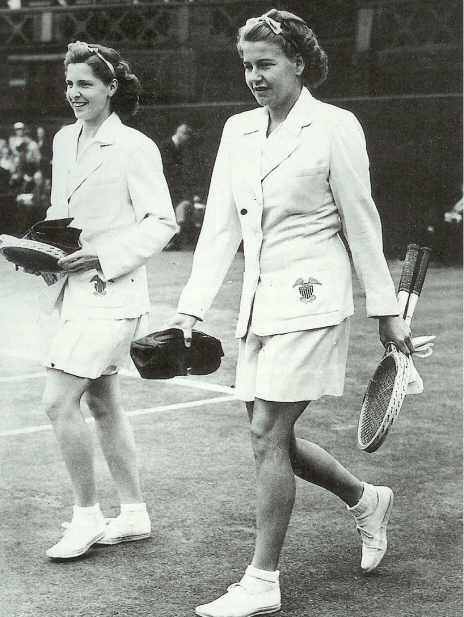

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Margaret Osborne duPont [USA]Born: 4 March 1918

Died: 24 October 2012

Career: 1935-62

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1947)

Peak Elo rating: 2,302 (1st place, 1951)

Major singles titles: 6

Total singles titles: 48

* * *

In the early 1930s, Hazel Wightman made a trip back to her old stomping grounds in San Francisco. Now established in Boston, the four-time national champion was the doyenne of American tennis. She surveyed the local talent, including a hard-hitting teenager from Oregon named Margaret Osborne.

Osborne’s mother asked what she thought. Wightman didn’t consider the youngster to be national champion material. “She’s too nice. She doesn’t have the killer instinct.” Wightman knew a thing or two about what it took to destroy an opponent on the tennis court. Back in 1910 as Hazel Hotchkiss, she had won a golden match–48 points in a row–against a poor girl in Seattle.

Wightman was a keen judge of talent, but she was wrong this time. She didn’t misjudge Osborne’s personality–the youngster really was that nice, and her main flaw as a young player was her inability to finish points. But the apparent kindness wasn’t what defined her on the tennis court. More than anything else, Margaret was calm, ignoring the annoyances that derailed other players and keeping her head when matches were tight.

In one title match after another, her unflappability was put to the test. Osborne won her first major at the 1946 French Championships, saving match points against Pauline Betz. Betz had beaten her in every previous meeting on clay and in most of their matches on other surfaces, too.

Margaret won her first US national championship in 1948 in circumstances that are almost impossible to believe. They would’ve overcome just about any other player. Two days before she was set to face the defending champion, her great friend and doubles partner Louise Brough, Osborne had learned that her father died after being hit by a car back home in California. Her mother convinced her to play anyway–that’s what Dad would’ve wanted.

The match that ensued was, by games played, the longest in the tournament’s history. Two rain delays stretched the contest even longer, further testing the players’ nerves. Osborne and Brough both possessed devastating American Twist serves–“two bombs,” as Doris Hart put it–and neither could break for the first 26 games of the third set. Some spectators lost their patience with the stalemate, chanting “Bring on the men!” Somehow, Margaret made the first move, and she won the match, 4-6, 6-4, 15-13.

Maybe she didn’t have the killer instinct, but at age 30, she had what it took to become the national champion.

* * *

Margaret Osborne duPont–she gained a last name when she married businessman and horse breeder Will duPont in 1947–is best known for her feats on the doubles court. With Brough, she won the title at Forest Hills for nine years running and 12 times overall. (She also won the women’s doubles title the year before the streak began, with Sarah Palfrey Cooke.) Altogether, Brough and Osborne duPont won 20 majors together. Margaret added another 10 mixed doubles titles with four different partners over a span of nearly two decades.

It’s easy to forget what a formidable–and versatile–singles player she was, as well. She won a second Roland Garros title in 1949, making her just the second American woman, after Helen Wills, to win the French twice. She is one of only 13 women to win two French titles as well as two (or more) other majors:

Suzanne Lenglen Helen Wills Margaret Osborne duPont Doris Hart Maureen Connolly Margaret Court Chris Evert Martina Navratilova Steffi Graf Monica Seles Justine Henin Maria Sharapova Serena Williams

If you wanted to compile a ranking of the 13 best players of all time, you could do a lot worse than to start with this list.

Osborne duPont’s career haul of six major singles titles–three at Forest Hills, two at the French, and one at Wimbledon–puts her in elite company. The strikes against her were largely out of her control: her peak was relatively short, and she excelled during a relatively weak era, when Pauline Betz had just turned pro and the European game was still recovering from World War II.

The war limited her playing opportunities when she could have been at her peak. She didn’t win her first major until 1946, when she was 28. She cut back on travel after her marriage in late 1947, and the 1950 season was the last time that she played at least 30 matches. An elite doubles player for two decades, she packed a lot of results into a much shorter span as a world-beater on the singles court.

* * *

It’s ironic that family life limited Osborne duPont’s playing opportunities, because she married one of the great tennis fans of the 20th century.

William duPont, Jr. was a scion of the Delaware duPont family, whose fortune dated back nearly a century to its origins in the gunpowder business. Will was more interested in horses, and he turned the family’s 400-acre estate, Bellevue Hall, into a center for his thoroughbred breeding and training operation.

He also converted Bellevue into a luxurious stop on the women’s tennis circuit. He built eight tennis courts–including grass, cement, and both outdoor and indoor clay. During World War II, some long-established tournaments were suspended, and duPont stepped into the breach. The estate in Wilmington, Delaware became part of the summer grass-court swing.

Pauline Betz played at Bellevue in 1944 and 1945, beating Margaret both years. She described the experience:

As many as thirty-six players at the same time have been living at [Bellevue] wondering what the poor folk were doing. We drop tennis clothes on the floor and receive them back laundered and ironed; breakfast and lunch at any hour; converge on the dinner table for home-grown steak or roast beef; raid the ice box once or twice per night for home-made ice-cream, and just can’t understand how we gain weight during an exhausting tournament.

Margaret said of Will, “He wasn’t very good, but he sure loved to play.” Perhaps it was inevitable that after he divorced his first wife in 1941, he would marry a tennis player. Alice Marble claimed that Will said he’d leave his wife for her. Louise Brough told an interviewer much later in life that he had hit on her as well. Both Brough and Betz reported that Will always smelled bad, a trait they attributed to his eccentricity but might have been because he spent so much time with his horses.

When Margaret married Will, her life changed. She would never again need to worry about money, and she developed a love of horses that would last for the remainder of her life, long after the couple divorced in 1964. But Will was set in his ways, and some of those habits got in the way of competitive tennis. She knew what she was getting into, but it must have bristled that her schedule was no longer her own.

The first thing that the world top-ranked singles player lost when she became Mrs. duPont was any kind of opportunity for post-match celebration. Will was a homebody, so after Margaret finished her last match at Forest Hills–even if it was decided by an epic 15-13 third set–they caught the 8:30 train back home to Wilmington.

More damaging to Osborne duPont’s legacy, the marriage prevented her from ever playing in Australia. Will took his annual holiday in January, and he expected Margaret to accompany him to California. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, a succession of American stars–Hart, Brough, Maureen Connolly–made victorious trips Down Under. Given the opportunity, Osborne duPont probably would’ve picked up another major and won the career slam–very possibly doing the same in doubles as well.

* * *

I mentioned that Margaret was known for her calm under pressure. That didn’t mean that her opponents had much chance to relax.

S. Wallis Merrihew, the editor of American Lawn Tennis, assessed her game in 1942:

She has all the strokes and they are men’s strokes. Maurice McLoughlin and Billy Johnston at their highest and best could scarcely surpass it. Her serve is ideal to go to the net on, her volley is on a par with it, she can smash and drive with the best of them.

Pauline Betz was particularly impressed by Margaret’s overhead smash. In her autobiography, Wings On My Tennis Shoes, she made a brief list of the players with the best smashes. It was all men–Jack Kramer, Richard “Pancho” González, and so on–except for one woman: Osborne duPont. Betz poked fun at her own shaky smash and said that unlike her, the likes of Kramer and Osborne “cannot understand why there should ever be a question of missing.”

Margaret was a few years older than Kramer, and she reached her peak at about the same time. Kramer, along with González, Ted Schroeder, and others, popularized the “Big Game”–relentless, high-percentage serve-and-volley tennis. The women’s game had always been more baseline oriented, especially as generations of Americans tried to emulate the slugging prowess of Helen Wills.

Osborne duPont and Brough didn’t quite adopt the all-out net attack that came to define the men’s game, but they displayed an all-court prowess rarely seen at women’s tournaments. It’s part of what made them so deadly as a doubles team. Betz said that Osborne duPont was “almost impossible to hit through or past in a doubles match,” even if she sometimes missed volleys in singles.

* * *

Forty times in their career, “Ozzie” and “Broughie” faced off in singles. (This was not a strong era for nicknames.) Brough won their first eight meetings, and they split the rest down the middle. 27 of their encounters were in finals, 4 of them with a grand slam title on the line.

Osborne duPont’s one triumph over Brough in a major final came in the epic 1948 match at Forest Hills. The other three didn’t quite measure up to the same standard, but the big-serving duo always made things interesting. At Wimbledon in 1949, Brough won by the oddball scoreline of 10-8, 1-6, 10-8. Margaret had four set points in the first set, and she was two points away from closing out the match on her own serve at 6-5 in the third. This is in the era before sit-down changeovers, and unlike Forest Hills, Wimbledon didn’t give players a ten-minute intermission after the second set. The two women were on their feet, without pause, for 43 games.

The 1949 Wimbledon final also stood out in memory for another reason. Cynthia Starr and Billie Jean King interviewed the two women for their 1988 book, We Have Come a Long Way. Osborne duPont’s reputation was that she never choked. She said, as humbly as she could manage, that she couldn’t remember ever choking. The two women rarely disagreed, but Brough “gently disputed” the point–surely thinking back to that marathon title match.

Margaret certainly didn’t choke very much. Her last major title came when she was 44, in mixed doubles at Wimbledon in 1962. She and Neale Fraser finally secured the trophy after 41 games, beating Ann Haydon and Dennis Ralston, 2-6, 6-3, 13-11. In another classic mixed doubles match, Ozzie and Bill Talbert beat Gussie Moran and Bob Falkenburg, 27-25, 5-7 6-1. In Margaret’s memory, “The wind was so strong … that you couldn’t possibly win a game on one side of the court.” The match was postponed at 22-22 in the first set, and sanity prevailed in the less extreme conditions of the following day.

Osborne duPont was at Wimbledon in 1962 as the coach of the US Wightman Cup team. Mixed doubles at the Championships was just a bonus. It had been three decades since Hazel Wightman herself–the original force behind the annual international meeting–had doubted Margaret’s potential. Since then, Osborne duPont had won 37 grand slam titles. She went undefeated in 19 Wightman Cup matches. She ranked among the US year-end top ten 14 times, three of them after she became a mother.

She didn’t think there were any particular secrets to her success. In 1962, she told a reporter, “I just enjoy tennis very much and play the game a lot. It’s as simple as that.” Sure, yes, that, plus a serve with so much spin that spectators could hear a swish as the racket made contact. Wightman was wrong, but no matter. “In a way it was a compliment. I considered her one of my very best friends in tennis.”