In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

John Newcombe [AUS]Born: 23 May 1944

Career: 1960-81

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1967)

Peak Elo rating: 2,209 (1st place, 1974)

Major singles titles: 7

Total singles titles: 76

* * *

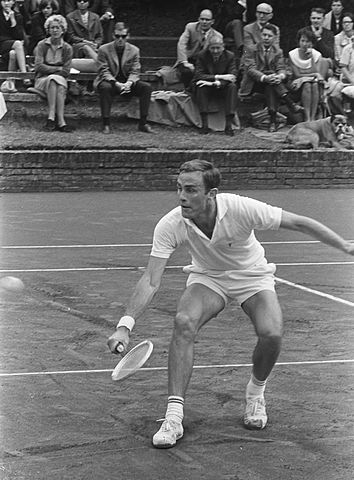

John Newcombe was the last Wimbledon champion before Open tennis transformed the game in 1968. For a young man of 23, he was quite experienced, making his seventh trip to the All-England Club. Harry Hopman had spotted his talent early on, letting him tag along on the Aussie Davis Cup squad’s circuit around the world when he was only 17.

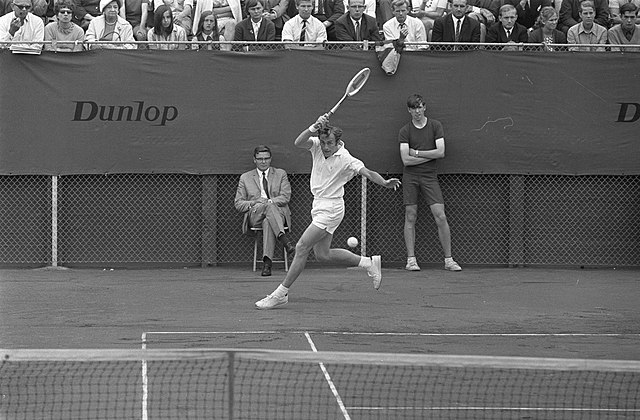

Newk was the king of the amateur tennis world in 1967. In addition to Wimbledon, he won the US Nationals at Forest Hills, led his nation to its fourth-straight Davis Cup championship, and picked up another ten titles besides. Out of 128 singles matches, he won 111. He had a “job” working for Slazenger, and it was only a matter of time before he’d sign on the dotted line and start collecting the big bucks in pro tennis.

By the time he dispatched Clark Graebner in the Forest Hills final, he and doubles partner Tony Roche had already come to an agreement with David Dixon, the promoter who, with billionaire Lamar Hunt, was putting together what would become the World Championship Tennis (WCT) tour. Newcombe and Roche were the anchors of what would become the “Handsome Eight.” They would play most of the year on the WCT circuit, and thanks to the revolution in tennis, they would be able to enter the majors, as well.

The bad news: Everybody else could sign up for the majors, too.

Fred Stolle turned up at Forest Hills in 1967 as a spectator. The defending champion, he was ineligible to play after joining the professionals. He joked he was there “to see how they pay the amateurs this year–under the table or over it.”

Before switching sides, Stolle had beaten Newk in 13 of 22 career meetings. Newcombe asked him, “[I]f I wanted to play the pros, what would I have to improve? My backhand and my second serve, would you say?” Stolle suggested the difference was more tactical, “which shots to try for winners off of.”

What strikes me about the exchange isn’t anything about Newk’s game, it’s that the superiority of the pros was taken as absolute truth. Newcombe lost only four games in the Wimbledon final that year, yet he recognized he was essentially playing in the minor leagues.

1968 would prove him right. Graebner and Arthur Ashe would stop him from reaching the semi-final at either Wimbledon or Forest Hills, and he’d lose 37 matches, including decisions to veterans Rod Laver and Ken Rosewall–men who the amateur-professional divide had long shielded him from. He lost five in a row in early February, another four straight a couple weeks later. He dropped six decisions that year to Dennis Ralston alone.

A lesser man would’ve accepted his new second-tier status in the game. The 24-year-old Newcombe, however, got back to work.

* * *

Here is the difference between the amateur game and Open men’s tennis, in one table. I’ve listed Newcombe’s match winning percentage, along with his age at Wimbledon, for each year from 1966 to 1974:

Year Age Win% 1966 22 78% 1967 23 87% 1968 24 65% 1969 25 70% 1970 26 74% 1971 27 77% 1972 28 78% 1973 29 73% 1974 30 87%

All of these are good seasons, don’t get me wrong. Even 1968 isn’t as much an outlier as the table makes it appear. The first WCT circuit included several round robins, especially at the beginning when Newk was adjusting to his new life as a touring pro. My Elo ratings, which take into account strength of opposition, rate Newcombe as the fourth best player at the end of the season, behind only Laver, Rosewall, and Ashe.

Still, the ’68 and ’69 campaigns were a bit of a letdown for a player who was nearly untouchable in his last amateur season.

1969 was marked by one near-miss after another. He beat Roche in a five-setter for the Italian title, then lost another five-setter to Tom Okker at the French. He upset Laver at Queen’s Club in the semi-final, then lost a heart-breaker of a two-setter to Stolle in the final, 6-3, 22-20. Laver beat him in four in the Wimbledon final, then dispatched him again in Boston two weeks later. At the US Open, he got past Stolle, 13-11 in the fifth, then lost to Roche–yet another five-set struggle–in the semis.

Newk and Roche were not just doubles partners, they were close friends. None of that mattered on the singles court. “Some of the hardest matches I’ve ever played, real blood and thunder five-setters, were against Tony,” Newcombe said.

The Elo formula credits him with another fourth-place finish, now behind Laver, Roche, and Okker. In the year of Laver’s Grand Slam, however, the glory that Newk had reached just two years before must have felt very far away.

* * *

With so much money on the line, there was now more to tennis success than simply piling up tournament victories. As Newcombe matured, he added to his appeal on the both the tangible and less-tangible sides of the ledger.

In 1967, the 23-year-old from Sydney was just another serve-and-volleyer, albeit the best of the amateur pack. He could boast a strong serve–both first and second–and a powerful forehand. His backhand was functional, and anyway, the rest of his game was strong enough to hide it. His game was even better suited to doubles than to singles; he won six doubles majors as an amateur (five of them with Roche) and eleven more in the Open era.

Many fans, understandably, saw Newcombe as little more than the latest Aussie. The parade of stars from Down Under had been winning most of the majors for 15 years, many of them with the same combination of fitness and big-game tactics that Newk offered. Frank Deford saw the potential for more:

Even now, Newcombe plays the net with his own special daring—on top of it, challenging, like a third baseman moving in close, defying a potential bunter to hit away. And his on-court peculiarities–shirttail out, tousled towhead, a large inurbane grunt that he dispenses with each serve–can become crowd-pleasing characteristics. The considerable charm of the private Newcombe is unlikely to remain hidden within the public one.

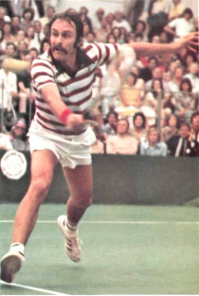

The Sydneysider would never become Ilie Năstase, but in time, he would cash in on his own brand of crowd-pleasing charm. First, he doubled down on the aspects of his game that made him an amateur champion.

It’s uncanny how many of Newk’s skills were described as the very best on the circuit. Jack Kramer said he had never seen a better second serve. In 1970, Sports Illustrated described his forehand as “perhaps the strongest in tennis.” Deford credited him with “a scrambler’s lob the equal of anybody’s,” and he emphasized that Newcombe’s head and heart were even better than his stroke equipment.

As for the backhand… In the first game of the 1968 Wimbledon doubles final, he smacked the hardest backhand winner of his life. Fred Stolle, on the other side of the net, wasn’t worried. “We don’t have to worry about that shot any more–now that you’ve hit your one for the year!”

* * *

In 1970, Newcombe returned to the Wimbledon winner’s circle. His opponent was the 35-year-old Ken Rosewall, part of the 1953 Davis Cup-winning team that inspired the nine-year-old John to pursue tennis in the first place.

The press box was pulling for the veteran, a sentimental favorite who would never win Wimbledon despite reaching four finals. Rosewall gave them hope, pulling out the fourth set after Newcombe took a two-to-one lead, but he couldn’t withstand Newk’s attack. The younger man won the fifth set, 6-1.

By then, Newcombe had earned a reputation as a man to fear in long matches. In the quarter-finals of the same tournament, he outlasted Roy Emerson after losing the second and third sets. It was a momentous struggle to finish the job, 11-9 in the fifth. An early proponent of advance scouting, Newk would keep an opponent guessing until the very end. He liked to keep a tactic or two in his back pocket, ready to spring something new if he ended up in a deciding set.

Most of all, he backed himself to the hilt when matches got tight. One journalist noted in 1970, “It is said in tennis that Newcombe is so tough when he is behind that you have to shoot him to win.” He could lose interest when he was winning, but never when there was ground to make up. “I’m at my best in a five-set match, especially if I get behind. My adrenaline starts pumping.”

One fellow player said in 1975 that Newcombe was “the cockiest guy around, cockier than [Jimmy] Connors.” Hard as that is to believe, his self-belief could reach staggering levels. For Rod Laver and Larry Writer’s 2019 book, The Golden Era, he told the authors that he won “80-90 per cent” of his five-setters. That is a truly impressive rate. Alas, it was not his. I count 86 five-set matches in his singles career, of which he won 52–a respectable but much more human win rate of 60%.

* * *

Fans could be forgiven for believing Newk’s hyperbole. He almost never lost a five-setter when the stakes were high. He won seven of nine Open era finals that went the distance, and between 1966 and the end of his career, he won 17 of 23 five-setters at majors.

One of those was his signature match, even more memorable than the Wimbledon final against Rosewall. In 1971, he waltzed past the veteran, 6-1, 6-1, 6-3 in the semi-final. His reward was a final against Stan Smith. Newk won more than half of his career meetings with the American, but it was never easy:

Stan tries to overpower you mentally. A certain amount of that is the way he plays–the steamroller, smothering you at the net. But I can deal with that. What is more tiring is his air–that smug confidence. You must concentrate all the time or you’ll give up. Nobody wears me out like Smith does, but it’s not from the tennis, it’s mental fatigue.

Newcombe lost the second and third sets. He won the fourth, but found himself one point away from dropping to 4-1 in the decider. From there, wrote Rex Bellamy, “Newcombe fought back with the fury of a wounded but indomitable lion who knew he had to kill or be killed.” In the end, mental fatigue got to the American, not the Australian. Smith double-faulted on the final point to give Newcombe the match.

The two men faced off again in the 1973 Davis Cup Challenge Round in Cleveland. The United States had held the Cup since 1968, but many observers felt that it hardly counted. Contract pros were forbidden from the competition, so a veritable wing of the Hall of Fame–Laver, Rosewall, Emerson, Stolle, Newcombe, Roche, and more–was kept off the Australian side. The rules finally caught up with the times in 1973, and a “Dad’s Army” of veteran Aussies assembled for the campaign.

Newcombe-Smith was the first match of the tie, and it didn’t disappoint. Newk served big, and even his backhand chalked up winners. In a little over three hours, the Australian scored another five-set victory. The next day, he paired with Rod Laver to finish the job. Smith and Erik van Dillen didn’t stand a chance: The Aussies won the doubles with the loss of only seven games.

* * *

The 1973 Davis Cup represented the end of an era. Laver and Rosewall were getting old. Harry Hopman, the man who had guided generations of Australian stars, had moved on to work at an academy in New York. The increasingly global spread of the game meant that while you could still find Aussies in the draw of just about every tournament, it was no longer a lock that the final would involve two of them.

But John Newcombe still had something to prove.

By his mid-twenties, Newk sought a balance between tennis and life. A few grueling seasons–128 matches in 1967, the first WCT tour in 1968–drove him to establish a comfortable home where he could recover from the rigors of the road. He bought a ranch in New Braunfels, Texas, built it up to become a tennis mecca, and rarely missed a chance to spend extended stretches there.

With national pride on the line, he refocused for the 1973 Davis Cup. Before the triumph in Cleveland, he won his fifth singles major, beating Jan Kodeš in another high-profile five-setter. Now 29 years old, his self-confidence and approach to the game had hardly changed. “I knew that if I kept hitting the same shots at him,” he told Sports Illustrated, “he could keep it up for 50 minutes or an hour, but not for an hour and a half.”

The Cup in the bag, his target was to become number one on the new ATP computer ranking. He got there, in part, by playing more tennis than he had ever played before. By June, he had won six titles, and despite never crossing paths with the reigning top dog, Ilie Năstase, he gained the number one position in June.

Alas, he lost to the ageless Rosewall in the Wimbledon quarter-finals, and the tournament’s winner, Jimmy Connors, became king of the ATP computer a few weeks later. Newcombe couldn’t strike back, since he was busy playing the first season of World Team Tennis. At the US Open, he lost to Rosewall again.

As Connors solidified his status at the top of the game–he would hold the top ranking for more than three years–the come-from-behind champion still had one more triumph in his racket bag.

Newcombe arrived at the 1975 Australian Open in mediocre form. He still ranked second to Connors, but in two months, he had lost to the likes of Phil Dent, Geoff Masters, and Ismail El Shafei. He hardly looked better in the second round when he needed five sets to get past Rolf Gehring, a German ranked outside of the top 200 in the world.

It would be an exaggeration to say he quickly played his way into form. He just squeaked past Masters in the quarters, losing a third-set tiebreak before sneaking out of a 10-8 fifth set. His opponent in the semi-finals was Tony Roche. As they had so many times before, the long-time partners and friends refused to give an inch. Newcombe advanced by nearly as close a margin as he had in the round before, 9-7 in the decider.

Connors awaited in the final. Finally, “six months of verbal warfare” would be settled on the court. Whatever the computer spat out, Newk still considered himself the man to beat. He had defeated Connors in their two 1974 meetings. In Melbourne, he made it three. Jimbo’s fearsome return of serve kept Newcombe pinned to the baseline, but the veteran still managed to come through in four, 7-5, 3-6, 6-4, 7-6.

* * *

The 1975 Australian title gave Newcombe seven major championships in singles to go with 16 doubles slams. He’d add a 17th in Melbourne the following year.

But his days of beating Connors were over. They faced off in a exhibition-style challenge match in Las Vegas a few months later. This time, Jimbo won in four, and he’d never lose to the Australian again.

Newcombe’s late-career resurgence, however, made him a rich man. He walked away with about $300,000 (about $1.6 million in today’s dollars) from the Connors match alone. By that time, he was endorsing rackets, resorts, watches, luggage, and shoes. His Texas tennis ranch, offering clinics to socialites, had spawned franchises.

While he would never return to number one, he remained capable of testing the best players on the planet for years. In 1981, he entered the US Open with Fred Stolle, another man who had been winning majors since the days of amateur tennis. They made a surprise run to the semi-finals, falling only after they pushed John McEnroe and Peter Fleming to a fifth set.

McEnroe was the kind of doubles player he respected–a singles standout whose skills applied just as well to the doubles court. Long after his retirement, Newcombe told Rod Laver, “[Bob Bryan and Mike Bryan] play a nice game of doubles and best of luck to them. In our day they’d have been lucky to make the quarters. Look at the teams they’ve beaten in the grand slams, doubles specialists who wouldn’t be among the top 100 singles players.”

I suspect the Bryans would’ve done just fine in the 1960s, ’70s, or any other era. But Newk is entitled to his opinion. If anyone knows what it takes to win tennis matches regardless of context–singles, doubles, amateur, professional, exhibition, knockout, round robin, Davis Cup, Team Tennis, you name it–it is John Newcombe.