appeared at Wimbledon as a 17-year-old in 1985, he didn’t just serve warning on the field–he won the whole damn thing. In a third-round nailbiter versus Joakim Nyström, he smacked 37 aces. Against Kevin Curren in the final, he came in behind his serve 112 times, winning 84.

He stayed back once. He won that one too.

French fans took to calling Becker le grand méchant loup, the big wicked wolf. His build–six feet, two inches tall, 175 pounds–wasn’t itself overwhelming. But he carried himself with a domineering swagger long before intimidation became an explicit part of his strategy.

His serve defied description. Electric? Paralyzing? Just plain massive? Arthur Ashe said a month after Becker’s debut Wimbledon title:

There never has been a tennis prodigy this big. Becker’s like a high school junior in the NBA. He isn’t even all there yet, and he scares the hell out of guys with his power. You hate to play against somebody who’s not only good but unpredictable. The guy hits the ball harder than anyone and yet keeps it in play all day.

Boris’s stature wasn’t entirely his own doing. Reaching the pinnacle of the sport ahead of Steffi Graf, he single-handedly resuscitated German tennis. Media coverage was immediate and all-encompassing. By the middle of 1986, 98% of West Germans knew Becker’s name. Only Volkswagen scored higher.

Becker used the whole court

Even after Becker retired, his celebrity was unmatched. One marketing executive compared his fame to that of Michael Jordan in the United States. Relative to his home market, Boris may have been a bigger name.

The attention, and the pressure that accompanied it, became Boris’s dance partner. When he lost, the German media treated it as a disaster. His slumps became epic in nature. On the flip side, his self-confidence transcended tennis. To his detractors, he wasn’t just a poseur; his half-baked philosophizing made him the game’s biggest phony. Even now, he doesn’t do anything halfway. Plenty of athletes have played fast and loose with their finances; Becker got himself sent to prison for it.

But all that came later. In the the mid-1980s, Boris was the man who saved tennis.

* * *

The remarkable thing about Becker’s unseeded run to the 1985 Wimbledon title is how unsurprising it was.

At the Queen’s Club warm-up, the teenage bomber won the title with the loss of only a single set. He knocked out top-tenner Pat Cash in the quarters and made quick work of Johan Kriek in the final. Kriek predicted that the new champion would win Wimbledon, too. No one was quite sure whether he was joking.

Becker’s next match was his All-England Club opener against the veteran American Hank Pfister. Pfister won the first set, then got steamrolled the rest of the way. He called his opponent’s power “frightful.” Pfister didn’t think Becker was ready to win the whole thing. “But maybe so,” he said. “The guy’s got to win it sometime.”

By the semi-finals, the secret was out. Curren won the first semi, then crossed his fingers that fifth-seed Anders Jarryd would emerge as his opponent for the title. Sorry, Kev. The Swede won the first set and forced a second-set breaker. After that, it was all Becker.

Boris was a breath of fresh air in what would otherwise have been a dud of a Championships. Second-seed Ivan Lendl lost to Henri Leconte in the fourth, and both John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors went out limply to Curren. Becker was new, he was exciting, he was loose, and he dominated. Curren said of his conqueror in the final, “He played like it was the first round.”

The young champion made it all look easy. “Boris never thinks about it; he just plays,” Leconte said. “I see his plan. He just hit ball, make winner, win, say thank you and go bye-bye.”

It was almost that simple. He won 25 more matches in 1985 and cracked the top five of the computer rankings by October. He lost to Lendl three times, though it wouldn’t take long before he drew even with the Czech, too. Most important, he won seven singles matches and a pair of doubles rubbers to get West Germany within a whisker of the Davis Cup. He defeated Mats Wilander and Stefan Edberg in the final round, but it would take three more years for the Germans to clear the final hurdle.

* * *

Impressed by the foresight of Kriek, Pfister, and the rest? Let me tell you about Ion Țiriac.

If you’ve been reading this series from the beginning, you know that I never pass up an opportunity to talk about Țiriac. There is simply no one like him. The Romanian was an Olympic ice-hockey player turned national tennis champ. He cobbled together a solid career on the circuit in the 1960s and 1970s by coupling an impeccable work ethic with relentless mind games. He called himself “the greatest player who couldn’t play.”

Țiriac–Count Dracula, the Brașov Bulldozer, Doom Doom to Becker’s Boom Boom–became one of the sport’s canniest tacticians and talent-spotters. He shepherded Ilie Năstase to the top, then guided the careers of Manuel Orantes, Adriano Panatta, Guillermo Vilas, and Leconte. He made himself a behind-the-scenes force in men’s tennis. His unlikely background and unsettling mien only added to his aura. John McPhee wrote, “Țiriac has the air of a man who is about to close a deal in a back room behind a back room.”

Țiriac (left) and Becker. Ion is almost smiling!

Becker reached the final of the US Open boys’ competition in 1984. Țiriac was on hand, of course. So was every other super-agent and wannabe fixer in the sport. But most of them weren’t there for Boris. They were watching to see if a young Australian named Mark Kratzmann would pick up his third junior major. Kratzmann won in straights, and Mark McCormack of IMG signed him.

Țiriac got Boris. This was no consolation prize. The relationship was already in place. The Romanian had been to Leimen, the small town where Becker grew up. He had met the parents. He had charmed–oh yes, the Bulldozer can charm–the whole clan.

“He said exactly what is going to happen,” Becker said of Țiriac. “And it has.”

Becker’s air of intimidation can be traced directly to his manager. Arthur Ashe described Țiriac’s method with promising youngsters:

He always builds on their strengths. He makes them believe that they are the best in the world in at least one aspect of the game and to use that as a force, as intimidation. It was Nastase’s speed, Vilas’s stamina–he convinced Guillermo that nobody could stay out there with him all day–and Becker’s power. Listen to him build his guy up sometime.”

Dracula made it sound obvious: “I tell Boris the game so easy when one is strongest guy in it.”

* * *

For a little while, it remained that easy. In March 1986, Becker picked up his first win in five tries against Lendl, on carpet in Chicago. He brushed aside Lendl again at Wimbledon in a performance so assured it was almost boring. Boris defended his title and lost only two sets in the process.

Lendl was one of the few men on tour who could handle the Becker offense. At their first meeting in 1985, he camped out 20 feet behind the baseline to return serve. But even that wasn’t always enough, especially on grass. “He always has more power than me,” said Lendl a few years later. “He stays back and stays back, and all of a sudden he takes that big swing.”

“If Becker’s playing great,” said Andre Agassi, “sorry, you have no chance.”

Boris finished 1986 ranked second in the world behind Lendl. His star could hardly shine any brighter, and his image was squeaky clean. That was a bonus of the relationship with Țiriac. The Romanian’s shadowy reputation made it easy for the press to pin the negative stuff on him. Astronomical appearance fees? Charging for interviews? Yep, must be Țiriac.

The honeymoon between the German and his fans ended at Wimbledon in 1987. Boris beat Edberg for the seventh time in a row for the Indian Wells title and blasted his way past Connors for the crown at Queen’s Club. But the two-time defending champion fell in the second round of the Championships to 70th-ranked Australian Peter Doohan.

The German media was brutal. With two major titles before his 19th birthday, Becker had set an impossibly high standard. Even though he would reach each of the next four Wimbledon finals, he would never meet the expectations that stemmed from his early success.

On the other hand, the loss humanized him. A few years later, Curry Kirkpatrick of Sports Illustrated built an entire Becker profile around the idea that he was the most gracious loser in the game. He quoted Boris:

On that day I lose, I just realize the other guy was better. I go on. I’ll get him next time. I think one of my strengths is I never get caught up in the hype of how good I am supposed to be. I know I have to work hard to be as good as some others.

Even more impressive, it wasn’t just talk. He complimented opponents after their victories, he showed concern for injured foes, he even stuck around to play doubles after early-round singles losses. The locker room was plenty intimidated by Becker’s power, but the German earned the respect of his peers. Next to the joyless Lendl, the colorless Edberg, or the bratty McEnroe, Becker was the man that everyone wanted to represent the sport.

* * *

While Becker didn’t lose much, he never became an unbeatable force like Lendl or McEnroe at their peak. His run in 1988 and 1989 was as close at it got.

Doohan forgotten, Boris returned to form on the English grass in 1988. He beat Edberg for the Queen’s title then lost to the Swede in the Wimbledon final. He won four of the five tournaments he played the rest of the way–the exception, alas, was a second-round exit at the US Open–and finished the season by straight-setting Edberg to lead West Germany to its first-ever Davis Cup crown.

1989 was even better. He returned to the number two spot in the rankings with a final-round showing in Monte Carlo, and he even came within a set of reaching the championship match at Roland Garros. He beat Lendl and Edberg in succession for his third Wimbledon crown, then outlasted Agassi in a Davis Cup five-setter in Munich.

To this point, nearly all of Becker’s career highlights came on grass or fast indoor carpet. Finally, he broke through in New York, taking his first US Open crown by overpowering Lendl once more. For Boris, it meant he was “a real tennis player”–one who could win on a wider range of surfaces.

Baseline Becker at the 1989 US Open

Becker wouldn’t reach the number one ranking until early 1991, when he scored yet another big win over Lendl for his first Australian Open title. But with the Wimbledon and US Open trophies in his pocket at the end of 1989–plus a successful Davis Cup defense–he had every right to claim he was the best player in the world.

* * *

The German star had just turned 22 years old when he beat Edberg and Wilander for a second Davis Cup title. He was already rich and famous to an absurd degree. It’s easy to imagine an alternate history in which Becker dominates the tour for another five years and piles up a dozen major championships.

The reality was more pedestrian. In the 1990s, Boris had to settle for two Australian titles and another three runner-up finishes at the All-England Club. The 1991 Wimbledon final was particularly galling, as he lost it to Michael Stich, a countryman he considered far inferior to himself.

Becker’s confidence was part of the problem. He was never particularly coachable, and he got worse over time. Günter Bresnik, who joined Becker’s team in the early 1990s, learned that Boris would try something only if he thought it was his own idea. Another man who attempted to tame the beast, Nick Bollettieri, summed it up: “He knew a lot; what he didn’t know, he thought he knew; and he would intimidate people into thinking that he knew it.”

For a year or two, that was good enough. Over a longer span of time, the tour caught up. Becker won three of his first four meetings with Pete Sampras, another player who traded on a big serve and a will of iron. But Pete, like many of the youngsters who weren’t around for Boris’s rise to the top, wasn’t intimidated by the older man. From 1992 on, Sampras won 11 of their 15 encounters, including all three of their clashes at Wimbledon.

Equally frustrating was the German’s futility against Agassi. Becker won their first three matches, and for a time, he was one of the few peers Andre really respected. The relationship soured as the stakes rose. More relevant to their on-court results, Agassi found a gaping hole in Becker’s tactical armor. The German would stick his tongue out a bit before each serve. Andre worked out that Boris’s tongue pointed the direction he planned to serve. He took advantage sparingly, so Becker wouldn’t notice–so sparingly that it’s tough to prove from the record that Agassi even gained an advantage. But the bottom line is clear enough. From 1990 on, the two men faced off 11 times, and Boris won just once.

In one way, Becker’s inability to stay on top of the competition reduces his status as an all-time great. Six slams is nothing compared to what he could have achieved.

On the other hand, it doesn’t matter a whit. Boris will always be the 17-year-old diving in the Wimbledon grass, the golden boy who represented everything that was possible on a tennis court. Twice as many majors wouldn’t have made him meaningfully richer or more famous. He was a giant before he ever heard the names Sampras or Agassi. Even from the inside of HM Prison Huntercombe in Oxfordshire, he remains larger than life today.

* * *