In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Fred Perry [GBR]Born: 18 May 1909

Died: 2 February 1995

Career: 1929-47

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1934)

Major singles titles: 8

Total singles titles: 62

* * *

Fred Perry fell one leg short of the Grand Slam in 1934. He beat Jack Crawford at the Australian and Wimbledon, and he outlasted Wilmer Allison at Forest Hills. The missing link was the French. While he would pick up that title the next year, an ankle injury ended his 1934 run in Paris at the quarter-final stage.

The man who benefited from Perry’s injury was Giorgio de Stefani, an ambidextrous Italian who had finished second at the French to Henri Cochet in 1932. In a newspaper column later that year, Perry described the Italian as a “perfect tennis gentleman,” one who rushed to help him up and spared him too much strain on the ankle while closing out the match.

Fifty years later, Perry would tell a different story. He wrote in his memoir that he promised de Stefani an “honorable victory”–that is, he wouldn’t default–but that he asked the Italian not to run him around any more than necessary. De Stefani spoke three languages fluently, but he didn’t get the message. He sent the gimpy Perry scampering along the baseline before polishing off the fourth set and the match, 6-2, 1-6, 9-7, 6-2.

The British champion wasn’t the sort to quickly forget a slight. After the match, he said, “Right, Giorgio, next time we play it’s going to be 6-0, 6-0, 6-0.”

The rematch occurred at the 1935 Australian Championships–ironically, just a month after Perry’s newspaper portrait of the Italian appeared Down Under. They met in the quarter-finals, and Perry delivered as promised. He won 17 consecutive games, fell to 15-40 in the 18th, then recovered to complete the whitewash.

Fred Perry was that good, and he was that confident. It wasn’t the only time he correctly predicted a score, either. Tennis lore is full of tales of the Brit’s bold forecasts. One story has him calling a 6-2, 6-4, 6-4 victory ahead of time–in a Wimbledon final!

Perry made a career out of doing things that just weren’t done. Players–especially British Davis Cuppers–didn’t announce the scores of their matches ahead of time. They didn’t shout “Nuts!” after missing shots–in those days, even that was considered mildly unsportsmanlike. Would-be champions weren’t supposed to come from working-class stock, and they certainly weren’t to act like they did.

The clubbable men behind the scenes at Wimbledon and the British Lawn Tennis Association could never quite hide their disdain of the son of a Labour MP. But fans were a lot more welcoming. After all, Perry did a lot of other things that set him apart. He won Wimbledon three years running. He brought the Davis Cup back to the Isles for the first time since 1912, and he helped keep it there for four years.

If it weren’t for Andy Murray, we’d still be bringing up Fred’s name every time a home hope set foot on the Wimbledon turf. The British waited a long time for a player of Perry’s caliber, and once he left the arena, they had to wait even longer for the next one.

* * *

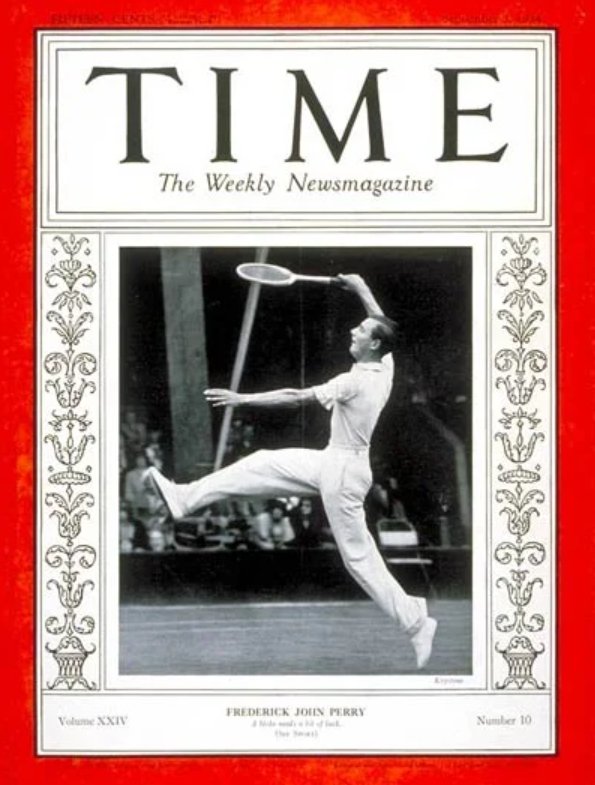

Though Perry was often certain of victory, he was also well-attuned to the vicissitudes of high-level tennis. He told Time magazine in 1934, “In the tennis world, there are about five blokes who are as good as each other. In order to win, a bloke needs a bit of luck.”

The other blokes might have raised an eyebrow at that. Aside from de Stefani, no one but Perry had found much luck that year.

Maybe he did get some breaks, but in the Brit’s view, they were only his due. He explained to the New York Times when he arrived for Forest Hills that year:

It’s always a bit of luck that helps you win, and that’s just what has been happening to me this year. I’m not playing any better than in 1930 and 1931. Then I was losing titles in the fifth set. Now I’m winning them in the fifth.

Wait a second. Perry was an untested stripling in 1930, a 21-year-old table-tennis world champion who had only recently given his full attention to the lawn version of the game. Was this gentlemanly modesty or astonishing confidence?

With the Englishman, it was usually the latter. Still, the young Fred was awfully good. He reached the final at a 1931 clay court tournament at Queen’s Club and lost a 7-5 fifth set to Bunny Austin. He played the cannonball-serving American Ellsworth Vines four times in the United States that year. Twice he lost in five, including in a semi-final at Forest Hills. The one straight-set decision went to Vines in the final of the Pacific Coast Championships, 6-3, 21-19, 6-0. Third set notwithstanding, it was understandable if Perry remembered that one as a marathon that could’ve broken either way.

* * *

Citizens of the tennis world had their eyes on Perry by the end of 1931. In fact, many of them had lost to him personally as the British Davis Cup team romped through six rounds against Monaco, Belgium, South Africa, Japan, Czechoslovakia, and the United States. Perry went undefeated in the first five of those ties, then beat Sidney Wood and watched as Austin played the hero against the Americans.

In the Challenge Round against France, the remaining three-quarters of the Four Musketeers were too strong. Nonetheless, Perry was the story of the conclusive tie. He won a fast-paced, five-set rubber over Jean Borotra and gave Cochet a battle in the decisive match before conceding, 6-4, 1-6, 9-7, 6-3.

The tie at Stade Roland Garros gave a glimpse of both Perry’s present and his future. Borotra, the quickest man in the game, was the player who journalists would most often use as a comparison for the young Brit. Cochet, on the other hand, was Fred’s own model.

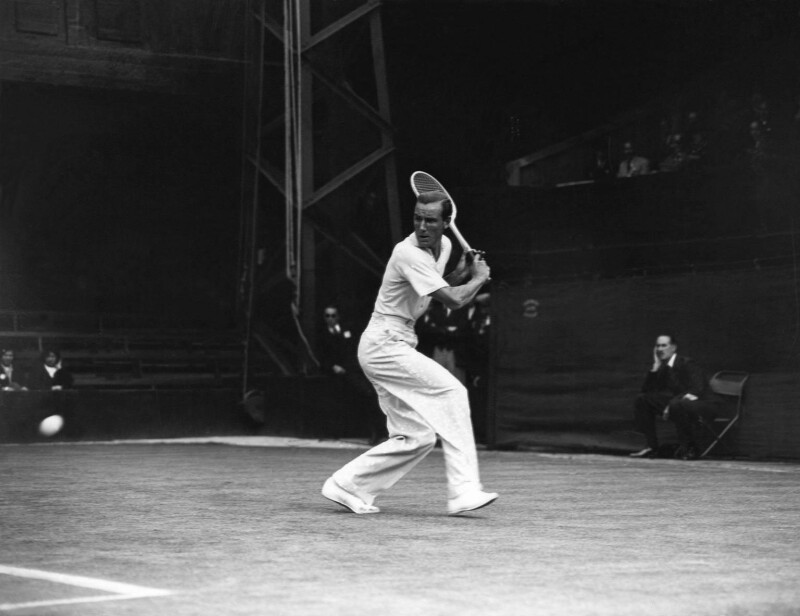

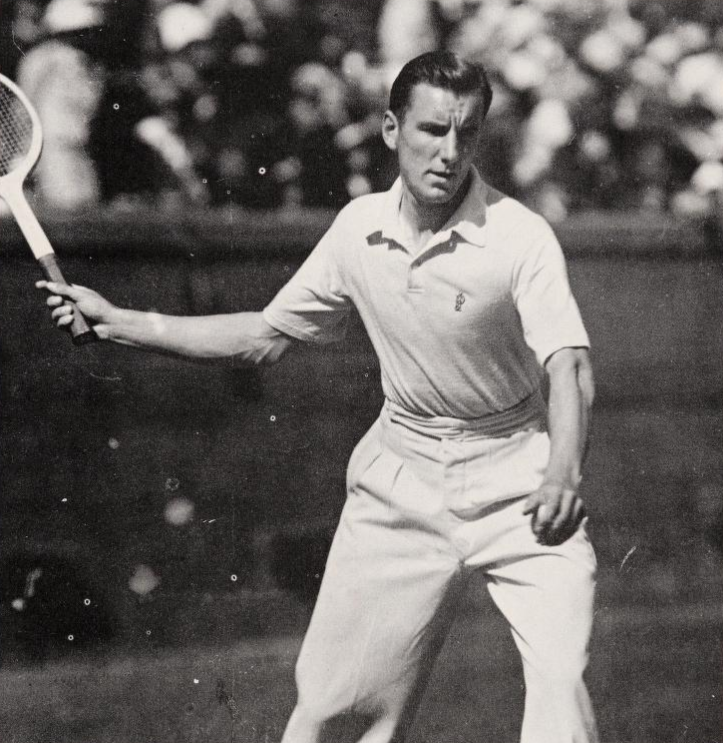

Perry’s table tennis background provided the basis of his lawn tennis game. He had only one grip, an extreme Continental that he also used to chop firewood. His table-honed reflexes allowed him to take almost every ball on the rise, especially on his forehand side. It was the Cochet game, writ larger. “[B]ecause I was bigger, stronger, and faster,” Perry wrote. “I hit the ball harder. [I was able] to carry his methods a stage further than Cochet himself.”

When Fred complained to the Times about the days when luck didn’t go his way, he might have been thinking more of his indifferent 1932 season. The British Davis Cup campaign ended three stages earlier than the year before, when the squad faced Germany in Berlin. Perry trounced Gottfried von Cramm but lost the deciding rubber to Daniel Prenn, 7-5 in the fifth.

Bad luck comes in many forms. Perry held match point on Prenn’s serve at 5-2 in the deciding set. The German hit a serve that Perry slapped back for a winner… or so he thought. But no, the baseline judge had called a foot fault on the home player. Prenn played a better point off his second serve, and the Brit never did win his sixth game.

“How could I have lost five games in a row after having had match point?” asked Perry in his autobiography. “Well, to this day, I still don’t know.”

* * *

Perry wouldn’t have many more such puzzlers in his amateur career. Once his game caught up to his bluster, opponents could only sit back and watch.

Wimbledon player liaison Ted Tinling observed that Fred “was the first Englishman to see tennis as a battle rather than a game.” In retirement, Perry was even more direct: “In any one-on-one sport–take boxing–you go into it expecting to beat the hell out of the other fellow.”

The first victim of peak Perry was, well, everyone who dared to play for the 1933 Davis Cup. In seven rounds, the number one Brit lost only singles rubber–to the pesky de Stefani–and two doubles matches. He took revenge on Cochet on the first day of the Challenge Round, then sealed Britain’s victory with a deciding rubber defeat of the young Frenchman André Merlin.

Cochet sketched the rising star in just a few words: “ruthless, full of confidence, insolent, a rough fighter.”

The French had held the Cup for six years; before that, the United States held it for seven. Neither one would get it back until after Perry turned pro and left the Davis Cup behind.

Confidence begat confidence. In early 1934, a reporter asked “Fearless Fred” how he rated the Americans’ chances. He replied, “Oh, they have a nice doubles team, you know, but really!”

The last domino fell at Forest Hills in 1933. Perry exited early at Wimbledon, a blemish quickly forgotten in the excitement of the Davis Cup. Meanwhile, Gentleman Jack Crawford found himself holding the titles of Australia, France, and Great Britain, raising the question of whether he could complete the newly-named Grand Slam. While the indolent Australian showed signs of fatigue, he progressed easily to the final at the United States Championships, as well. Perry awaited on the other side of the draw.

Crawford took a two-sets-to-one lead in a hard-fought title match. Allison Danzig wrote for the Times:

Even when the Australian was in the plenitude of his powers, however, it was all he could do to hold his swift-moving and sharp-hitting opponent on even terms…. So much depth did Perry have on his shots, so everlastingly was he making the chalk fly on the corners, that the Australian was desperately pressed to keep the ball in play with his more tempered and less daring strokes.

Perry summarized the match more succinctly. When the players returned from the customary ten-minute intermission to play the fourth set, he “went mad.” The Brit won the last two sets, 6-0, 6-1, in less than 30 minutes.

* * *

The match in New York was a coronation. Crawford, great as his season was, didn’t have the makings of a reigning king. Vines, the 1932 Wimbledon champion who nearly defended his title, went pro. Perry kept getting better, and there was no one on the amateur horizon to challenge him.

The British number one would play twelve major tournaments between the 1933 US Championships and the end of 1936. He won eight of them.

The 1934 Australian and Wimbledon championships solidified Perry’s domination of Crawford. The two men contested both finals, and the Englishman didn’t lose a set. At Wimbledon, Perry ran off 12 consecutive games. “If I live to be 100,” he said, “I’ll never play so well again.”

The professional game beckoned. Vines and Bill Tilden were earning movie-star salaries after abandoning the amateur game, and Perry was the next logical target. Fred had no family wealth and no profession except for lending his byline to newspaper columns. His father had bankrolled his career in the early going, and the British LTA had picked up the tab since–though the organization that collected the gate receipts for the Davis Cup Challenge Round was hardly running a charity.

Reporters badgered Perry about his plans. Throughout 1934, he said he had no intention of going pro. The pay-for-play game was an increasingly acceptable option in the United States, but for a Brit, it would mean complete rejection from acceptable tennis society.

What the champion didn’t say is that he had never found English tennis society terribly welcoming. An LTA official once let slip to Fred’s father that they didn’t think of the young man as “one of us.” After his 1934 Wimbledon victory, Perry overheard a club member, Brame Hillyard, tell Crawford that the better man didn’t win that day.

In retrospect, it’s remarkable that Perry stuck it out on the amateur circuit for as long as he did.

* * *

The British number one defended his Forest Hills title in 1934, proving he could win when he was not as his best. Helen Jacobs, women’s victor at the same event, was impressed by Perry’s five-set defeat of Wilmer Allison: “Every characteristic of his temperament, though occasionally annoying to his friends, manifests the assurance of a champion.”

Perry opened the 1935 season on a down note, losing the Australian final to Crawford. Promoters in the United States pushed him to join the pro circuit, and it’s possible that their persistence–including late-night phone calls that were more appropriate for time zones Stateside than in Oz–left Fred ill-prepared to defend his crown.

The early loss didn’t slow him down for long. He won the French to complete his set of titles at all four majors, then defended his Wimbledon title. At both events, he defeated Crawford in the semis and von Cramm in the final.

The German Baron was another “better man” in the eyes of snobbier All-England Club members, but he beat Perry only once in six tries. As Allison said, “von Cramm certainly has the better strokes, but it’s the final score that counts.”

By 1936, it was only a matter of time before the newly-married champion signed a professional contract. He reached the Roland Garros final, obliterated von Cramm for his third straight Wimbledon crown, and edged out Don Budge for the championship of the United States.

Perry was already effectively playing for money in his last major as an amateur. He had agreed to terms with the promoter (and former Davis Cup player) Frank Hunter, including a bonus if he won Forest Hills. Hunter and friends amused themselves during the final by brandishing the larger contract when Perry was winning, the smaller one when he was losing. Two rain delays and nearly three hours of paper-waving later, the Englishman won his eighth and final slam, 2-6, 6-2, 8-6, 1-6, 10-8.

* * *

Perry was only 27 years old when he turned pro. While Budge would’ve made his next Wimbledon campaign considerably more competitive, Fred’s major count probably would have reached double digits.

Instead, he played Ellsworth Vines. Over and over again.

Vines was the reigning pro champion, Perry the challenger. They made a good pair, as the American’s enormous serve and bruising groundstrokes tested Perry’s lightning reflexes and aggressive return game. Fans turned out in droves, and while Vines won 32 of their 61 meetings, the Brit’s efforts in 1937 netted him $91,000–a cool $1.8 million in today’s dollars.

The American won the series in 1938, as well, picking up 49 victories in 84 tries. Perry jokingly characterized American tennis as “B.F. and B.I.–Brute Force and Bloody Ignorance.” But on the fast indoor surfaces that made up much of the pro game, he didn’t have an answer for the more one-dimensional Vines game.

The downside of professional tennis was that it used up amateur champions as fast as Hollywood churned through leading ladies. Even in 1938, the Vines-Perry rivalry didn’t interest the press or the public as much as it had the year before. Budge joined the pro ranks in 1939, and after winning a series against Vines, he took 28 of 36 matches against Perry. The British champion would remain a dangerous competitor in professional tournaments, but when World War II began, Perry’s days as a marquee name were over.

When Wimbledon returned in 1946, the lean years had begun. British fans had waited a decade for a home-grown men’s champion. Their suffering was just beginning. When Perry wrote his autobiography in 1984, it had been nearly half a century. Fred, of course, had an opinion:

There hasn’t been a British Wimbledon men’s champion since me in 1936, and a lot of people keep wondering when we will produce another one. Well, it’s not a matter of producing anybody, to begin with. It’s a case of somebody, somewhere, who wants to succeed badly enough and is determined and bloody-minded enough to make sure he does.

In case that wasn’t clear enough, he added, “Bloody-mindedness was one of my specialities.” He never met Andy Murray, but he might as well have been talking about the man who finally ended the 77-year wait.