In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

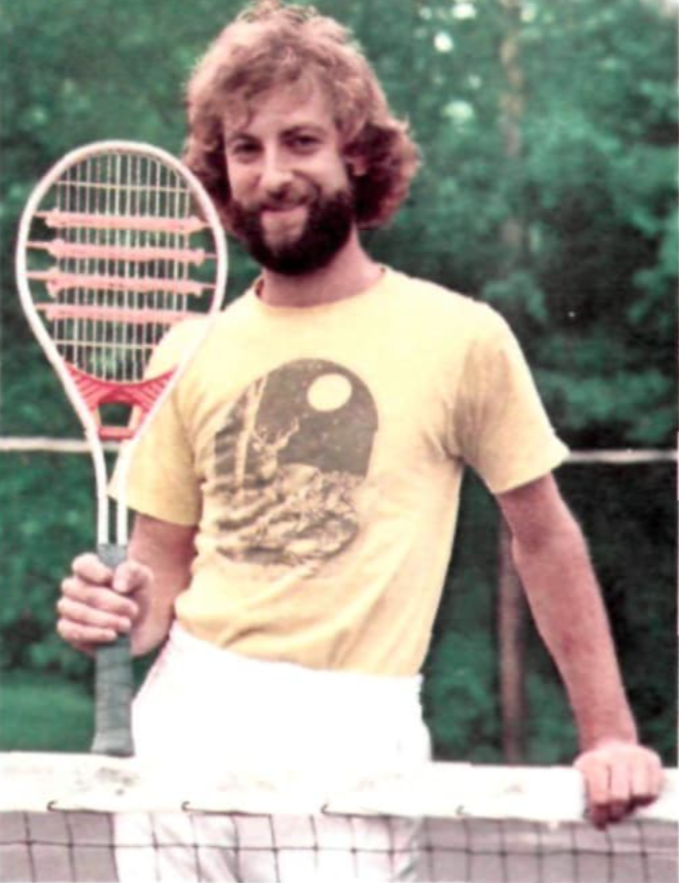

Guillermo Vilas [ARG]Born: 17 August 1952

Career: 1972-88

Plays: Left-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: litigation pending

Peak Elo rating: 2,298 (1st place, 1977)

Major singles titles: 4

Total singles titles: 62

* * *

Was Guillermo Vilas ever the number one player in the world?

It depends who you ask. These days, the ATP ranking formula is the only game in town. You might disagree with its priorities or its conclusions, but the ATP computer is as official as it gets. By that standard, Vilas topped out at number two. At the end of 1977, a season in which the Argentinian dirtballed his way to a 131-13 record and 16 titles, he was still number two. Jimmy Connors held the top spot.

The ATP rankings were only four years old in 1977. For decades, players and tournaments had relied on lists published by journalists, national federations, and various other panels of experts. Those tables didn’t simply go away when the player’s association unveiled its own formula. Most of the pundits looked at Vilas’s record–including championships at Roland Garros and the US Open–and decided that he, not Connors, was the left-hander who belonged at the top of the heap.

It gets even more complicated. In the early years of the computer rankings, the ATP didn’t publish an updated list every week, as they do now. Journalist Eduardo Puppo made it his personal mission to correct the record. With the help of Romanian mathematician Marian Ciulpan, he reconstructed the rankings for those missing weeks. Their work suggests that, had the association bothered to keep the table current, Vilas would have been number one for seven weeks in 1975 and 1976.

The controversy should’ve ended there. Ciulpan’s database of results is at least as complete and accurate as the ATP’s own. His effort to recreate the ranking formula of the time reflects far more diligence than the player’s body ever mustered on its own.

But no. Tennis has rarely left a potential multi-year legal battle unfought.* When Puppo and Ciulpan presented their research, the ATP didn’t refute it. They essentially ignored it. In their record books, Vilas remains outside the coveted number one club.

* The WTA set a better example. Evonne Goolagong was never recognized as number one during her career. When the organization discovered, in 2007, that she should’ve briefly held the position in 1976, they fixed the mistake and have properly celebrated the Australian’s status ever since.

The strange thing about accepting the ATP’s own measurement as gospel is that the measuring stick itself has changed. The association has tweaked its ranking algorithm continually in its 49 years of existence. The formula has changed a great deal since 1977. The current system is additive–that is, players are ranked according to the sum of the points earned in their best 18 events. (Caveat caveat caveat, of course it’s not that simple, but that’s the basic idea.) When Vilas was at his peak, the system was based on an average of points per tournament. That approach tended to favor those who played more limited schedules–and excelled at a few major events–at the expense of those who toiled for more weeks of the year.

If the current formula were applied to the 1977 season, Vilas would look much better. He won two majors, reached the Australian Open final, and won 14 other titles. We could quibble over the details of how that translates into points on the modern scale. Bottom line, it would almost definitely earn him the number one spot. Connors, with his zero-slam campaign, wouldn’t come close. Ironically, Jimbo might fall all the way to third. While Björn Borg didn’t play as much as either man, he won Wimbledon and posted a won-loss record of 75-6.

One more opinion. My historical Elo ratings–the system that comes closest to estimating how well each man was playing and how likely they were to win later matches–concur that Vilas was number one. He earned the spot for one week in 1975, then 31 more weeks between October 1977 and March 1978.

For me, the issue is settled. Vilas was the best player in the world. Knowledgeable fans have thought of the left-hander as number one for 45 years, and the ATP is doing itself a disservice by blocking the Argentine from its most elite club. All that’s left is to shift around a few bits on a database server in Florida.

* * *

All the talk about rankings obscures just how mind-blowing that 1977 season was. Vilas–known all over the world as “Willie”–is the only man in the Open era to ever win 16 titles in the same calendar year. His 131 match victories are also a record. (One source even gives him 139. That might count exhibitions. Either way: He won a lot.)

Between Roland Garros and a tournament in Aix en Provence in late September, the Argentine won 53 consecutive matches on clay courts. He lost the Aix final to Ilie Năstase–in questionable circumstances I’ll get back to in a moment–then ran off another 21 in a row to finish the season.

Reverse the result of the Năstase match, and that’s a 75-match clay court winning streak. It might have even hit 80. Willie pulled out of a Madrid tournament the week after Aix, citing an injury he picked up playing the Romanian.

The only objection one could make to Vilas’s dominance in that stretch is that he generally managed to avoid the other best players in the world. Borg skipped the French Open because he was committed to World Team Tennis*, so the Argentine didn’t meet Borg for his entire streak. They had played twice on clay in April, and Björn won both meetings. Vilas faced Connors only once. At least the South American took that opportunity to make a statement. In the US Open final, he sent Jimbo home in four sets, finishing the job 6-0.

* Yes, WTT was so prominent (read: it paid so well) in the mid-1970s that players were willing to miss Roland Garros.

In the other 73 matches that made up Vilas’s streaks, he defeated anyone who dared show up for an event on dirt. Brian Gottfried was the closest thing the United States had to a clay court specialist. Gottfried reached the French final and took only three games from the Argentine in three sets. Sports Illustrated called him “bewildered.” The pair played two more finals that summer, and Willie didn’t drop a set. Raúl Ramírez, Eddie Dibbs, Roscoe Tanner, Harold Solomon, Wojtek Fibak, Stan Smith, Jaime Fillol… Vilas beat them all.

* * *

He beat them all, except for Năstase. I promised I’d come back to that.

Năstase played the Aix final with a “spaghetti-strung” racket, a twisted, Frankensteinian stringing job that gave its possessor catapult-like power combined with unpredictable, sometimes violent bounces. It wasn’t easy to get under control, but a player who could tame it could drive his opponents nuts.

The spaghetti stringing involved a variety of unlikely materials–nylon, fishing line, and adhesive tape. The process involved doubling the cross strings with the oddball additions. It wasn’t against the rules because at the time, there were no rules governing the nature of rackets and their strings. The evil genius responsible for this was a German horticulturist named Werner Fischer, who ultimately offered both a racket and the off-the-wall stringing job for $100 a pop. German pros generally wrote him off as an eccentric, but he caught the attention of Barry Phillips-Moore, an Australian veteran who took the racket on tour.

At first, Phillips-Moore tried to keep the details of the stringing job to himself. But Mike Fishbach, an American player from Long Island struggling to get a foothold on tour, took a good look and decided he could recreate the effect himself. 30 hours of work later, he had his own spaghetti racket. Fishbach deployed it at the 1977 US Open. He made it through qualifying, then beat Billy Martin and Stan Smith.

The racket was such a sensation that it threatened to outshine the more conventional tennis elsewhere on the grounds. It didn’t take a traditionalist to object to the radically different effects that the double-strung weapon made possible. John Feaver, a Brit who earned more than a few clubhouse back-slaps by defeating Fishbach in the third round, described what he was up against:

You don’t know what’s going on with the bloody thing. You can’t hear the ball come off the racquet. It looks like an egg in flight, and you can’t pick it up until it’s halfway on you. When it bounces, it can jump a yard this way or that way, and up or down.

* * *

Everybody hated the new racket. But everyone also noticed that it worked. A few weeks after the Open, Năstase went to Paris, where he found himself bounced in the first round of the Coupe Porée by the unheralded Georges Goven. Goven’s racket was spaghetti-strung.

The Romanian didn’t approve, saying, “In future I shall refuse to play.” Patrice Dominguez was another early loser in Paris, and he led the French Union of Professional Tennis Players in seeking an immediate ban.

Christophe Roger-Vasselin made the finals of the Coupe Porée with a double-strung racket. The only man who could stop him was Vilas.

By the next week in Aix en Provence, Năstase had decided that he might as well join the crowd. The number of spaghetti stringing jobs kept increasing. Vilas faced one in the semi-finals, needing five strenuous sets to get past Eric Deblicker, a Frenchman even more anonymous than Goven. That put him in the final against Ilie.

Năstase wasn’t as good on clay as the Argentine–at that point, no one was–but he wasn’t far off. Combine Ilie’s shotmaking with the hyper-powered strings, and Vilas had no chance at all. Năstase won the first two sets, 6-1, 7-5, and Guillermo refused to continue.

Gene Mayer, a young American on tour, saw the match:

Năstase with his top spin off the spaghetti racket is impossible to play against unless you have the racket yourself. Guillermo worked his tail off. I’ve never seen him try harder. Those two sets were like seven. It’s a miracle–a monument to his strength–that he got those five games in the second set. Only he could get five. As far as the players are concerned that wasn’t a loss. Vilas’ clay-court streak was still alive.

A month later, the whole thing was moot, a wrong turn on the road to better equipment technology. The ITF placed a temporary ban on the stringing technique–made permanent the following year–and the USTA forbade it shortly thereafter. Fishbach picked up a few more wins, but Willie was untroubled by spaghetti rackets the rest of the season.

There is, however, a tantalizing postscript. Vilas–already the best, or second-best clay-court player in the world–couldn’t help but try out the double-strung racket himself. “[I]n his training matches,” said coach Ion Țiriac, “Guillermo simply is unbeatable!”

* * *

I went down the spaghetti-racket rabbit hole partly because I couldn’t resist, but partly to demonstrate just how far rivals had to go to challenge Vilas on clay. He was that good.

He arrived on the North American scene in 1974, a clay-court savant with a backhand that, as journalist Joe Jares described it, “lands in his opponent’s court at a zillion RPMs and scoots for cover like a terrified jackrabbit.” He mixed that up with a slice, and he was willing and able to run all day. In his breakout season as a 22-year-old, he picked up seven titles.

If anything was missing, it was the single-minded focus that would come to define his rival, Borg. Vilas styled himself a poet, even self-publishing a book. (It sold out two print runs. Reviews were, let us say, mixed.) He enjoyed his newfound celebrity and sampled the dating field of international starlets.

The Argentine also seemed to lack the vaunted killer instinct. Țiriac said, “This guy not capable in life to kill a fly.”

When Vilas teamed up with Țiriac–the Brașov Bulldozer who had led Năstase to superstardom and inspired every sports journalist on earth to learn the word “glowering”–he let the coach take over everything. Țiriac handled scheduling, endorsements, exhibitions, and more. If it were possible to outsource a killer instinct to one’s coach, Willie would’ve done it. The combination would’ve created the greatest tennis player of his era.

What Țiriac could do was ensure that his charge was the fittest man on tour. Fellow players would collapse halfway through Țiriac-Vilas practice sessions. The Romanian coach worked out a strategy for every opponent, then drilled it until it could be drilled no more.

In the 1977 US Open final, Vilas exposed a Connors weakness by constantly chipping to Jimbo’s forehand. “You like that shot?” Vilas asked reporters after match. “I practice that one nine hours or something [in the] last few days.”

* * *

1978 opened with the belated culmination of the 1977 season. The Masters event at Madison Square Garden was newly sponsored by Colgate, and the company shelled out enough cash to ensure that the big three–Borg, Connors, and Vilas–all showed up. The number one ranking–in hearts and minds, anyway, if not on the ATP computer–was at stake.

The round robin event settled nothing. Vilas beat Connors, Connors beat Borg, and Borg beat Vilas.

The Argentine still had a case for number one. But he relaxed and let Țiriac schedule a slew of big money exhibitions while Connors and Borg tightened their grip on the circuit. He dropped the Roland Garros final to the Swede in a match nearly as routine as his defeat of Gottfried the year before. At the US Open–now, alas, played on hard courts–he crashed out in the fourth round.

Peaking at the same time as Björn Borg, it turned out, was not a good idea.

Between 1976 and 1980, Vilas lost eleven straight meetings with the Swede. Willie remained a thorn in the side of everyone else on clay courts, especially the United States Davis Cup team when they were forced to play away ties in Buenos Aires. Vilas even developed a workable game for grass courts, picking up the 1978 and 1979 Australian Open titles against middling fields. But he never again threatened to become number one.

In the end, Vilas’s reputation as an all-time great rests on that exceptional 1977 season and his ability to rise above the already stratospheric levels of Connors and Borg. His time at the top was short, at least compared to the reigns of his two prime rivals. But he deserves to be recognized for achieving the number one ranking, even if the accolade comes nearly a half-century too late.