In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

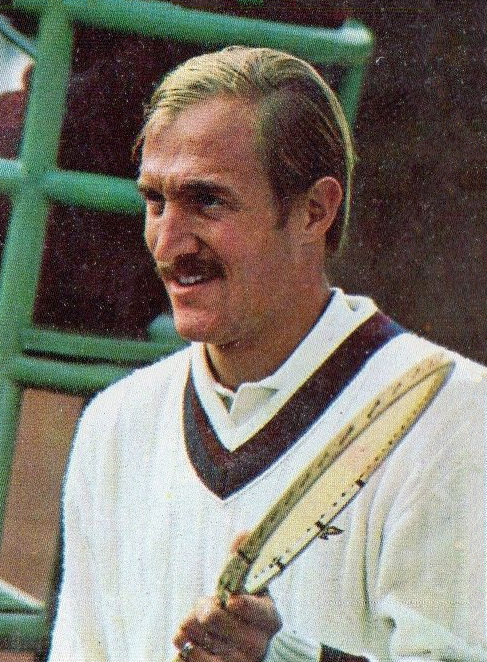

Stan Smith [USA]Born: 14 December 1946

Career: 1964-83

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1971)

Peak Elo rating: 2,248 (1st place, 1973)

Major singles titles: 2

Total singles titles: 64

* * *

Stan Smith’s first love was basketball. Even while Pancho Segura was turning him into a junior tennis champion on the public courts of Pasadena, he continued playing hoops. Baseball and football, too. He played on his high school basketball team until his senior year, when it was finally impossible to pursue more than one sport.

It was always clear where his sporting future laid, even as he grew to six-feet-four-inches tall. Journalists tended to make too much of his time as a hoopster, and he joked in 1972, “[T]he better I get in tennis, the better I become in basketball. If I ever win at Wimbledon, I think they’ll make me an All-American in basketball.”

The scribes who sought to explain Smith to their readers talked about basketball for a reason. Stan was, first and foremost, a team player. By the end of his career, in the early 1980s, the collective aspect of tennis had been obliterated. In an individual sport where everyone was competing for the same lucrative prizes, there was too much at stake.

But Smith’s career was defined by his teams. He played college tennis at USC, winning national singles titles and doubles championships with Bob Lutz. The 1967 Trojan squad, led by coach George Toley, was one of the best of all time. Toley had spotted Stan at the Los Angeles Tennis Club and given him a scholarship, betting on the big kid’s raw talent.

From there, Smith earned a place on the United States Davis Cup team. Australia had held the cup since 1964, and Stan was hardly expected to be the man to bring it back. Arthur Ashe and Clark Graebner were in charge of singles; Smith was there, with Lutz, to play doubles.

The USC grads did their job, winning four out of four rubbers in the 1968 campaign. Ashe and Graebner won their singles matches in the Challenge Round against Australia to bring back the trophy. Yes, it was a depleted Australian team–the country’s biggest stars were ruled ineligible because of their professional standing. But there are no asterisks in tennis.

* * *

The American squad beat all comers for five years running. Smith, more than anyone else, ensured that his country held on to tennis’s most coveted trophy. The main challenge to US dominance was the Romanian team of Ilie Năstase and Ion Țiriac.

Năstase was the most mercurial of stars, a flashy shotmaker who could embarrass you for a set, then lose interest and let the match go in thirty minutes. Țiriac had none of his teammate’s talent, but he made up for it with tactical savvy and gamesmanship that occasionally crossed over into outright cheating. The “Brașov Bulldozer” had played ice hockey for Romania in the 1964 Olympics, and I suspect he was the team’s enforcer. He also played rugby, because of course he did.

The only way to beat the Romanians was to ignore their antics. Fortunately for the American side, Stan Smith was the most unflappable of them all.

Even as a junior, Stan realized that he was unaffected by the match pressure that caused his rivals to crumble. He was poker-faced on court. His gestures on court were limited to the nervous tic of brushing back his hair between points. At his most demonstrative, he would fix his hair a bit more slowly.

In contrast to characters like Năstase and Jimmy Connors, Smith was a throwback. Michael Mewshaw offered a sketch in his book, Short Circuit:

Tall, blond, and regally slim, he is the sort of player Wimbledon loves. He has the stiff upper lip and proud carriage of a Grenadier Guard, never complaining, never responding to success or adversity with much more than a bemused smile.

For Stan, it went back to his grounding in team sports. “You don’t see basketball or football players getting upset at themselves and throwing tantrums,” he said. (This was more accurate in 1972!) He recognized the benefit of his late start in tennis, which allowed him to become both an all-around athlete and an adult with a perspective that extended beyond the locker room.

His first five years on tour would put that perspective to the test.

* * *

The first US-Romania showdown was in 1969. The American defending champs set up shop in Cleveland, where they would force the Europeans to play on a fast hard court. The visitors were realistic about their chances. They figured they could win two of the five points–that is, the pair of singles matches against the newly-promoted Smith.

Instead, the 22-year-old American won every match he played. He took on Țiriac in the second rubber, and came back from a two-sets-to-one deficit to win. Frank Deford wrote for Sports Illustrated that the Romanian was “complaining, glowering, stalking and weaving like a bull at bay.” Smith just focused on getting his serve in, and he held off the Brașov Bulldozer.

Smith and Lutz secured the championship with a doubles win the following day. The reverse singles rubbers didn’t count, but the fans still got their money’s worth. Stan had lost to Năstase in the second round of the US Open just a few weeks before. The two men would ultimately face off 18 times in a 13-year span, reaching a fifth set on five memorable occasions. This was the day that Smith made it clear he could hold his own. He upset the top Romanian in an 11-9 fifth set.

Stan would tell Tennis magazine in 2016, “The team thing really affects you. You don’t want to let them down. It’s not just the country. It gets a little more personal at the point. Your result is as a team, so you wanna see the other guy win.”

He watched the “other guy”–in this case, Cliff Richey–win in the Challenge Round against West Germany in 1970. (Australia was still forced to field a non-competitive squad of “two koala bears and a wallaby,” as Deford put it.) Smith was limited to doubles duty. Once again, he and Lutz scored the decisive point with a straight-set win against the visitors.

When the West Germans came to Cleveland, Smith was still flying under the radar, an obviously skilled doubles player but no more than the third-best American on the singles court. Almost immediately afterward, his reputation began to soar. He opened November in Stockholm, where he upset Ashe and Ken Rosewall, the top two seeds, for the title. A month later, he beat Rosewall and Rod Laver to win the year-end Masters championship. His days as the Davis Cup doubles specialist were over.

* * *

For an athlete willing to throw his weight behind the collective, Stan was surprisingly standoffish. He teamed with Lutz for years, winning doubles titles and rooming with him on the road. But Lutz said, “[W]e hardly knew each other…. I only met him on the court.”

Journalist Richard Evans was one of many who felt that Lutz was the more naturally talented of the pair. He just didn’t work as hard. Few players did. Early on, Smith’s independence had a whiff of superiority to it, but in time, Lutz and others realized that Stan was simply going to do his own thing. When a group went out of the town, that might mean he stayed at the hotel to jump rope.

In 1971, the extra work began to pay off. Technically, he was a corporal in the US Army, but the military saw his public relations value. His tournament schedule was barely affected. After a surprisingly successful clay court campaign–he won a title and reached a career-best quarter-final at Roland Garros–he beat John Newcombe at Queen’s Club. He went into Wimbledon as the 4th seed and reached the championship round. He nearly upset Newcombe again, losing to the Australian in the fifth set.

Smith took the final step at the US Open. His career at Forest Hills had begun with some nasty draws: Tony Roche was his opening-round opponent in 1968, and he faced Năstase in the second round in 1969. Finally the tennis gods were ready to repay him.

Stan beat compatriot Marty Riessen and 4th seed Tom Okker to reach the final. Waiting there was the Czech Jan Kodeš, mostly known at that time as a threat on clay. Kodeš had knocked out Newcombe, the top seed, in the first round and followed it up with a five-set victory over Ashe in the semis.

With the help of his childhood coach Segura, Smith went in with a game plan. He served well, threatened the weaker Kodeš service, and kept the Czech player honest with lobs when he crept too close to the net. At age 24, he had his first major singles title.

The Davis Cup defense was, by comparison, a walk in the park. The Americans shifted venues to Charlotte, where they welcomed the Romanians with the slightly less US-biased green clay. It didn’t matter. Smith straight-setted Năstase in the opener. With a new partner, the young and inconsistent Erik van Dillen, he lost the doubles. But he kept his streak of decisive victories alive. In the fourth rubber, he dispatched Țiriac in three, sealing the trophy with a 6-0 final set.

* * *

In 1983, Smith proclaimed, “A truly great player should be able to win on all surfaces.” By that standard, Stan would establish himself among the legends of the game in 1972.

The American Davis Cup defense would be more complicated than usual. The tournament finally gave up the archaic Challenge Round format, in which the previous winner sat out until the rest of the field had been whittled down to one. To win a fifth-straight championship, the US side would need to work through the Americas zone and play four ties just to earn a place in the title round.

Smith remained a stalwart for the cause, winning all seven matches he played in the first three ties. In the meantime, he solidified his status as one of the world’s best. He opened the season by winning four tournaments in a row, two of them in finals against Năstase and another with a five-set victory over the fast-improving 19-year-old Jimmy Connors.

He failed to defend his Queen’s Club title, perhaps distracted by the news that was roiling the tennis world. We tend to remember the 1973 Wimbledon boycott, in which 81 men skipped the Championships over an internecine dispute between the International Lawn Tennis Federation (ILTF) and the fledgling players union. But the 1972 tournament had every bit as much controversy.

Few things went smoothly at Wimbledon in 1972

That year, the ILTF banned the pros under contract to World Championship Tennis (WCT), the richest of the professional circuits. It was the same dispute that had kept the best Australians out of Davis Cup competition. (It was also the reason why Smith now partnered van Dillen. Lutz had signed up with WCT, making himself ineligible for Davis Cup play.) The details of the conflict are murky to a modern reader, but the broad strokes are familiar to anyone who watched tournaments jockey for calendar position amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Both sides wanted prime spots on the schedule, access to the best players, and full control of as much of the sport as possible. In other words, it boiled down to money, money, and money.

For Stan Smith, it meant that defending champion Newcombe–and a host of others–would spend much of the Wimbledon fortnight at the WCT event in St. Louis instead. Smith, along with Năstase, Kodeš, and others, was an “independent” pro, unsullied by any direct financial link to the competing tour. He entered Wimbledon as the top seed, unthreatened by Newcombe, not to mention Laver, Rosewall, and Ashe.

It was impossible to ignore the decimated draw, but Smith fell back on his usual strategy of blocking out everything that didn’t directly affect his tennis. “You don’t try to lose just because all the best players aren’t here. The subject isn’t even worth my time. This is still the greatest tournament in the world, and the pros know it. For me, this championship would be the pinnacle.”

Or as a less serious competitor put it, it was still Wimbledon, “even if they threw out everybody and seeded two monkeys onto center court.”

Stan beat Kodeš in the semi-finals for yet another showdown with Năstase, who had lost only two sets en route to the final. It might not have been the championship match that the tournament would have delivered with WCT stars on hand, but the clash between top-seed Smith and second-seed Năstase was everything the All-England Club could’ve hoped for.

It was the 9th meeting between the two men. Each had won four: Smith with the Davis Cup victories, and Năstase with successes at Roland Garros and in the 1971 year-end Masters final. Still, the American was confident. He told reporters, “If I have to, I can always go to my guts to beat this guy.”

He had to. The Romanian was brilliant, putting service returns on Smith’s shoetops and–most remarkably of all–generally keeping his emotions in check. Stan could only wait for his opponent to falter. With what he called “80 percent guts and a little luck,” he came through, converting his fourth match point on a missed Năstase smash to win, 4-6, 6-3, 6-3, 4-6, 7-5.

The lengthy New York Times recap of the match said nothing of the absent stars. There are no asterisks in tennis.

* * *

The Wimbledon final was, of course, played on grass. The US Davis Cup team had three rounds remaining in their 1972 campaign, and all three would be played on clay.

First they went to Santiago, Chile, where they made quick work of the hosts. Smith won three matches, including a five-set doubles victory alongside van Dillen. Two weeks later, they were in Barcelona for another dose of the red stuff. Stan lost to Andres Gimeno in the opening match. But by now, you can probably write the next sentence yourself. He and van Dillen won the doubles, and in a deciding fifth rubber, Smith straight-setted Juan Gisbert.

Waiting in the championship round: Romania. Unlike in 1969 and 1971, the Davis Cup would be decided in Bucharest.

Back in 1969, Țiriac had fumed after he failed to figure out the shower faucet in a Cleveland locker room and suffered through a cold mid-match shower. The Romanians, hosting a Cup final behind the Iron Curtain for the first time in history, aimed to pay back every slight, real and imagined.

The surface, in particular, was chosen to ensure a US defeat. Țiriac said, “The U.S. players not like the soft stuff,” he said. “Wait till they see ours. Godzilla, he feel like he serving on the beach.”

“Godzilla” was Țiriac’s nickname for Stan Smith.

The crowd was rowdy, the Romanian linesmen were blatantly biased, and the Americans were accompanied around town by 20 “translators”–bulky men with guns and conspicuously absent language skills. Țiriac, the master gamesman, pushed his advantages to the limit, leaving Tom Gorman–the second US singles player behind Smith–in tears. The Romanian antics were so bad that after the first two matches, American captain Dennis Ralston called it “the most disgraceful day in the history of the Davis Cup.”

Few men could excel under such conditions. Fortunately the Americans had just such a player in Smith.

The tie opened with a rematch of the Wimbledon final. Năstase held his own for 18 games in the opening set, but he was finally thrown off his game by an unexpected double fault call. Smith broke to get on the board first, 11-9. For all of his bluster–Năstase had said the Romanians were 10-1 favorites–the Romanian star simply went away.

Or maybe Smith slammed the door. Herbert Warren Wind described the American’s dominance for the last two sets of the match:

He served with explosive power, he blasted Năstase’s serve for outright winners, and he ranged swiftly around the forecourt, hitting one biting volley after another. I have never seen a man hit his shots on clay with the pace that Smith maintained in winning the next two sets, 6-2 and 6-3. He played exactly as if he were playing on grass–fast grass.

After Țiriac beat Gorman to even the tie, it was van Dillen’s turn to shine. Alongside the ever-steady Smith, he defied the hostile crowd and turned in the match of his life. The Americans won the doubles, 6-2, 6-0, 6-3.

The visitors led, two matches to one, and once again, Stan was in position to finish the job. It wasn’t easy. Țiriac simply refused to give in, and he had help. The linesmen were so bad that after three blatant mistakes in the same game, Ralston was able to get one of them removed. On another occasion, Smith hit a return winner off a Țiriac first serve, only to hear the service line judge pipe up with a belated “out” call. That gave the Romanian a second chance.

After splitting four long and winding sets, Smith was too calm, and his game was too strong for the wily man from Brașov. He hit an ace to open the fifth, and from there, he played what Wind called “an almost perfect set.” He dropped a 6-0 frame on Țiriac, just as he had in Charlotte the year before. The Americans won their fifth straight Davis Cup.

* * *

Thus ends the usual list of Smith’s outstanding accomplishments. In the space of 14 months, he won two singles majors and led his country to two Davis Cup titles.

Yet his best tennis was still to come. He joined the WCT circuit in late 1972 after completing his military obligations. He won his first tournament among the contract pros in Los Angeles a few weeks before the trip to Bucharest.

The level of competition took some getting used to, and he lost matches in early 1973 to Laver and Rosewall. He quickly adapted and went on a tear beginning in March. He won four consecutive tournaments, beating Laver and Richey three times apiece. A month later, he and Lutz won the WCT World Doubles title in Montreal, and Smith followed it up with a victory at the season-ending championship in singles in Dallas. He overcame Laver in the semis and Ashe in the final.

Even before the Dallas final, Stan was confident: “I’ve always claimed Laver was the best. Today is the first time I feel comfortable in saying that maybe I am.”

The ATP wouldn’t roll out its ranking system for another few months, but my Elo ratings support Smith’s contention. They put him at the top of the table midway through his four-tournament run. After Dallas, he had opened up a meaningful 50-point lead over Laver and Năstase.

He later said, “I was probably playing the best tennis of my career right about then.” A couple of months later, he would even win a title on European clay, beating Manuel Orantes and a young Björn Borg in Båstad.

But in that summer of 1973, he wouldn’t defend his Wimbledon title. This time, he found himself on the side of the boycotters. The ILTF suspended Yugoslavian player Niki Pilić for skipping a Davis Cup tie, and the players union–the ATP–took his side. A compromise was within reach: If the ILTF backed down, Pilić was willing to withdraw to let everyone save face. But Wimbledon didn’t take the boycott threat seriously, and Smith was one of 81 men who stood on their principles instead of chasing the most coveted title in tennis.

* * *

It was an unlucky break. Smith never again recovered the form that won him so many laurels in a such a short span. Even the Davis Cup slipped away. The Australians were able to deploy their best players again in 1973, and the duo of Laver and Newcombe handed Smith three defeats in a final-round sweep.

But Stan was rarely one to complain. He has always recognized the role that luck played in his career. He grew up in the tennis hotbed of Southern California, and met Segura at exactly the right age to start him on the path to stardom. A few years later, he secured the final tennis scholarship that USC had to offer that year.

Upon graduation, his timing couldn’t have been better. He and Lutz won the doubles title in their first appearance at Forest Hills, claiming thousands of dollars in prize money that had never been available before. Smith wasn’t drafted into the military until long after he was eligible, and even then, he was able to continue playing tournament tennis.

And the biggest break of all: Stan Smith became a shoe. When Adidas realized that a stylish shoe called the “Haillet”–after a French player–wouldn’t have much traction in America, they turned to Stan. 100 million pairs later, Smith is a wealthy man, and his name is known far more widely than that of the typical Wimbledon champion.

The ultimate irony is that it’s Stan’s name–and only his–on some of the world’s most recognizable footwear. Sure, endorsements don’t really work any other way. But of all the tennis stars to parlay their success into lucrative name recognition, Smith is the one who, in his glory days, tended to deflect attention.

A few big-name players ignored the boycott and entered Wimbledon in 1973. But for the defending champion, it was never an option. It would have been a betrayal of his friends and colleagues, not to mention a blow to player’s rights in the crucial early days of Open tennis. As someone with Stan’s track record could have predicted, luck would eventually tilt back in his favor. He missed his chance to win back-to-back Wimbledon titles. But the first championship was enough for Adidas to make him an icon.