In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Nancy Richey [USA]Born: 24 August 1942

Career: 1959-78

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 2 (1969)

Peak Elo rating: 2,345 (2nd place, 1965)

Major singles titles: 2

Total singles titles: 72

At the end of 1965, the leaders of the United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA) voted to finalize their annual rankings. The responsible committee had already generated a list. Usually, all that was left was a rubber stamp.

The ranking committee gave the top women’s place for the 1965 season to the 22-year-old, recently-married Billie Jean King. She had a good case: six titles, including a sweep of the summer grass-court circuit leading up to Forest Hills. She had reached the semi-finals at Wimbledon and the final at the US National Championships, where she lost to Margaret Smith (now Margaret Court).

The representative from Texas wasn’t so sure. He stood up to propose dropping King to number two, behind the Lone Star State’s own Nancy Richey. Richey, 15 months older than King at 23 years of age, also had the makings of a sterling national number one. Her 1965 haul included seven titles on four different surfaces. Three of them required final-round victories over Smith. Richey and King hadn’t played each other in 1965, but in four encounters the year before, Nancy won three.

No one seconded the proposal to move Richey to number one. But a compromise was struck: Billie Jean and Nancy would be co-ranked number one.

If there hadn’t been a rivalry between the two women before, there certainly was now.

* * *

Richey was the perfect foil for Billie Jean and her aggressive serve-and-volley game. King excelled on grass, untroubled by bad bounces because her high-energy style rarely allowed the ball to touch the ground.

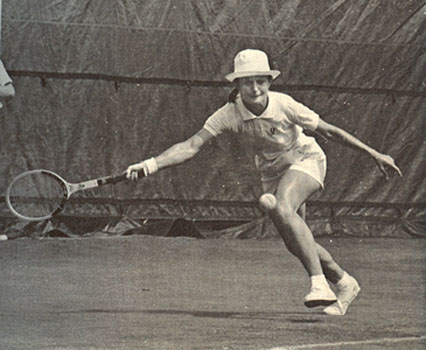

Nancy was a clay-courter through-and-through. Dirt was the most common court surface back home in Texas, and she developed the game to match. While she wasn’t particularly fast, she was a grinder of the first order. In 1960, the New York Times pegged the 17-year-old as “a girl who will run after a ball even into the next court.”

She ran, but she rarely ran forward. While her volleys were serviceable, her mobility at net was subpar. Usually it didn’t matter. In 1964, World Tennis described her forehand and backhand as “the hardest groundstrokes in the game.” She was dubbed the “Two-Shot Texan” and drew comparisons with another great baseliner, Maureen Connolly.

Richey’s persistence wasn’t limited to those times when an opponent stood across the net. She quickly developed a reputation for a practice regimen–and single-mindedness–that would kill most of her peers. The first time she played Julie Heldman, in Puerto Rico in 1962, she won 6-0, 6-0. Then she headed back out to the courts for several hours of practice.

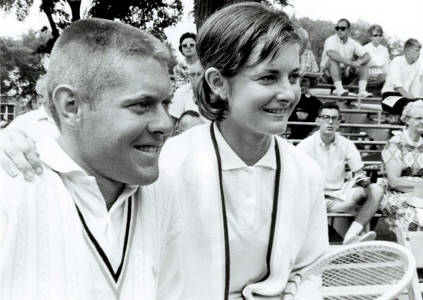

She came by her doggedness honestly. Her father, George Richey, showed promise as a baseball pitcher before injuring his throwing elbow at age 14. Tennis was the only one-armed sport he knew of, so that’s what he picked up. He didn’t have the freedom to pursue the amateur game, but as a teaching pro, he was good enough to crack the top ten in the world professional rankings. Not bad for a righty playing left-handed. He even scored a couple of wins against another coach with good tennis genes, a Floridian named Jimmy Evert.

George didn’t force his kids to play tennis. But when they showed interest, he demanded that they give it their all. That suited Nancy fine. Her brother Cliff, four years younger, became even more single-minded. In an era when most events were joint tournaments for men and women, the Richey family spent much of the year traveling together. They lived and breathed tennis.

And they practiced.

* * *

For years, the King-Richey rivalry sat on the backburner. Billie Jean played in California and on the Eastern grass-court circuit. Nancy dominated the National Clay Court Championships in the Midwest, and she spent more time in Europe.

They might have met at the 1966 U.S. Indoors in Boston, where Richey would have been the defending champion. But on a tour of Australia, she tore the cartilage in her left knee. It forced her to default her first major singles final, at the Australian Championships to Smith, and it knocked her out of action until April. King won the indoor event easily.

Nancy made a trip into King territory, to the National Hard Court Championships in La Jolla. But she lost in the quarters, two rounds before she would’ve met her rival. Both women played Wimbledon, where King won her maiden major singles title. Richey won the doubles with Maria Bueno, but lost in the singles quarter-final. At Forest Hills, Nancy made the final–her third runner-up finish at a major that year–while Billie Jean lost early.

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

Deprived of an on-court outlet, the ladies were reduced to a war of words. King accused Richey of skipping the Forest Hills warmups on grass in order to avoid playing her. Nancy said the same about Billie Jean’s decision not to enter the U.S. Clay Courts. Clark Graebner neatly summed up the state of play in 1966:

Women’s tennis is awful. I can’t stand it. But if those two play each other at Forest Hills, I’d walk from my house in Cleveland to New York to watch that match. They’ll be going at each other with sledgehammers.

* * *

The rivalry would have to wait until March of 1968 for any kind of resolution. Both women continued in stellar form. Richey went back to Australia in 1967, where she picked up her first major singles title. King defended her Wimbledon title, untroubled by Nancy, a fourth-round loser. Richey won her fifth straight title at the U.S. Clay Courts. Billie Jean showed up but failed to force a meeting when she suffered an uncharacteristic loss to Rosie Casals.

King and Richey were teammates for Wightman Cup in August. Both women swept their singles matches, but Richey wrenched her back in a tough three-setter with Virginia Wade. She would miss the rest of the season, forced to watch as Billie Jean added the Forest Hills crown to her ever-lengthening list of laurels.

Nancy’s injury couldn’t have come at a worse time. Promoter George MacCall was putting together a group of four women who would compete alongside his troupe of professional male players. His first choices were Billie Jean, Margaret Court, Bueno, and Richey. But he didn’t want to take his chances with the Texan’s back. Court and Bueno weren’t ready to take the plunge, so the opportunity went instead to King, Casals, Ann Jones, and Françoise Dürr.

As it turned out, Richey would’ve been fine. The pro circuit didn’t get underway until April of 1968, and Nancy returned to action at the beginning of March, winning her first tournament back.

Three weeks later, fans were finally treated to the long-awaited clash between the top American women. At the Garden Challenge in New York City, both women won their first two matches in straights. That set up a semi-final match, their first meeting in nearly four years.

Just about everything favored Billie Jean. She was on a tear, having won five consecutive titles, including the Australian Championships and the U.S. Indoors. The indoor wood surface worked to her advantage as well. Still, the woman who had just beaten Margaret Court twice in front of the Australian’s home crowds knew how much was at stake. “I was unbelievably tense,” King said. “I wanted to beat her so badly I could taste it.”

She almost did. King won the first set, 6-4, and she built a 5-1 lead in the second. Richey broke her and fought back to 5-3. In the ninth game, Billie Jean reached match point, and Nancy floated a weak lob to her backhand. It was a shot King had put away hundreds of times, but she took too long deciding to hit a smash, and she missed by a foot and a half. Her confidence shaken, she was broken again. Richey never let go, winning three more games for the second and another six for the third.

From match point down, Nancy won 12 games in a row. “I still wake up from nightmares thinking about that match,” Billie Jean said later that year. “It was my all time worst match.”

They met again two months later, at Roland Garros. In the semi-final, Richey won again, coming back from a one-set deficit to do so. She had now won six of seven career matches against her top countrywoman, and she came back in the final to beat another difficult rival, Ann Jones. Jones had defeated her easily in the 1966 final, but now, America’s top clay court player had taken the world’s preeminent clay court championship.

* * *

1968 was a confusing–if exciting–time to be a tennis player. The sport’s governing bodies had finally agreed to allow professionals to compete alongside amateurs. Players were required to identify as one or the other; some tournaments still didn’t admit pros. Certain competitors, like the MacCall quartet, were “contract” pros, and others–who would play for prize money and remain tied to their national federations–were known as “registered” professionals.

The compromise was serviceable, except for one thing. The USLTA didn’t initially permit its players to become “registered.” Anyone not signed as a contract pro, including stars such as Richey and Arthur Ashe, had no choice but to remain amateur.

Thus, when Richey won the first French Championships of the Open era, she was unable to claim the $1,000 first prize. Jones, the contract pro, got $600 for her runner-up finish, while Nancy settled for a voucher worth $400.

The same situation–minus the voucher–threatened at the upcoming US Open. Richey had long bristled against the status quo of tournament-player relations in the amateur era. Tournaments, she said, “treated the players like dirt and then raked in the money.” With no way to turn pro in the eyes of the USLTA, she demanded modest “expenses” of $900–essentially an appearance fee–to play her national tournament.

The USLTA called her bluff, and she sat out the Open. It was a shame for both player and tournament. Richey had been playing brilliant tennis all year, losing only three matches against 56 wins. Maybe Billie Jean would’ve gotten the better of her on grass courts. Or maybe eventual winner Virginia Wade, who had beaten her in Wightman Cup play, would’ve defeated her again. But we’ll never know, all for the paltry sum of $900.

Looking back, Richey wishes she had handled things differently. “I do regret that I did not play…. I cut off my nose to spite my face.” Even the USLTA implicitly admitted it had been wrong. That offseason, the organization finally instituted the registered player rule.

* * *

In 1969, Richey entered the US Open, beating King in the quarters and losing to Court in the final. It was her last major final, and while she would continue to play great tennis throughout the first half of the 1970s, the 1969 season represented the beginning of the end.

She lost to Billie Jean at the South African Championships in April, then pulled a calf muscle attempting to defend her French title. In July, she finally lost her six-year stranglehold on the U.S. Clay Court title. A far inferior player, Gail Chanfreau, beat her in the final with loopy forehands and backhand slices. The combination made it tough for Richey to establish a rhythm, and both King and Casals would adopt similar tactics against her.

Personal challenges also kept Richey from sustaining her high level of 1968. As Open tennis evolved, there were fewer and fewer joint events. Nancy could no longer spend so much time with her father and brother. Cliff had surreptitiously coached her to her Roland Garros title, but with increasing frequency, there was no one from her camp sitting on the sidelines.

Then at the end of 1970, she married Kenneth Gunter. She wasn’t as motivated to spend so much time on the road, and she didn’t remain as focused on tennis. As the relationship went sour, it became an even greater distraction. She watched as Billie Jean improved her game and racked up the acclaim. By early 1972, King finally evened up their head-to-head at nine matches apiece.

* * *

King was the better player of the 1970s, and just about any measure of tennis greatness gives her the nod over her early rival. But let’s go back to that 1965 co-ranking. Long into retirement, Nancy continued to believe she deserved the top spot to herself.

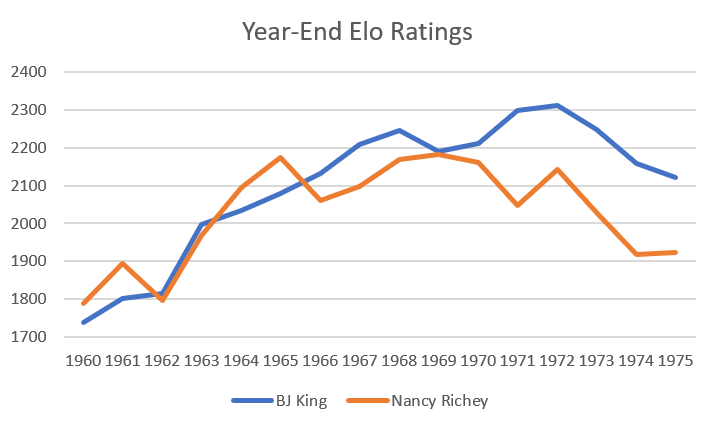

Here and King and Richey’s year-end Elo ratings from 1960 to 1975:

Nancy held a clear edge at the close of both 1964 and 1965. When the USLTA judged their performances as a tie, at the end of 1965, Richey had a substantial 93-point edge.

In the years that they didn’t play each other, King faced a tougher schedule, stayed healthy, and took back the advantage. But in 1969, Richey concluded her last great season with a defeat of her rival at the Howard Hughes Open in Las Vegas, and the two women finished in a dead heat.

Eight years later, they were still fighting it out. Billie Jean spent the 1976-77 offseason rehabbing her knee, and the 33-year-old returned at the $110,000 Family Circle Cup in March. For her first match back, she drew a qualifier–the 34-year-old Nancy Richey. On the familiar clay, Richey raced out to a 6-0 first set. But King clawed back to take a second-set tiebreak and win the match, 6-2 in the third.

Nancy would soldier on for another 18 months, winning the Southern Championships in Raleigh that June, and reaching the final of the U.S. Clay Courts in August. She claimed her last US Open match victories that year, when she played her way to a fourth-round meeting with Chris Evert. Evert beat her easily, 6-0, 6-3, just as she had handily dispatched King at Hilton Head. Richey had won her first five meetings with Chrissie, but she had long since passed on her crown as the leading American baseliner.

It had been nearly three decades since George Richey told his daughter that he would only coach her if she would give 150%. Nancy more than held up her end of the deal.