In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

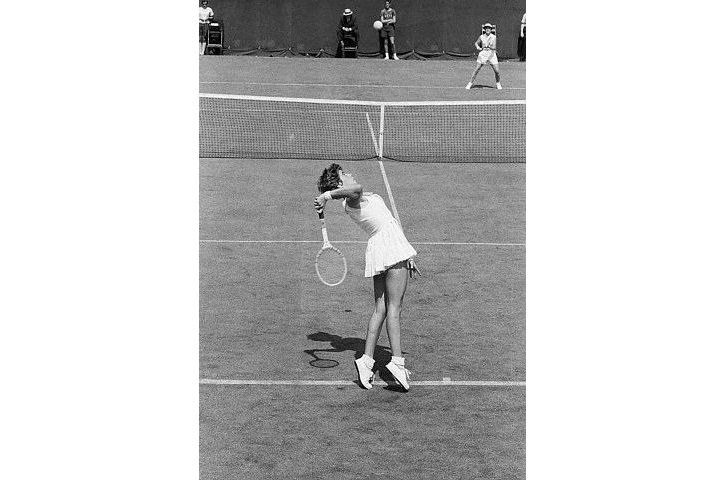

Maria Esther Bueno [BRA]Born: 11 October 1939

Died: 8 June 2018

Career: 1957-77

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1959)

Peak Elo rating: 2,184 (1st place, 1959)

Major singles titles: 7

Total singles titles: 63

* * *

In her later years, Maria Esther Bueno loved Roger Federer. Of course she did. The vocabulary that commentators resurrected to describe the Swiss star–balletic, graceful, effortless–had been employed decades earlier for Bueno. Long before Federer first picked up a racket, the lithe Brazilian was the very definition of elegance on the tennis court.

Virginia Wade faced Bueno four times in the late 1960s. She lost all four, and it’s possible that Virginia was just starstruck:

She had presence. She had that fantastic body and feline grace on the court and you were left with a fabulous memory. Her tennis presence really came from her heart. It’s like when Nureyev stands on the stage. You can’t take your eyes off him. It’s physical but it’s the soul out there as well.

Another famous Brit who fell for the Bueno allure was dress designer Ted Tinling. Tinling cut his tennis teeth in the 1920s as a personal umpire for Suzanne Lenglen, and he parlayed his insider status into a player-liaison gig at Wimbledon. He became the go-to guy for distinctive female tennis attire, and he even designed a wedding dress for 1934 and 1937 Wimbledon champion Dorothy Round.

By the time Bueno came along, Tinling was cast out of Wimbledon, the result of the controversial lace underwear he dreamed up for American glamour girl Gussie Moran in 1949. He remained as in-demand as ever. Women on the circuit knew they had made it when they wore an original Tinling. For years, one of the few champions he didn’t dress was Angela Mortimer. She preferred to wear shorts on court, and the designer eventually gave in and made her a specially tailored pair.

For much of the 1960s, Maria Esther was a one-woman runway show for Tinling. He didn’t just make dresses for her–he often made her a new dress for every match she played. She claimed that she once wore 21 of his creations in the course of a single tournament. At home, she had a closet filled with hundreds of them. The designer considered her to be a worthy successor to the great Suzanne.

* * *

Bueno’s on-court performance also–occasionally–reminded fans of Lenglen. At age 19, she swept to her first major title at Wimbledon in 1959. She defeated her friend and doubles partner Darlene Hard, 6-4, 6-3, in only 43 minutes.

Half a decade and one near-retirement later, she claimed her sixth major singles title at Forest Hills, a 6-1, 6-0 bludgeoning of Carole Graebner in 1964. She won the last 16 points in a row. No one had sealed the US national title in such lopsided fashion since Molla Mallory in 1916. Another two years on, she was nearly as good against Nancy Richey, winning her final Forest Hills trophy in 1966 after running off 10 of the last 11 games in a 6-3, 6-1 victory.

Bueno won a lot of matches–641 of them, by my best count–but when a good player stood on the other side of the net, things could get complicated. In the 1960 Wimbledon semi-finals, she faced Christine Truman, the tall, hard-hitting British hope. Bueno won the first set, 6-0, in nine minutes. (Nine!) She broke early in the second, then suddenly her serve couldn’t find the court. Truman took the second set, as Sports Illustrated put it, “aided by some thoughtless shots by Maria and some plain bad ones.”

Bueno’s poor form continued into the third set, when Truman broke her in the first game and built a 40-0 lead in the second. Somehow, the Brazilian woke up, fought back to nab the second game, and ran out the set for a 6-0, 5-7, 6-1 victory.

Angela Mortimer, the other great British player of the era, knew first-hand just how unpredictable Bueno could be:

Maria is a strange player. She is temperamental in the extreme. One day she is brilliant. The next, she is brilliantly inaccurate. One day she is smiling and chattering to everyone, the next she is silent, and passes her friends without a word.

Mortimer lost to Bueno in the 1960 Wimbledon quarter-finals, 6-1, 6-1, and she wasn’t even playing badly. Three weeks later, she held a match point against the Brazilian in Hamburg. Mortimer hit a passing shot that would’ve finished the match against anyone else. Not the Brazilian, who replied with a “perfect forehand cross-court drop-shot. If I had been wearing wings I could have landed nowhere near that ball.” Bueno came back to win, 5-7, 9-7, 6-3.

* * *

Bueno’s colleagues on the circuit called her Maria, but to her legions of fans back home in Brazil, she was Maria Esther, Esther, or the diminutive Estherzinha. She took an unusual route to the top, one that starts to explain her highs and lows. She told an interviewer in the 1980s,

To me tennis was more of an art than a sport. I was a very natural player. Everything was done by impulse or intuition. I could never be programmed like most of the players are today. Maybe it would have helped me if I had had some special advice. But I think I would never change.

She occasionally worked with the Australian coach Harry Hopman, but a more formal arrangement didn’t last a week. Hopman championed a steady program of hard training, while Bueno preferred the beach.

This isn’t to say that all of her skills came effortlessly, even if that’s what she claimed herself. While tennis was not popular in Brazil in the 1940s, her father was a recreational player with a family membership to the club across the street from their home. She treated the club as her personal playground, batting a ball against any surface she could find. When she wasn’t practicing, she’d study older players.

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

Eventually she found a book with detailed action photos of Bill Tilden’s serve. She worked for hours to replicate it perfectly, occasionally seeing results when a ball rocketed off her racket. Her gift, from the beginning, was mimicry. When world-class players visited Sao Paulo, she watched closely and tried to replicate their strokes.

Her efforts on serve, in particular, were a success. When Herbert Warren Wind assessed Bueno’s game for Sports Illustrated in 1960, he likened her movement to Lenglen’s and her serve to that of Alice Marble. Maria Esther approved of the latter comparison. Marble was the first female player to hit an offensive twist serve that equalled the deliveries of the male stars of her day.

In 1965, Los Angeles Times columnist Sid Ziff thought it would be fun to get a returner’s-eye look at the famous serve. Bueno said, “I hope I don’t hit you in the eye.” In Ziff’s telling:

Her serve swooped straight at me, hit the cement almost at my feet and hooked sharply to the right, leaving me feeling like the victim of the old-fashioned shell game. She did it again. Zip, wham and off it went at a 45 degree angle to right.

Bueno didn’t blind him, but if she had, he wouldn’t have fared any worse.

* * *

Even after Estherzinha took the Wimbledon and Forest Hills crowns as a 19-year-old, there were detractors. Wind’s Sports Illustrated profile acknowledges the case against:

The not-so-pro-Bueno group takes a much more conservative view. As they see it, her quick ascent to the top was made possible only by her arrival on the scene at one of those arid periods when there were no first-class women players around. A pretty strokes-maker, yes, with tremendous potential, indeed, but whom has she beaten?

Uncertain, roller-coaster wins like the one against Truman only solidified the case. Had Althea Gibson remained an amateur, or if Beverly Baker Fleitz continued to play the circuit, there might have been fewer laurels available for the flashy youngster to claim. When that issue of Sports Illustrated was on newsstands, a 6-4, 10-12, 6-4 loss to Hard in the Forest Hills final hardly silenced the doubters.

Just when Bueno began to show that she could pair her stylishness with steadiness, disaster struck. She began the 1961 season with only a single loss in 21 matches, winning three titles on the Caribbean swing with a trio of final-round victories over Hard. Her only loss came to Yola Ramírez in Naples, and she beat Ramírez on the way to an Italian Championships title in Turin the following week.

Before Bueno and Hard could play the doubles final to defend their Roland Garros title, Maria Esther came down with a debilitating case of hepatitis. She withdrew from the doubles and was ultimately bed-ridden for eight months. She couldn’t take her shot at a third straight Wimbledon title, and for a time, it looked like she might never play tennis again.

She was back in the spotlight soon enough–a Tinling-designed dress with pink-trimmed underwear at Wimbledon the following year made sure of that. Her game was remarkably resilient, and she won two titles in the Caribbean in March of 1962. Still, she was a shadow of her former self. She lost to a young Billie Jean Moffitt (later King) in the 1963 Wimbledon quarter-finals. “[S]he played as though she was her own ghost,” wrote David Gray of The Guardian. “[I]t seemed beyond belief that she could ever win a great singles title again.”

* * *

No one would’ve questioned Estherzinha had she chosen to retire. She had won three singles majors and another eight slam titles in doubles. She had done well financially out of the amateur game, commanding appearance fees that her fellow players could only envy. She had the adoration of an entire nation, which gave her a ticker-tape parade and put her image on a stamp after she became Wimbledon champion.

But Bueno knew that she was much closer to the top than the sportswriters gave her credit for. While she worked her way back into form, the young Australian Margaret Smith (later Court) consolidated her hold on the game. Smith won three of the four majors in 1962, and she completed her career grand slam when she claimed the Wimbledon title in 1963, still shy of her 21st birthday.

Smith was just beginning what would be a decade-plus of nearly uninterrupted domination, but she hadn’t really figured out the Brazilian ballerina. Bueno had beaten her easily just before hepatitis laid her low. The pair met four times in 1962, and while the Australian won the lot (she lost only two matches the entire season), three of the four went to a deciding set.

Years later, Bueno said that the two women brought out the best in each other. There were certainly no secrets: Between 1960 and 1968, they played 22 times, 17 of them in finals. Five of the title matches came at grand slams.

Just two months after David Gray thought Maria Esther was playing like her own ghost, she reached the Forest Hills final with the loss of just one set. Waiting for her there, of course, was Margaret Smith, who had been equally dismissive of the field. Bueno won a close first set, 7-5, then struggled in the second. She fell to 0-3, 0-40, then 1-4, 0-30. Just when Smith must have felt she was getting the match under control, the Brazilian produced what the New York Times called “one of the most electrifying bursts of super shot-making produced by a woman at the championship.” Bueno won the last five games on the trot. 18 months after picking up a racket again, she held another major trophy.

The next year, she did it again. Smith was as imperious as ever in 1964, winning her fifth straight Australian Championships along with her second French title. The defending champion arrived at Wimbledon riding a 33-match winning streak. She made it 38 by coasting through the first five rounds at the Championships.

The Forest Hills title the previous year had proven that Bueno could once again compete at the highest level. But in the amateur era, Wimbledon was a pinnacle above all others, and she had yet to climb it since her comeback. Commentators still doubted Maria Esther’s fitness–she had won the first set from Smith in the Roland Garros final, but she collapsed to a 5-7, 6-1, 6-2 loss. At Wimbledon, once again, it would be–in Bueno’s words–“three sets against the best of the world.”

If the head-to-head record is to be believed, Bueno was the weaker of the two players on court that day. And as Billie Jean King observed a couple years later, the Brazilian had a lost a step to her various injuries. But as Smith struggled under the pressure, Estherzinha showed the Centre Court crowd what had made her a champion just four years before. Gray wrote,

[I]n the crisis of the match she invariably found it possible to produce luxurious quantities of shots which were rich and imaginative, graceful and deadly. She was the more effective server; she did not miss a smash and, in the recollection of even the oldest members, no woman has hit so many beautiful and piercing volleys.

Bueno won the epic duel, 6-4, 7-9, 6-3, and when Smith lost early at Forest Hills, she tacked on a sixth major with her 25-minute dismantling of Carole Graebner.

The Brazilian had always held herself to the highest standard. She said, “I was never satisfied if I did not play beautifully. I was always going for the impossible shots.” She didn’t always manage to play the graceful tennis that she so admired in Roger Federer. And she missed more than her share of low-percentage shots, even when the smart play would’ve been a safer one.

Yet even on the biggest stages, against the best players of her era, she was capable of serving like Marble and moving like Lenglen. When everything came together, the result was everything she aimed for: impossibly beautiful.