In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Tony Trabert [USA]Born: 16 August 1930

Died: 3 February 2021

Career: 1948-63

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1953)

Major singles titles: 5

Total singles titles: 56

* * *

It’s hard to overstate the extent to which California ruled American tennis in the amateur era. Westerners such as Maurice McLoughlin, Bill Johnston, May Sutton Bundy, and Hazel Hotchkiss Wightman were taking national titles even before World War I.

Philadelphian Bill Tilden kept the balance of power tilted eastward throughout the 1920s, but it was only temporary. Here is a list of the American men who won the US national title between 1930 and the end of the amateur era:

PLAYER HOME STATE John Doeg SoCal Ellsworth Vines SoCal Wilmer Allison Texas Don Budge NorCal Bobby Riggs SoCal Don McNeill Oklahoma Ted Schroeder SoCal Joe Hunt SoCal Frank Parker Wisconsin* Jack Kramer SoCal Richard González SoCal Art Larsen NorCal Tony Trabert Ohio Vic Seixas Pennsylvania

I’ve separated Southern and Northern California to emphasize just how much Los Angeles dominated the country’s tennis. 9 of these 14 players hailed from California, and one of the others–Frank Parker–spent some of his formative years in L.A.

If we count by titles, the gap is even more dramatic. Californians won 14 national championships to 7 for the rest of the country. It’s 16 to 5 if we class Parker with the West Coasters. Even that doesn’t tell the whole story. Most of the other best Americans of the era, such as Frank Kovacs, Budge Patty, and 1948 Wimbledon champ Bob Falkenburg, also hailed from California. A similar list for women would also be blanketed by Westerners, from Helen Wills to Billie Jean King.

The Golden State, and the City of Angels in particular, offered year-round tennis weather, plenty of courts, an ample supply of skilled coaches, frequent tournament play with age-based junior divisions, and local heroes made good.

Tony Trabert grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio. He had none of those things.

* * *

Well, okay, he had a few advantages. Cincinnati wasn’t as tennis-deprived as Chickasha, Oklahoma, the hometown of 1940 champ Don McNeill. Arch Trabert raised his sons to play any sport on offer, and there were playground courts down the block from Tony’s childhood home.

Arch wasn’t much help on the tennis court–his best sport had been boxing–but he knew enough to seek out good coaching for his son. And when Tony started showing promise as a catcher on the local baseball team, Arch sat him down and explained that if he wanted to be great, he needed to pick one sport or the other.

Tony might have picked baseball–this is Midwestern America in the 1940s, after all. Except Cincinnati had one local tennis hero who stepped in. Bill Talbert was 12 years older than Tony, and he was his country’s best doubles player. He won four men’s doubles titles at Forest Hills, plus another four in mixed with Margaret Osborne. Talbert saved his best tennis for his hometown Tri-State Championships (essentially the same event that is still played in Cinci two weeks before the US Open), where he won the singles title in 1943, 1945, and 1947.

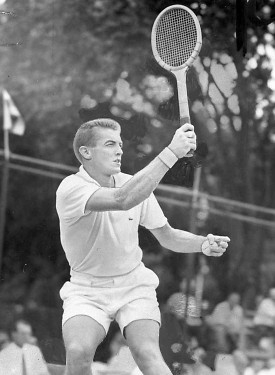

Trabert (right) with Talbert in 1950

By the time he met Tony, Talbert lived in New York City. Still, he became a mentor to the young player, and when Tony’s game was ready, in 1950, Talbert took him to Europe as his doubles partner. The Cincinnatians were nearly unbeatable, winning the Italian Championships and adding a crown at the French, the first of Tony’s five major doubles titles.

Trabert was overmatched on the singles court, especially on the unfamiliar grass at Wimbledon. But that first European trip was enough to convince the 19-year-old that he belonged.

* * *

Even without Talbert’s intervention, Tony might have found his way to tennis stardom. He opted to stay close to home for college, attending the University of Cincinnati. College tennis was the one thing that could put a non-Californian on equal terms with the Golden Staters, as it offered promising athletes coaching, time to practice, and a few extra years to work on their games.

All of the non-Californians to win a national title between Tilden and the Open era–Wilmer Allison, McNeill, Trabert, and Vic Seixas–played college ball. Parker didn’t, but in addition to his time in Los Angeles, he was virtually adopted by Mercer Beasley, who coached the tennis team at Tulane at the same time he developed Parker.

While the University of Cincinnati was no tennis powerhouse, it gave Trabert that extra development time. Tony also took advantage of his two years as a UC Bearcat to get into better tennis shape. He was built more like a football halfback than a racket wielder, and at six-feet-one-inches tall, it took consistent work to stay at his playing weight of 185 pounds. He played for the nationally-competitive UC basketball team, discovering that hoops training helped his endurance and quickness.

After two years of college, Trabert had reason to feel good about his game. He reached the quarter-finals at Forest Hills, where he pushed Australian star Frank Sedgman to five sets. Sedgman would win the tournament, and none of his other opponents managed to take a single set from him. Tony was also a key member of the 1951 Davis Cup team, winning four singles and three doubles rubbers to put the Americans in the Challenge Round against Australia. He was limited to doubles duty (behind Ted Schroeder, who played badly in his final Cup appearance), but impressed the Aussies nonetheless.

The young man from Cincinnati was one of the brightest hopes for US amateur tennis. But with the Korean War raging, Tony’s local draft board received a few letters suggesting his university studies were just a sham to keep him out of the service. He enlisted in the navy–he felt “forced” to, even if he wasn’t drafted–and spent much of the next two years on an aircraft carrier in the Pacific, trying to have serious conversations with sailors who preferred to swap comic books.

* * *

The path to Trabert’s breakthrough season in 1953 was anything but straightforward. He grew up in a tennis backwater, went to a school without much of a tennis program, and missed tournament play for months at a time.

Somehow, he came back from his time at sea playing better than ever before. He won 14 tournaments in 1953, frequently squaring off with Seixas or the 18-year-old Ken Rosewall. He reached a new peak at the US National Championships, the sole major he was able to enter that year. He didn’t drop a set in his six matches, blasting past Patty and Rosewall, then Seixas in a lopsided final. Rosewall was the only one of the three who even managed to reach 5-all in a set against him.

Trabert’s body, conditioned by basketball and the navy, dispatched shots that mere tennis players could barely handle. The South African player Abe Segal saw Tony win the Wimbledon final two years later against Kurt Nielsen, and he could describe the Trabert game only in military terms. “It was like a tank moving infantry … Trabert was driving the tank. Nielsen machine-gunned him but the bullets just bounced off!”

Tony wasn’t the first big man to win tennis matches with powerful shots. But he might have been the smartest big man ever to play the game. In the late 1970s, Jack Kramer rated Trabert one of his top 21 players of all time. He wrote, “Trabert had only a few top shots–backhand, backhand volley, overhead–but what he lacked in his strokes and in his mobility, he made up in his head.”

Trabert’s tactical savvy even went so far as to know when not to go big. Writer Joel Drucker went to one of Tony’s tennis camps as a kid, and Trabert gave him a suggestion for an upcoming match. “That guy’s return isn’t that good, so just serve your second serve first and get in quick. That’s how I beat Seixas at Forest Hills.”

He could bludgeon an opponent, sure. Even worse, he could beat you without unleashing the full force of his weaponry.

* * *

Unfortunately, Trabert spent much of 1954 at war with himself.

It started a few days before the end of the year, as the American team once again attempted to prise away the Davis Cup from the Australians. Tony’s teammate Vic Seixas wasn’t playing well, but Trabert was in form, and he fully expected to win both of his singles matches.

Instead, he collided with an in-form Lew Hoad, who saved the Aussies from a 2-1 deficit on the final day in a dramatic five-setter. The crowd of 17,500 was vociferously pro-Australia, of course. Trabert finally lost his cool late in the fifth set. He missed a serve, Hoad smacked the ball back, and the crowd cheered–thinking it was a return winner. Tony thought they were applauding his service fault, and he criticized the home crowd for it after the match.

He later admitted his mistake, but at the Australian Championships a few weeks later, he lost any remaining fans Down Under. He crashed out in the second round to Aussie vet John Bromwich, when once again the crowd got on his nerves. Bromwich lost the first two sets, 6-1, 6-1, then went on a tear. The crowd that had remained mostly silent for two sets came alive as the local man evened things up. Tony couldn’t take it any more, and he tanked the final set against a 35-year-old he should’ve easily beaten.

Trabert bounced back well enough to win the French Championships. Unlike Angelenos, who grew up playing on asphalt courts, Cincinnatians learned to play on clay. Unusually for the day, Tony hit his backhand with heavy topspin. It helped, too, that he avoided the savviest of the Europeans. From the third round to the final, he faced two Australians and three Californians.

A distracted Tony Trabert in 1954

It was hardly a terrible season. He lost a five-setter to Rosewall in the Wimbledon semi-finals and picked up a couple of smaller titles. But his 1953 campaign had set a high bar that he was obviously failing to clear.

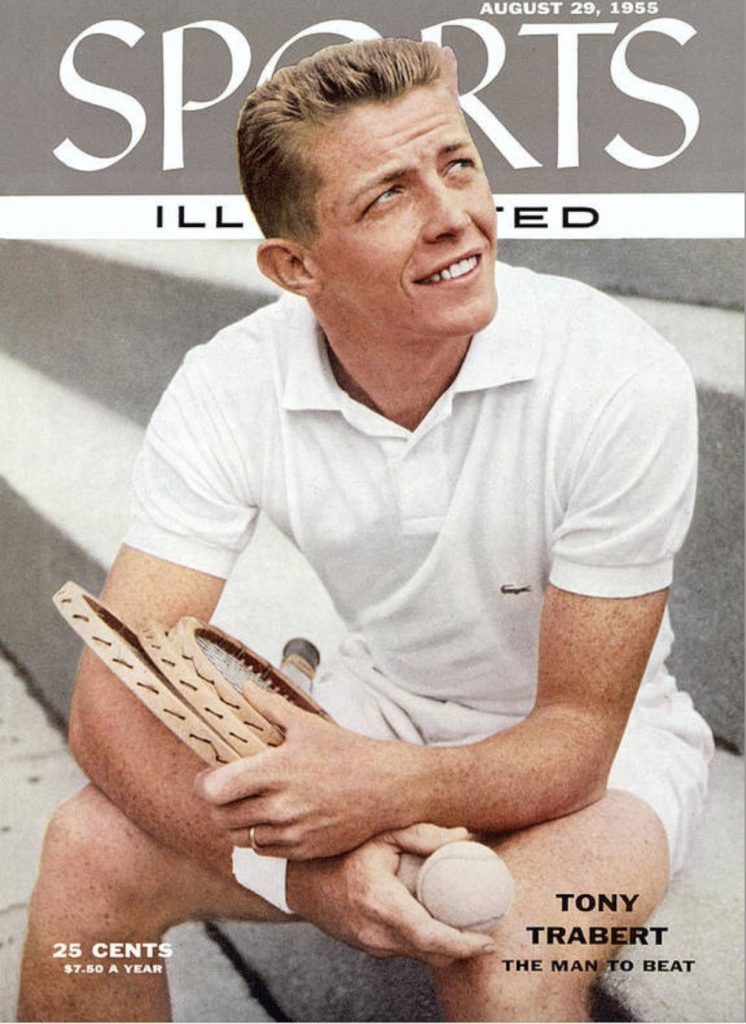

Trabert’s old mentor, Bill Talbert, asked the question in Sports Illustrated in August: “What’s the matter with Tony Trabert?” Jack Kramer, who kept an eye on Tony as a potential pro, thought he knew the answer:

One trouble with Tony is that he’s not as good as he thinks he is. He’s got to quit looking for alibis, and work hard to improve his game. Another thing—he’s got to toughen up his hide. A great champion can’t let himself be upset by a bad call or a heckler. Finally, he’s got to eat, sleep and live tennis. You can’t do this if you’re worrying about outside problems.

That’s a harsh assessment of a player who had won a title and reached a semi-final in last two majors, but Trabert’s performance at Forest Hills bore out the judgment. As the top seed and defending champion, he lost in the quarter-finals to the streaky Australian Rex Hartwig.

* * *

Kramer mentioned “outside problems.” What else did Trabert have on his mind?

In 1953, he met Shauna Wood–Miss Utah, no less–and they were soon married. He found a sales job that allowed him to take advantage of his travel schedule and wouldn’t get too much in the way of his tennis. So Tony’s life was more complicated than that of the typical discharged sailor.

That might have been enough to distract him from his game. But in the eyes of some of his contemporaries, Trabert was unhealthily focused on a pro contract. Kramer–the man who would sign him–probably knew this. Young Australians were in no hurry to turn pro, as their federation would support them financially in ways that were against the rules in the States. Tony, on the other hand, knew he probably had a brief window as a top gate attraction, and he didn’t want to miss it.

While his 1954 season wasn’t good enough, it proved to be the exception. His 1955 campaign–“The New Tony Trabert” in another Talbert article for SI–was the outstanding single-year performance of the decade.

Again, the season effectively began in the final days of 1954 and the Davis Cup Challenge Round. This time, Trabert got the better of Hoad, and the Americans won the first three rubbers to bring back the trophy. He lost to Rosewall in the Australian Championships–his last defeat as an amateur at a major. As a consolation prize, he and Seixas followed up their Davis Cup triumph with a doubles title over Hoad and Rosewall.

Trabert would play 109 singles matches in 1955. The loss to Rosewall was one of only five defeats.

He told Sports Illustrated in August, “I never have–or never would–admit to a weakness, because I don’t think I have a particular weakness.”

That year, his rivals were forced to agree. He had never been particularly deft with low volleys, so he simply crowded the net more, racking up points with high volleys. As he had in 1953, he often took a bit off the serve, so as to hit fewer seconds. He became increasingly aggressive on the return, as well. The pressure on his opponent was relentless.

Trabert defended his title at the French, beating Swedish clay-court specialist Sven Davidson. He tacked on another doubles title when he and Seixas defeated a pair of Italians. At Wimbledon, Tony turned his howitzer on Kurt Nielsen. And at Forest Hills, he avenged his loss in Australia, defeating Ken Rosewall.

At Wimbledon, he won the title without losing a single set. He was just as untouchable at the US Nationals. Trabert was clearly the best amateur in the game–but not for long. Kramer signed him for a $75,000 guarantee, and by the end of the year, he was on the road, facing off in a pro tennis showdown against Richard “Pancho” González.

* * *

Trabert had a solid, if not great, professional career. He wasn’t as good as González–no one was, especially on fast indoor courts. But Tony’s aggressive game kept the scores respectable. In a series of 100 matches, Trabert won a quarter of them.

He continued to play pro tournaments until the early 1960s, and he took charge of Kramer’s European operation in 1960. After a spell away from tennis, he returned as a television commentator, a plain-spoken yet authoritative voice over the air.

When Michael Chang won at Roland Garros in 1989, he was the first American champion there since Trabert took his titles in 1954 and 1955. Tony saw it live, calling the match for Australian TV.

By then, Trabert was the consummate tennis insider. He had captained winning Davis Cup teams and served as president of the Tennis Hall of Fame. Not bad for a husky kid from Cincinnati, Ohio.