In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Budge Patty [USA]Born: 11 February 1924

Died: 4 October 2021

Career: 1940-60

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1950)

Peak Elo rating: 1 (1954)

Major singles titles: 2

Total singles titles: 89

* * *

Take a quick glance at the Budge Patty biography and you might think you’ve found the impossible: a mid-century American champion who didn’t come from California. He was born in Fort Smith, Arkansas, in 1924, and after serving in the US Army during World War II, he settled in Paris, working as a travel agent and playing the majority of his tennis on the Continent.

Patty broke the mold, to be sure. Allison Danzig called him the “glamour boy” of men’s tennis, and Harry Hopman likened him to the fashion pioneer Beau Brummel. He always balanced the sport with other interests, and he rarely appeared to be working hard. Tony Trabert joked, “[P]hysical training for him meant breaking his cigarettes in two and then smoking only half the amount.”

He developed into a one-of-a-kind character, an unlikely American in a strong era of American men. But despite the unorthodox biography, his path did, indeed, run through California.

His father died when he was young, and the family moved to Los Angeles. He lived near Pauline Betz–with whom he would win the 1946 French mixed doubles title–and the pair were frequent practice partners. Patty took his first lessons at the Beverly Hills Tennis Club, where he found playing partners and patronage. When his coach, Bill Weissbuch, couldn’t convince him to develop a strong net game, Weissbuch brought in Bill Tilden to show the young man why it was necessary. The aging Tilden beat the youngster, 6-0, 6-0, 6-1.* Message received.

* Patty wrote, “I don’t remember now, but I am sure I must have won my solitary game by hitting four net-cords.”

Budge was born J. Edward Patty, and he gained his nickname when his older brother thought him so lazy–or stubborn, in one rendition–that he wouldn’t budge. On court, however, he proved to be quite flexible. He didn’t grow to his full height until his later teens, so some creativity was required as he won one junior title after another. Hopman wrote,

The ‘slam bang’ big-hitting service and volley game was not for one who was not much higher than the net post, so he studied court-craft and the tactics of visiting stars who were not all-out net-rushers and he experimented in his own way as he progressed.

Even as a six-footer, Patty would always do things his own way.

* * *

Patty won the 1941 and 1942 United States junior titles. The Army drafted him just as he was about to enter the University of Southern California, and when he was sent to Europe for the duration of the war, he was forgotten by American tennis fans.

In his first entry at Forest Hills after the war, in 1946, the 22-year-old Patty quickly reminded them of his promise. He scored the upset of the tournament in the second round, straight-setting Wimbledon champion Yvon Petra. The six-foot-five-inch, big-hitting Frenchman wasn’t accustomed to opponents who would take advantage of a short backswing to return his serve from inside the baseline. In the New York Times, Allison Danzig couldn’t resist punning on the newcomer’s name. Petra had break point to even the third set at 4-all, “But Patty refused to budge.”

He lost in the fourth round to another big man, Bob Falkenburg, but the rest of the circuit was on notice that the suave expatriate was a force to be reckoned with.

Patty would solidify his reputation at Wimbledon the following year. At the 1947 Championships, he pulled through one nail-biter after another, needing five sets to beat Australian Davis Cupper Bill Sidwell in the first round, another five to advance past Atri Madan Mohan in the second, and four to defeat the unheralded Brit Derrick Barton in the third.

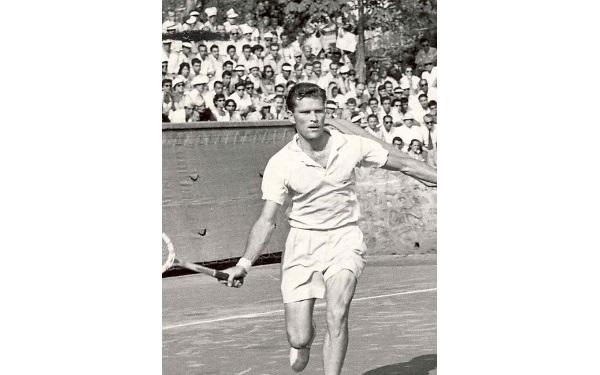

Patty at Wimbledon in 1949

In the fourth round, he recorded the outstanding upset of yet another major. After another five sets, he knocked out second-seeded Australian John Bromwich in a roller-coaster of a match, 6-4, 0-6, 6-4, 1-6, 6-4. Patty’s exhaustion accounts for some of the set scores, as he admitted to throwing the fourth set to save energy. He couldn’t afford to do the same against Jaroslav Drobný in the quarter-finals, falling behind two-sets-to-one after a 9-7 third frame. In the first of many memorable matches against the sixth-seeded Czech, he came through in still another five-setter. No wonder he blamed fatigue for his semi-final loss to fellow American Tom Brown.

Funnily enough, Drobný considered Patty’s (probably legitimate) exhaustion to be gamesmanship. He wrote, “So often during the match he looked near exhaustion, leaning on his racket, sitting down as we changed ends that I took pity on him and allowed my concentration to wander.” Drobný likened his opponent to Ted Schroeder, another five-set master: “Patty is not only an artist on the court but a great match player as well. He … knows what points to win and those that do not matter.”

Another contemporary with praise for Patty’s match-management skills was Jack Kramer. Kramer was not exactly the humblest of champions–decades later, he made a hypothetical list of Wimbledon and Forest Hills champions, had professional players been allowed to compete. In the reconstruction, lifelong amateur Patty lost his 1950 Wimbledon title to–you guessed it–Jack Kramer. Still, Kramer said that Patty’s forehand volley “came close” to the best he’d ever seen, and he credited Budge with an unusual clutch skill:

[T]he strangest competitive stroke was the backhand that belonged to Budge Patty. It was a weak shot, just a little chip. But suddenly on match point, Patty had a fine, firm backhand. He was a helluva match player.

Kramer’s decision to go pro meant that the two men never faced each other after 1946. Drobný wouldn’t be so lucky.

* * *

For the next two years, Patty settled into a life of cosmopolitan comfort in Paris. He reached the semi-finals at Roland Garros in 1948, losing in five sets to Drobný. He made the 1949 final, where Frank Parker out-steadied him. The Wimbledon title, on the other hand, crept further away–he lost to Bromwich in the 1948 quarters, and to Drobný in the third round in 1949.

The losses were still fresh in his mind when he wrote his 1951 autobiography, Tennis My Way: “When the draw is made … the thought that immediately runs through most players’ minds is, ‘I hope I’m not in Drobný’s half.'”

On the Continent, Patty learned, winning wasn’t everything. He explained in his book why he chose to play in Europe. The short answer: “Because it is more amusing.” The longer answer involved money and respect. In the US, a handful of prestigous tournaments held all the power, and they treated players accordingly. Across the Atlantic, a larger number of events competed for a relatively small group of high-profile players, of whom Patty was one. They were willing to pay higher “expenses” to secure the stars.

Plus, European crowds took to the debonair American. Harry Hopman wrote, “[T]he French gallery [went] ‘overboard’ for ‘Pat-tee’ almost as if he were a Cochet, Lacoste or Borotra playing Davis Cup for La Belle France.” In Rome, Patty won over the raucous, partisan Italian crowd when he stopped play mid-way through a point, turned to the crowd, and shouted, “Silencio!”

The American would spend another decade pleasing galleries around the Continent. But in the third-round loss to Drobný at Wimbledon, he threw the fourth set only to discover he didn’t have enough energy for a victorious push in the fifth. “I decided then and there,” he wrote, “that next year I was either going to give myself the chance to play properly or give up tennis altogether.”

* * *

Patty thought himself a changed man, but his new training schedule would get him laughed out of a modern-day clubhouse.

For one thing, the decision he took at Wimbledon in 1949 didn’t exactly spur him into immediate action. He started seriously working out the following May, a few weeks before the French. Only then did he give up smoking. He made sure to get ten hours of sleep every night, and he jogged one to three miles each morning. It was a step in the right direction, but Emil Zátopek he was not.

Somehow, it was enough. At the French, he faced an unexpected quarter-final challenge from Irvin Dorfman, an American who never advanced past the third round at another major. Dorfman won the first set, 6-0, and he led 4-2 in the fifth. Patty came back for a 11-9 victory in the decider. The semi-final, against another American, Bill Talbert, was even closer. The contest was frequently stopped due to thunder, usually when Talbert had the momentum. Patty pulled that one out too, 13-11 in the fifth.

Waiting in the final was, of course, Jaroslav Drobný. Budge won the first two sets, then conceded the third and fourth. The pair were playing their fourth match at a major in four years, and every time, it went five sets. The few weeks of moderate training paid off. Drobný wrote, “I doubt whether, since that day, he has reached such a peak of physical fitness.” Patty won the fifth set, 7-5, and claimed his first major victory.

A few weeks later, Wimbledon tested his fitness even further. Once again on the other side of the draw from Drobný, he coasted through the singles, relatively speaking. He won a pair of four-setters to beat Talbert in the quarter-finals and American up-and-comer Vic Seixas in the semis. Drobný lost in the semi-finals to the top seed, Australian star Frank Sedgman.

Sedgman needed five sets to get past Drobný, and he had used another five to beat Art Larsen in the quarters. Both finalists could’ve used a day off, but the scheduling committee had another idea. The two men got a preview of each others’ games in a men’s doubles quarter-final, Patty pairing Tony Trabert and Sedgman with Ken McGregor. On a different day, it might have served as a light warm-up. Instead, the match took nearly six hours, with a second set that ran to 31-29. At Wimbledon, balls were only replaced for each new set, and midway through the marathon frame, Trabert had to threaten to hit the dead balls out of the stadium just to switch back to the lightly-used balls from the first set.

The Americans won the doubles, but Trabert didn’t have much hope for Patty the following day. Sedgman was the typical, hyper-fit Australian, while Budge… well, Budgie had been off tobacco for seven whole weeks!

Patty’s fitness didn’t let him down, but it was his tennis mind that won him the Wimbledon crown. Hopman wrote that “no other player in world tennis puts as much thought into the game,” and the American went into the final with a plan. While the two men had never played a singles match against each other, Patty had seen plenty of the Australian, both in singles and in the previous day’s interminable doubles struggle.

Sedgman didn’t like to face a net-rusher, so Patty came in behind every serve. Sedgman didn’t usually come in behind his own serve, preferring to attack a weak service return and come in behind that. So Patty sliced his returns as deep as possible. Sedgman tended to crowd the net, so Patty lobbed at every opportunity–including three times on match point. The Parisian from Arkansas triumphed, 6-1, 8-10, 6-2, 6-3.

* * *

Patty is still one of just three Americans to win the “Channel Slam,” the Roland Garros/Wimbledon double. Don Budge did it in his Grand Slam year of 1938, and Trabert accomplished the feat in 1955.

Both Trabert and Don Budge finished their historic summers with a title at Forest Hills. Patty didn’t even make it on court. He hurt his ankle at a warm-up event in Newport and withdrew from the national championships. The injury also derailed his hopes of playing in the 1950 Davis Cup Challenge Round against Australia. The defending-champion Americans could’ve used him. Both Ted Schroeder and Tom Brown lost to Sedgman, and the trophy went back Down Under, where it would stay until 1954.

Patty continued to tour the European circuit, but he wouldn’t again be fully fit until 1953. His reward: a Wimbledon draw in Drobný’s quarter. The last time they had played, at the Italian in 1952, the Czech exile won in a rout, 6-1, 6-0, 7-5.

Their third-round meeting at Wimbledon would push both men to their limits. It lasted almost four and a half hours, and its 93 games set a record that would stand until 1969. Patty reached match point six times, three each in the fourth and fifth sets. At 10-all in the decider, in the fading light, the tournament referee announced that only two more games would be played before the match was postponed. Drobný mustered one last bit of energy to push himself across the line, 8-6, 16-18, 3-6, 8-6, 12-10.

It was a tough match.

The crowd rose to their feet and gave the warriors a five-minute ovation. Despite cramps that attacked each player seemingly in turn, the play was of high quality throughout. Drobný wrote, “Patty and I kept our touch and accuracy to the last shot.” The American won 304 points to his opponent’s 301.

A match like that hardly needs a postscript, but it has one anyway. Patty and Drobný were doubles partners, and they came back the next day to play their second-round match. They won in four, even though neither had the energy even to pick up stray balls. Drobný had torn an abductor muscle in the singles match, and Patty–presumably without much argument–agreed to default in the doubles before sleep-walking through another round. Drobný, remarkably, reached the semis in the singles tournament. He believed that, had they not physically destroyed each other in the third round, he or Patty would’ve won the tournament.

The Czech exile would win his long-awaited Wimbledon title the following year, beating Patty in the semi-finals. Budge would never again get closer than that to a major title, losing to Trabert in the semis both at the French in 1954 and Wimbledon in 1955. He remained one of Europe’s elite, winning 14 titles in 1954, including the Italian and German championships.

In 1953, an Egyptian artist drew Patty, one side in tennis gear, the other in evening dress. One hand held a racket, the other a cigarette. A career like his would have been impossible in the States, where the game belonged to t-shirt-clad strivers in the Jack Kramer mold. Patty was the strangest of juxtapositions, an elegant Parisian from Arkansas, a dilettante willing to fight for hours on the tennis court. Of all the men who have managed both a French and Wimbledon title in the same year, no one else so adroitly kept their feet in two different worlds.