In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

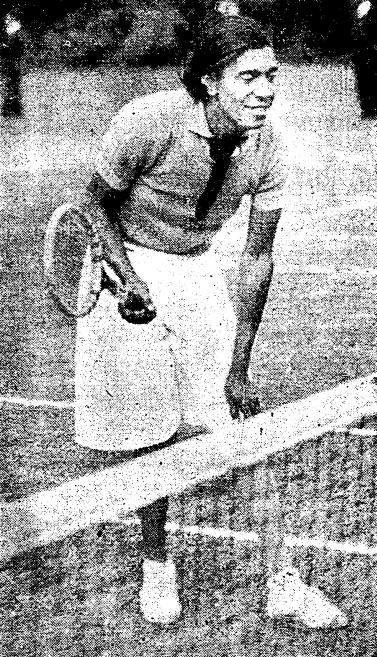

Ora Washington [USA]Born: 1898 or 1899

Died: 21 December 1971

Career: 1924-47

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (ATA national ranking)

Major singles titles: 0 (in 0 attempts)

Total singles titles: At least 36

* * *

For a century or more, the tennis world has been remarkably interconnected. The preeminence of Wimbledon, Forest Hills, and the Davis Cup meant that the strongest competitors of the amateur era regularly faced off against each other. The amateur-professional divide split the field for a few decades, but even then, players earned their spots on a pro tour mainly by winning championships on the amateur circuit.

We measure the all-time greats by their performances against each other, on the sport’s biggest stages. So how do we rate a superstar who wasn’t allowed to compete against the best players of her era, or even to set foot in the most famous venues?

Before 1950, tennis in the United States was racially segregated. Black players were not welcome at the clubs where the most important tournaments were held, and they were explicitly barred from competing in most sanctioned events. Apart from a handful of exhibition matches, there was no meaningful interracial competition in tennis until Althea Gibson made her first appearance at the US National Championships.

Tennis isn’t alone in its shameful, racist past. Major League Baseball, for example, was desegregated only three years earlier. But as other sports have celebrated the exploits of their pre-integration Black stars, tennis has largely ignored its own. The Baseball Hall of Fame has inducted dozens of Negro League players. By contrast, the honor roll at the International Tennis Hall of Fame suggests that the Black game began with Althea and her mentor, Dr. Robert Walter Johnson.

Black tennis thrived before Gibson. There were Black champions even before Althea was born. When Arthur Ashe finished the magisterial volumes of A Hard Road to Glory, he concluded that one of those early greats “may have been the best female athlete ever.”

That was Ora Washington.

* * *

Washington is best remembered today as a basketball player. She toiled in segregated obscurity in that sport as well, but basketball–like baseball–has taken strides to recognize its Black pioneers. Ora was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2018. The Women’s Basketball Hall had already honored her in 2009.

She led the champion Philadelphia Tribune team throughout the 1930s. Despite standing a modest five-feet-seven-inches tall, Ora played center. She often led her squad in scoring, and she always intimidated her counterparts. One opponent remembered, “I never saw her when she hit me, but she did it so quick it would knock the breath out of me.”

Her page at the Basketball Hall of Fame website doesn’t mention her tennis exploits. The Women’s Hall page allows that she was “[a]lso a star tennis player.”

This is true. Just like a contributing editor at the Hollywood Reporter, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, also played a bit of basketball.

Tennis was Ora’s first serious competitive pursuit, even if it was hardly her start in sports. She was born in Virginia to a large family, one in which outdoor games such as croquet were a constant feature. When the Washington clan hit hard times, an aunt moved to Philadelphia. Ora, also in search of work, followed. On her days off from cleaning houses, she hung out at the Germantown YWCA, one of the few gathering places for Black women that maintained tennis courts.

She picked up a racket in 1924, and she won her first titles in Wilmington, Delaware later that summer. Just a year later, she put the Black tennis world on notice. She upset Chicagoan Isadore Channels, the 1924 national champion, and she won the doubles title at the American Tennis Association (ATA) national tournament. In 1929, she would claim her first of eight ATA singles championships. There was no higher accolade available to Black tennis players at the time, and before Althea Gibson came along, no one achieved it as often as she did. No one came close.

Ashe didn’t exaggerate: Washington was in a class by herself. Whether you considered her a hoopster who dabbled in tennis or a racket wielder who filled her spare time with basketball, she was royalty. The papers called her “Queen Ora.”

* * *

We’re still at work on a full accounting of Washington’s on-court exploits. Tennis Abstract credits her with 35 singles titles, spanning 104 match wins against only 11 losses. I found a 36th title last week in the course of researching this essay, and when we consider doubles victories, she probably retired with well over 100 championships to her name.

The match-by-match victory tally is woefully incomplete. While some tournaments had small draws, requiring only two or three singles wins for a title, ATA national events often went through six rounds. Most Black newspapers were weeklies, so they would report a few notable results from the first day’s play, then follow up with a recap of the finals. White publications generally ignored the events entirely. For many of Washington’s triumphs, we don’t know the identity of more than one or two of her opponents or the scores by which she cast them aside.

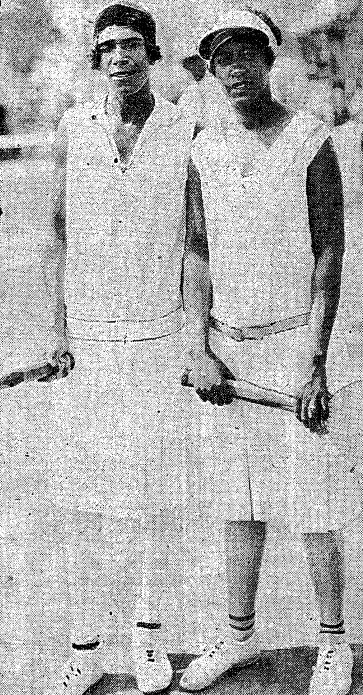

Just as the 104 known wins understate her dominance, her 11 defeats overstate her vulnerability. Seven of those rare losses came at the hands of Lula Ballard, a fellow Philadelphian and frequent doubles partner who picked up a national championship before the reign of Queen Ora began. Ballard also doubled as a basketball star, and she swung a racket more gracefully than Washington did. Ora maintained a slim edge in their career encounters, winning 10 of 17, many of which went to three sets.

Washington devoted more time to tennis than her rival did, and no one could touch her in her steady battering of the rest of the field. Against everyone else, Ora won 94 of 98 known matches. The New York Age compared her to the boxer Joe Louis, another Black star who won with “deadening regularity.” Beginning in 1928, Washington went undefeated for nearly eight years.

The uncertainty about Ora’s stats extends to just about every aspect of her life. Her home county in Virginia didn’t keep records, so we don’t have her exact birthdate. All we can say is that she was probably born in 1898 or 1899. We know roughly when she started playing tennis, but we can’t be confident of the oft-repeated story that she picked up the sport to get over the death of a sister.

Washington frequently appeared in the headlines during her sporting career, but she drew little attention in retirement. New stars grabbed the spotlight, and integration shifted the focus away from organizations like the ATA. Ora did little to spread her own story. Her obscurity was so complete that when the Black Athletes Hall of Fame inducted her in 1976, no one knew why she didn’t show up. She had died five years earlier.

The resuscitation of her basketball record has given us a bit of a 21st-century Washington revival. Deserved as it is, our knowledge of her life and career hasn’t kept pace. Stories about her have turned into a game of historical telephone. The Basketball Hall of Fame initially honored her as “Ora Mae Washington.” Just one problem: That wasn’t her name. No one knows exactly where the “Mae” came from, but it didn’t come from Ora. Her middle name was Belle.

* * *

The most frequently repeated–and gradually twisted–story about Ora concerns her desire to take on the greatest player of her era, Helen Wills Moody.

Ora knew she was the best player around, and she surely wondered how she would stack up against even stronger competition. In the early 1930s, Helen Wills Moody was the strongest of all. She won 14 majors–six of them at Wimbledon–between 1927 and 1933.

By the end of Washington’s life, reporters would write that her dream had been to test herself against Wills Moody. No match ever happened–or was even seriously discussed. The non-match has somehow developed a mythology. Wikipedia makes a poorly-sourced claim that “Moody refused to schedule a match,” and many journalists have repeated it, sometimes insinuating that Helen wouldn’t play because she was either too racist, too insecure, or both.

I don’t doubt that Ora wanted the challenge. It would’ve been a huge opportunity for her, and it could’ve accelerated the path to integrated tennis. In the 1940s, Don Budge and Alice Marble played exhibitions with Black players and Marble–along with Sarah Palfrey Cooke and others–pressured the establishment to open its doors to Althea Gibson.

But there’s no evidence that any kind of overture to Wills Moody was made at the time. When a reporter asked her about the non-match in 1976, Helen didn’t remember anything about it, or about Ora. Wills Moody played a very limited schedule, and even a prospective title defense at Forest Hills or Wimbledon didn’t always convince her to leave her home in California. The whole idea of a Wills-Washington showdown was always far-fetched, even if we assume the best of intentions on Wills Moody’s part.

* * *

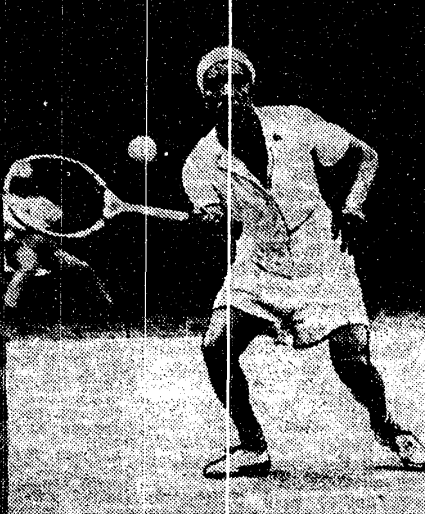

From our vantage point nearly 100 years later, it’s impossible to know how Ora would’ve fared against the toughest competition of her day. We have mixed reports of her serve, rave reviews of her overhead, and awed tales of her footspeed. She choked up on the racket, and her groundstrokes–particularly a backhand slice–were old-fashioned. Her only chance against Wills Moody probably would’ve been to chop her into submission, the strategy that worked for Elizabeth Ryan.

Ora’s success relied in part on the same intimidating reputation that preceded her on the basketball court. The Chicago Defender wrote in 1931, “[H]er superiority is so evident that her competitors are frequently beaten before the first ball crosses the net.” It’s unlikely that a top-ranked white star would’ve succumbed so quickly.

Baseball researchers are able to approximate the level of play in the pre-integration Negro Leagues. Even with the official color line in place, there was a fair amount of interracial competition. All-star teams of Negro League and Major League players barnstormed against each other in the offseason. We can also look at the records of players such as Jackie Robinson, who spent one year on one side of the divide before shifting to the other.

Tennis has almost nothing of the sort. Black players occasionally entered local public parks tournaments, with some success. Frances Gittens*, a New York-based ATA star who lost her 15 matches against Ora, won at least one parks tournament in Brooklyn against predominantly white competition. Flora Lomax, a national champion in the years following Washington’s retirement from singles competition, played several interracial tournaments in Detroit, often beating the field. A Californian named Juliette Harris held her own in Los Angeles public parks competition, once taking Gracyn Wheeler–a future Forest Hills quarter-finalist–to a third set.**

* Before Frances married fellow player Mr. Gittens, she was, believe it or not, Frances Forehand.

** In 1930, Harris found herself across the net from Dr. Esther Bartosh, around the time that Bartosh began coaching the young Bobby Riggs.

Those three examples aren’t the full extent of interracial women’s competition in the pre-Althea years, but they are frustratingly close. Each one implies that there was plenty of talent blocked by the sport’s color barrier, but the sum of the evidence is not nearly enough to draw stronger conclusions.

* * *

For Black journalists in the 1950s, the most compelling hypothetical was historical, not racial. Who was better: Ora Washington or Althea Gibson? In 1953, Sam Lacy of the Baltimore Afro-American imagined a clash between the two women at their peaks, composing a blow-by-blow report for the fictional match. Lacy gave Althea a slight edge, with a final score of 3-6, 6-3, 8-6.

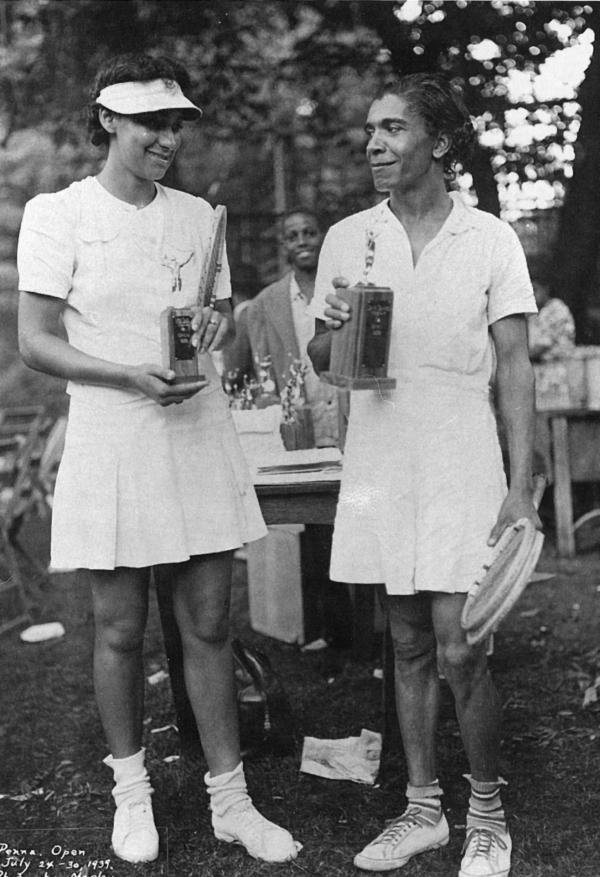

Left to right: Stewart, Washington, Dr. Robert Walter Johnson, and Althea Gibson

Philadelphia Tribune reporter Malcolm Poindexter offered a more measured comparison in 1956, the year Gibson won her first major title. He made it clear that Ora had her supporters, and that “Miss Washington [could] have given Helen Jacobs or the other great women of her day a real tussle.” But one local connoisseur, Al Bishop, sided with Althea:

[Ora’s] court game was old style…. She had the tactics, and was dynamic to watch. But she didn’t have the stroke. Her overhead game was terrific, but even that wouldn’t have helped too much…. Ora played a different style game entirely.

That brings us back to where we started. We can’t compare Washington to Jacobs or Wills Moody because they never faced off, and they had no opponents in common. We can’t really compare Ora to Althea–even though they did sometimes share a doubles court–because they belong to different eras. Washington was never part of the globally interconnected tennis world. For all that an analytical approach can tell us, Ora might as well have been the champion of Lapland.

The truth of the matter is, Washington probably wasn’t as strong as the all-time greats people want to stack her up against.

The most damaging aspect of segregation wasn’t the exclusion of Black players from top-level competition, it was the complete lack of opportunities for talented youngsters to develop into future champions. Ora probably never saw a tennis court until she was in her early twenties. She never had a coach. She had so little financial support that she continued cleaning houses even while she was a two-sport superstar.

She overcame all that, and she still beat all comers–many of them upper-middle-class young women who would never work a menial job in their lives. She overcame all that, and she still played such impressive tennis that old-timers would put her on par with the Wimbledon-winning Althea Gibson. No better player could possibly have emerged from the milieu of 1920s Black Philadelphia.

It was just as unlikely that a woman with Ora’s background would become one of the great basketball players of all time. Yet 100 years later, she has a plaque at that sport’s Hall of Fame.

It’s well past time that she receives the same recognition for her tennis.