In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

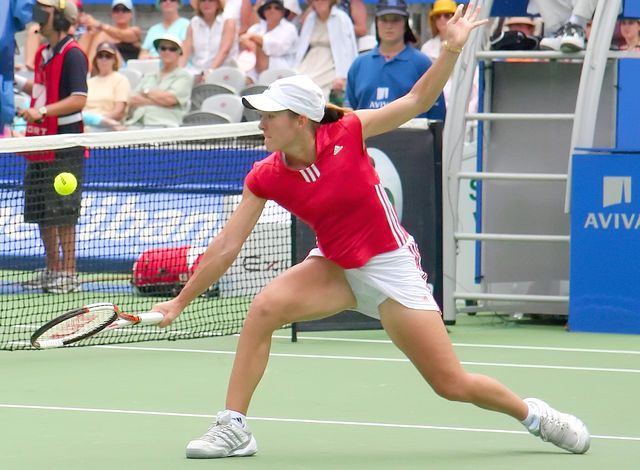

Justine Henin [BEL]Born: 1 June 1982

Career: 1999-2011

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (2003)

Peak Elo rating: 2,437 (1st place, 2007-08)

Major singles titles: 7

Total singles titles: 43

* * *

It didn’t all start with a raised hand, but a raised hand would set off a half-decade of controversy.

Justine Henin trailed Serena Williams 4-2, 30-0 in the final set of the 2003 French Open semi-finals. Serena was the defending champion and number one seed. Henin was ranked fourth at the time; she had won their last meeting, at Charleston several weeks earlier. The Belgian’s main advantage was a raucous, partisan crowd that backed the sort-of local hero in the way that only the French masses can.

At 15-0, Henin missed a forehand long. It was close enough that plenty of spectators disagreed, and umpire Stefan Fransson checked the mark. He confirmed it was out to a smattering of boos and whistles.

When Williams hit her first serve at 30-0, Henin had her hand up, asking her opponent to wait. Fair enough: the crowd wasn’t finished voicing its collective opinion. Serena saw the gesture, missed the serve, then appealed to Fransson for another first serve. He hadn’t seen Henin’s hand, so he looked over at the Belgian for confirmation. Henin didn’t say anything either way. Fransson had no choice but to leave Serena with one serve.

Henin won that point, then the next one, then the two after that. She held serve to tie up the decider at 4-all. The Belgian broke for 6-5 in a ten-point game. With a crafty lob and a pair of big serves, Henin sealed the victory, 6-2, 4-6, 7-5.

Serena broke down in tears after the match. “It wasn’t the turning point of the match,” she said. “I should have still won the game. But to start lying and fabricating is not fair.”

Henin’s reply? “I wasn’t ready to play the point. The chair umpire is there to deal with these kind of situations. I just tried to stay focused on myself and tried to forget all the other things.”

She wasn’t entirely wrong. It is the umpire’s job. But the unwritten rules of tennis assume a reasonable level of sportsmanship. On a scale of 1 to 10, let’s say the acceptable minimum standard is a 3. Justine’s silence on court and buck-passing after the fact rated a 1. Maybe 1.5 if you’re feeling generous.

She continued, “It’s very important to concentrate on the positive things from the match and try to forget this kind of incident.”

It was important for her, yes. She had another match to play, a final against compatriot Kim Clijsters, which she would win for her first major championship.

Henin was able to put the kerfuffle behind her. But her reputation would never recover. In the coming years, she’d add plenty of fuel to the fire. No one would question her grit; even her strongest detractors would gasp at her one-handed backhand. It just seemed that her will to win led her to cross the line.

In some sports, bending the rules to the point of dishonesty is celebrated. Tennis is not one of those sports.

* * *

On a good day, the Belgian was the most thrilling player in the women’s game, a five-foot, five-inch attacker who Martina Navratilova dubbed the “female Federer.” John McEnroe thought her one-hander was the best in the game–men’s or women’s.

Then there were the other days. Her backhand was flashy then, too, but when she offended an opponent, no one talked about her groundstrokes. The 2003 French Open semi-final was hardly Henin’s last offense. Let’s go through the litany.

The Henin backhand in 2002

At the 2003 Acura Classic in San Diego, she lost the first set of the final to Clijsters, 6-3. She then took a five-minute medical time out to change a bandage on her foot. Henin won the next two sets, 6-2, 6-3.

“It’s not the first time she has done this,” said Clijsters. “I think she has probably had to do it in every one of our matches. It’s a sign that she is not at her best and so she has to resort to other means to get out of scrapes.”

Again: completely within the rules. I’m not sure anyone would even notice a five-minute break between sets in 2022. Yet Clijsters was hardly known for complaining about her opponents or making excuses for losses. This particular verbal volley would come up again and again.

The Belgians tried to downplay the nastier side of their personal rivalry. They did not always succeed.

Next up: The 2004 Australian Open final, again with Clijsters. Facing break point at 3-4 in the third, Kim hit a forehand volley that appeared to clip the line. Henin immediately gestured that it was out, and when the line judge didn’t make a call, chair umpire Sandra de Jenken overruled. That gave the break to Justine, and like Serena in Paris, Clijsters crumbled. Five points later, Henin had the title.

This one’s a little more ambiguous. It’s not clear that de Jenken’s overrule was a direct result of Henin’s gesture. It’s annoying when players make their own calls, but it’s not unusual. Without Hawkeye, or at least a much better camera angle, it’s tough to judge.

* * *

Henin missed much of the 2004 season to a virus, and her comeback in 2005 was slowed by a knee injury. Once healthy, she reeled off 24 straight victories on clay, including her second straight Roland Garros title. A hamstring injury slowed her down the rest of the way.

She qualified for the year-end Tour Championships but didn’t play. Pete Bodo spoke for the anti-Justine crowd:

I see this latest development as part of an ongoing saga–that is, Justine doing exactly as she pleases, regardless of all other considerations, and furiously playing the “woe is me” card for all it’s worth. … [T]he greatest danger in down time is that of a player falling irretrievably into the bottomless pit of self.

In case you hadn’t worked out his opinion by then, he called Henin a “demented dwarf.”

That may have been going too far, especially when discussing a player’s decision to rest a recent injury. But Bodo was just getting warmed up. At the 2006 Australian Open, Henin would commit what he called “the most significant and flagrant act of poor sportsmanship I’ve witnessed in nearly 30 years of covering pro tennis.”

This transgression: She retired from the Australian Open final, giving Amélie Mauresmo an abbreviated 6-1, 2-0 victory.

If you weren’t following tennis at the time, it’s hard to grasp the degree to which the tennis world viscerally disapproved. Pam Shriver said Henin’s reputation was “tarnished forever.” Bud Collins–once a sympathetic voice who dubbed Henin “the Little Backhand That Could”–wrote that the retirement left “a bad taste and a blot on the game.”

Henin’s defense: “My energy was very low and my stomach painful.”

That was a tough pill to swallow for a worldwide audience that had watched the Belgian gut out a 32-shot rally–and win it!–four points before walking away.

I’m repeating myself, I know, but once again, Henin was fully within her rights. There’s no law that says that an injured player–however minor the malady–needs to stay on court because of the gravity of the moment, the size of the crowd, or the match point celebration her opponent deserves. But Justine was apparently the only person in the tennis world unaware of the unwritten rule. You just don’t do that kind of thing in a major final.

Henin paid a high price for this one. Five months later, she met Mauresmo again in the Wimbledon final. Maybe the Frenchwoman would’ve beaten her anyway, but the Melbourne retirement certainly gave her an extra bit of motivation.

Wimbledon was the one major title that Henin never won.

* * *

You get the idea. There were another half-dozen minor incidents that reached the press, surely far more that never went beyond locker-room gossip.

At the 2006 US Open, Henin faced Jelena Janković in the semi-finals. She lost the first set and doubled over in pain when she was down a break in the second. From there, Jankovic won–let me check my notes here–zero games. Apparently Justine was okay.

A few years later, Serena Williams apologized to Janković for a mid-match misunderstanding. “I’m not Justine,” she said.

It’s a shame that the tales of rule-bending and poor sportsmanship play such a big role in the Henin legacy. Many all-time greats have seen their accomplishments overshadowed by off-court nonsense simply because of a media narrative run amok. But in the Belgian’s case, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that her determination led her to go too far.

For a rival of Williams and Maria Sharapova, competitors whose will to win could be overwhelming, that’s really saying something.

Henin’s justifications, at least as much as her actions, were what really rubbed some people the wrong way. Pete Bodo paraphrased her mantra: “I have to think about myself right now.” About the controversial line call in the 2004 Australian final: “I needed to take a game.” She didn’t express any sympathy for Mauresmo when she denied her opponent a proper victory in Australia. In all the transcripts and press clippings I’ve canvassed for this profile, I haven’t come across a single sign of sympathy for any of her other victims, either.

Henin propelled herself to the top by seeing herself as the downtrodden one, and for her, that explained everything. In response to the accusation that she faked injury in the 2003 San Diego final, she said, “I think some players don’t like the fact that a player of my stature–less imposing than theirs–is strong and capable of tirelessly running around the court.”

* * *

Her retirement was as puzzling as some of her remarks. Ahead of the 2008 French Open, Henin said goodbye, leaving the game behind when she held the number one ranking and skipping her chance to win Roland Garros for the fifth time.

This time, no one could blame her. She had racked up seven major titles and 117 weeks at the top of the ranking table. Sharapova understood: “If I’m 25 and I’d won [seven] Grand Slams, I’d call it quits too.”

The retirement didn’t stick. Some combination of seeing Clijsters make a triumphant return to the tour and watching Roger Federer win the French to secure his career Grand Slam convinced Justine to give it another go. If Federer did it, maybe she could win Wimbledon and complete her own set.

Henin said of her first time around, to the dropped jaws of the entire tennis world, “Maybe I didn’t fight enough.”

The woman who re-joined the tour in 2010 was mellower, more reflective. “Justine Zen-in,” ventured Jon Wertheim. Her game was as potent as ever. She nearly upset Clijsters in her first tournament back, then beat Elena Dementieva in a nearly three-hour second-rounder at the Australian Open. She reached the final there, where Serena Williams finally stopped her.

Her Wimbledon dream didn’t pan out. She drew Clijsters again in the fourth round, then injured her elbow after winning the first set. There was no faking this time. Henin fractured a ligament and sat out the rest of the season, effectively ending her comeback. She played her last event at the Australian the following year.

Back in 2007, when Justine won her third straight French Open, an interviewer asked her to suggest a nickname. “Queen of Clay is good,” she said. In the sense that she would’ve happily fought her way to the top with violence and palace intrigue–sure, it fits. A benevolent monarch she was not.