In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Andy Roddick [USA]Born: 30 August 1982

Career: 2001-12

Plays: Right-handed (two-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (2003)

Peak Elo rating: 2,181 (1st place, 2003)

Major singles titles: 1

Total singles titles: 32

* * *

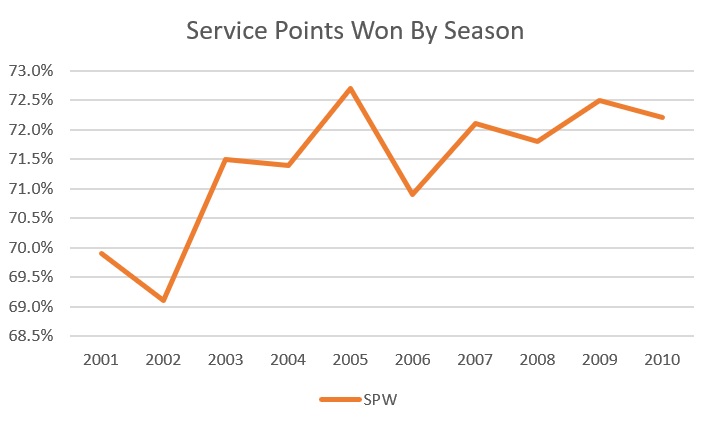

Pretend for a moment that you don’t know who I’m writing about today. Take a look at this graph of service points won, for each year over a span of a decade, and try to pick out the player’s best season:

2005 sticks out, both because the mark of 72.7% is the highest of any season in the span, and because it is considerably better than the years immediately before and after. As far as multi-year spans are concerned, the last four seasons are the best.

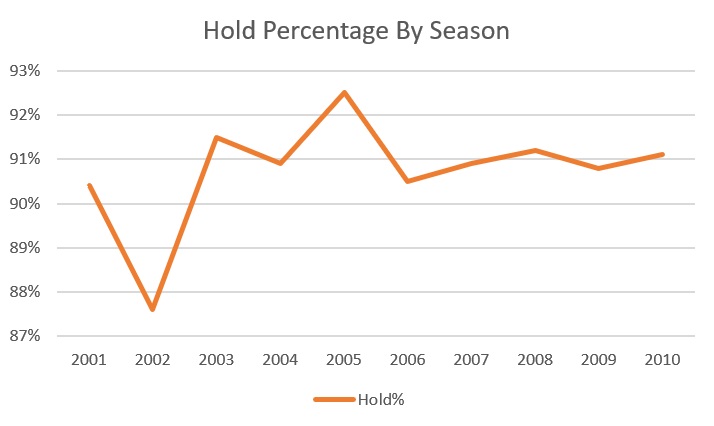

Service points won can be a bit deceiving, because a player might have a particular good or bad stretch in clutch situations. A serve-related metric that is more closely tied to match results is hold percentage. Here is the same player, over the same decade, measured by the rate at which he held serve:

This plot tells a similar story, also highlighting a peak season in 2005. There’s not much change from year to year, with seven of the ten years within a half percentage point of 91%. That, by the way, is incredibly good. John Isner’s career average is 91.8%. Even the 2002 outlier below 88% is an outstanding hold percentage–this is a guy who was consistently very difficult to break.

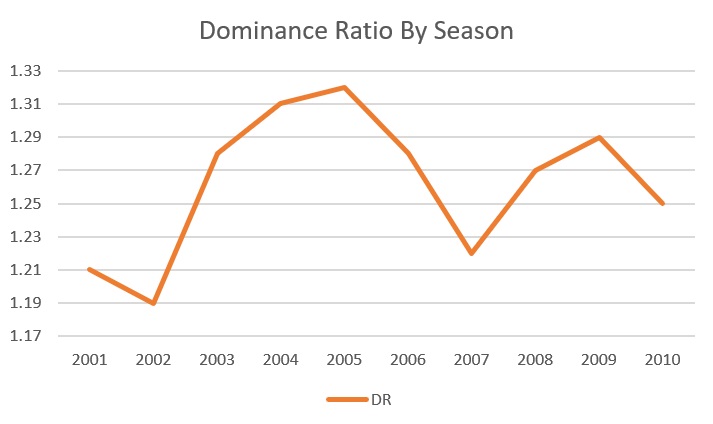

One more graph. I’ve ignored return points so far, partly because this player’s game was so serve-dominated, and partly because the year-to-year changes in return points are about as consistent as his serve performance. Still, it’s worth seeing the whole picture.

The Dominance Ratio stat expresses the ratio of return points won to serve points lost, so it takes both sides of the ball into account. A player who wins half of their points will have a DR around 1.0. 1.2 is very good, and 1.3 is usually good for a place in the top five, if not better. Here is the decade in question by DR:

The 2004 season now looks almost as good as the 2005 peak, with the other years noticeably lower. Setting aside the weak campaign of 2007, when our player won only 34% of return points, the entire 2003-10 span, or at least 2003-09, is quite strong.

* * *

So yes, of course, all of these numbers belong to Andy Roddick. The same Andy Roddick whose on-court career is best remembered for one great season, when he won the US Open and finished the year as number one on the ATP computer. That year was 2005 2004 2003.

Whatever the stats say about it, 2003 was a memorable campaign for the American, who turned 21 years old in August of that year. He reached his first major semi-final in Australia, then after winning titles on both clay and grass, he appeared in his second slam semi at Wimbledon. He was nearly unbeatable on North American hard courts, winning four titles in the course of a five-tournament span between Indianapolis in July and the US Open in September. He even upset Roger Federer in Montreal.

The season began with Roddick clinging to a spot at the outer fringe of the top ten. He came to New York as the fourth seed, he left it as the newly-minted number two in the world rankings, and he ascended to number one by the end of the season. The sky was the limit for the hyperactive Texan with the electric serve.

Then, at the 2004 Australian Open, Roddick lost in the quarters to Marat Safin. Federer won the tournament and knocked the American from his ranking perch. You might have heard about what happened next. 237 weeks later, when Federer finally lost his death grip on the top spot, Roddick was no longer seriously in the mix. Rafael Nadal became the new number one in August of 2008, and Roddick was ranked eighth.

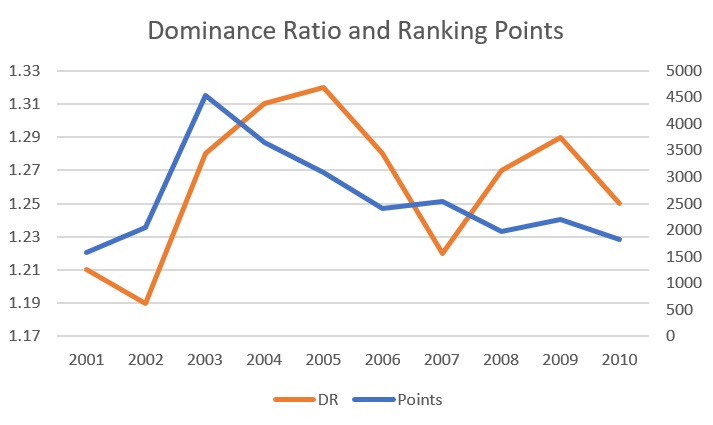

Let me show you the Dominance Ratio graph again, this time superimposed with Roddick’s ATP ranking points at the end of each year. (The points system changed between 2008 and 2009, so the 2009-10 points are adjusted accordingly.) His DR fluctuated, but after 2003, the points went in only one direction:

The stats–at least the ones I’ve shown you thus far–clearly don’t tell the entire story.

* * *

At the point-by-point level, Roddick improved on his breakout 2003 season, and his peak years were in 2004 and 2005. By contrast, the rankings–not to mention the all-important grand slam count–suggest that things went downhill more or less immediately after he straight-setted Juan Carlos Ferrero to secure his sole major trophy.

Which is right? The stats might be fooling us, and his 2004 and 2005 seasons (and beyond) might not be as good as they look. Alternatively, if the rankings are the ones telling a misleading story, we may be underrating a player with unfortunate timing.

There are many possible explanations for the clash of narratives. Here are the three I find most compelling:

- He was lucky. That is, he didn’t really deserve the number one ranking (and possibly even the US Open title) in 2003.

- He didn’t get worse, but he field overtook him. To put it another way: Federer happened.

- His schedule became more favorable, possibly because he chose to play fewer events on clay, or because he opted to play tournaments with weaker fields. If that is true, his stats from those seasons may be artificially inflated.

Let’s dig into each one.

He was lucky

How you feel about this explanation depends on lot on your take on deciding-set tiebreaks. Roddick played 42 of them in his career, winning 27, for a respectable 64% success rate. His overall career tiebreak winning percentage was a similarly strong 62%.

In 2003, he played eight third-set tiebreaks, winning six of them. One of those–a loss to Rainer Schuettler–came at the season-ending Masters Cup after he had secured the number one ranking–so the more relevant group of matches are seven final-set shootouts, of which he lost only one.

Most of the nailbiters had a significant impact on Roddick’s ranking point total, either because they occurred in an important match, or they saved him from losing early in an event where he went on to greater success. He just barely edged Hyung-taik Lee in the Memphis second round, then went on to reach the final. He won a third-set tiebreak (8-6, no less) from Andre Agassi in the Queen’s Club semi-final, then won the final the next day. He narrowly escaped a first-round defeat in Indianapolis to 101st-ranked Cyril Saulnier, and he went on to win the tournament.

Most important of all: He needed a third-set breaker to beat Federer in Montreal (where he won the title), and he won a squeaker against Mardy Fish, 4-6, 7-6(3), 7-6(4), in the Cincinnati final.

And then there was the US Open semi-final against David Nalbandian. The third-set tiebreak didn’t decide the outcome, since it was a best-of-five-set match. But the shootout was every bit as crucial as the ones against Federer and Fish. The Argentine won the first two sets and earned a match point on Roddick’s serve at 5-6 in the breaker. Nalbandian failed to get either of his next two returns back in play, lost the tiebreak 9-7, and collapsed, dropping the final two sets, 6-1, 6-3.

“Luck” may be the wrong word here. A better way to put it might be that there was a mismatch between his point-level stats and his overall performance. In Dominance Ratio terms, a victory via deciding-set tiebreak doesn’t look very good. To take an extreme example, Roddick’s DR in the win over Saulnier was a below-average 0.84, a rate that almost always means that the player lost.

The mismatch leaves us with a new unanswered question. Do Roddick’s point-level stats underestimate him, because he could be counted on to win a lot of those close matches? Or was he bound to regress to the mean?

The answer is probably some of both. A big server is always going to have some matches decided by narrow margins, but he can’t depend on winning so many of them. This explanation accounts in part for the difference between Roddick’s 2003 and, say, 2006, when his full-season DR was the same, but he won three of six deciding-set breakers, not six of eight. But it doesn’t explain the ranking-point drop-off between 2003 and 2004. For that, we need another factor.

Federer happened.

In 2003, Roddick won 72 matches and lost 19. In 2004, he won 74 and lost 18. Like the charts I started with, these numbers suggest that he was every bit as good–and possibly a bit better–in the latter season.

But in that second season, Federer also won 74 matches… and he lost 6. It was the first year that one man won three of the four majors since Mat Wilander did it in 1988.

Roddick didn’t stand a chance. When the American won his major in September 2003, Federer had beaten him four times in five meetings–and as we’ve seen, the one win required a third-set tiebreak. When Roddick played his first tournament as number one, at the 2003 Masters Cup, Fed knocked him out in the semi-finals. The two men played three more times in 2004, in the Wimbledon final and two other title matches. Roddick managed to win only one set.

Federer, of course, wasn’t going anywhere. Roddick ultimately reached five major finals in his career. The last four all pitted him against Fed, and even though he won a set in three of them–even reaching 14-all in the deciding set at Wimbledon in 2009–he never made it across the line. They faced off 24 times in all, and the Swiss maestro won 21, including an 11-match streak that ran from the 2003 Masters Cup through the same event four years later.

Roddick finished 2004 at number two in the rankings, so had it not been for Federer, he probably would’ve stayed on top.

Still, there’s more to explain. Federer’s presence tells us why Roddick couldn’t stick at number one, but by July of 2006, when the American lost to Andy Murray in the Wimbledon third round and failed to defend finalist points, he dropped out of the top ten entirely. According to the stats, he was still playing well, with a DR of 1.28 that year–the same as what he posted in 2003. But he finished the year ranked behind not just Federer and Rafael Nadal, but also Nikolay Davydenko, James Blake, and Ivan Ljubičić.

His schedule became more favorable

Roddick won 32 career titles, and most of the tournaments he won had a lot in common. More than half were in the United States, and they typically came on fast courts. He won a handful of titles on clay, but three of them were on the fast-playing, artificial surface in Houston. Only one came on European dirt.

Most of his titles came at second-tier events, as well. He beat top-ten opponents in finals only twice, and he earned nine of his trophies with championship-round victories against players ranked outside the top 50.

The theory, then, is that after his first successful years on tour, Roddick’s schedule got “cheaper”–fewer matches on clay (excepting Houston) and more time on court against sub-standard opponents. Both of those changes, if true, would make his statistics look better, but they wouldn’t do much for his ranking.

It’s true that he steadily reduced his time on clay courts. In 2003, he played 21 matches on dirt, 5 of them in Houston. He would never again play double-digit matches on non-Houston clay in a single season, and from 2007 on, he cut out Houston as well.

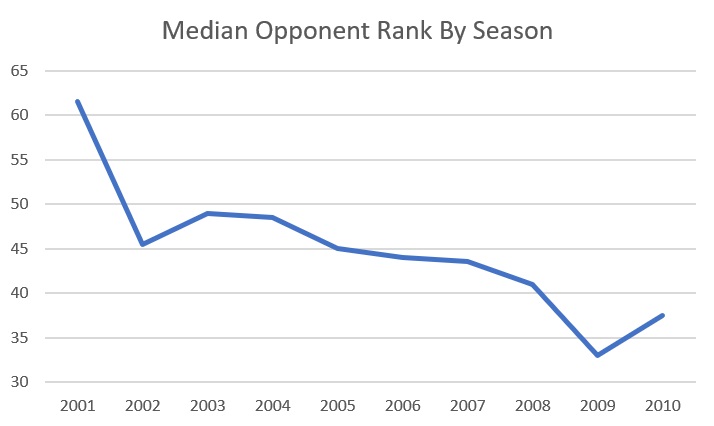

It’s not true, however, that his opponents got worse. Quite the contrary. Here is the median opponent rank for each of his seasons, 2001-10:

In 2003 and 2004, Roddick’s median opponent was ranked just inside the top 50. From 2005 to 2007, his typical opponent was closer to 45th, and it only got tougher from there. On the reasonable assumption that we can use ranking as a proxy for opponent skill, his schedule got tougher throughout the decade, even if he more often played on his preferred surface.

* * *

What are we to make of all of this? If you believe the top-line stats that we started with, Roddick was more or less the same player at the end of the decade–when he ranked 8th on the ATP computer–that he was in 2003. Federer’s arrival derailed any hope that the American would enjoy a second year-end finish at number one, and Roddick fell much further behind than that.

Again, “luck” might not be the right word, but the season that made Roddick number one in 2003 was always going to be difficult to duplicate. His back-to-back Masters titles in Montreal and Cincinnati not only relied on a pair of third-set tiebreaks, but they were also possible because of a field in flux. Federer and Sébastien Grosjean were the only top-tenners Roddick played in the course of the two events, and Ferrero was the only single-digit seed he faced at the US Open.

The rest of the 2003 season previewed the rest of the decade, and not just because his year ended with a defeat at the hands of Federer at the Masters Cup. Roddick lost close matches to Nalbandian and Tim Henman, and he lost a Masters Cup round-robin match to Rainer Schuettler in a third-set tiebreak. He won 36.4% of his return points that year, just above the 36% threshold I’ve defined as the “minimum viable return game” for a would-be elite player.

Roddick spent his entire career hovering around that line, winning 37.5% of return points in 2004 but only 34.0% in 2007. I’m not sure why 36% in particular is the threshold, but it’s extremely rare to find a player in the top five who can’t defend at least that well. Around that number, every match can turn into a close one, and as the men’s field got stronger and stronger throughout Roddick’s career, he never again had the opportunity to string together so many narrow victories.

Over the course of a full career, though, a player with Roddick’s weapons is bound to have a stretch when form, clutch play, and perhaps a bit of luck come together to show what is possible. In 2009, that meant a four-hour heartbreaker of a Wimbledon final against Federer. But in the land of opportunity that was 2003, he posted a series of accomplishments that, all by themselves, make up a solid case for the Hall of Fame.