In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

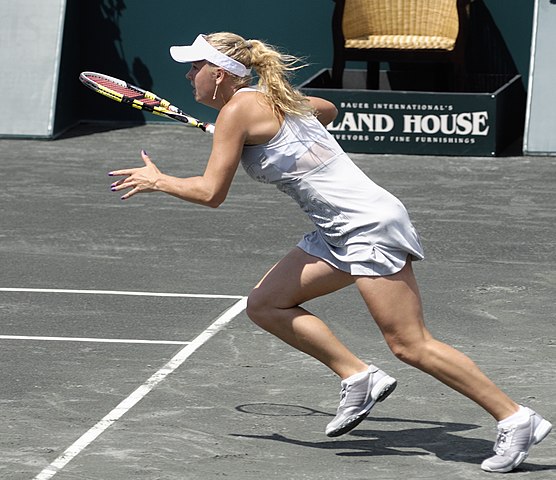

Caroline Wozniacki [DEN]Born: 11 July 1990

Career: 2006-20

Plays: Right-handed (two-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (2010)

Peak Elo rating: 2,251 (1st place, 2010)

Major singles titles: 1

Total singles titles: 30

* * *

At the 2015 Australian Open, Caroline Wozniacki told a reporter at the Australian Open, “It’s not a sprint, it’s a marathon.” It was a healthy attitude for her to have: She hadn’t reached the quarter-finals in Melbourne for three years, and her place in the top ten was precarious. She also knew what she was talking about. Two months earlier, she had completed the New York City Marathon in three hours and 26 minutes.

Obvious as it is, the marathon serves as a metaphor for Wozniacki’s career at every scale. In a single match, she could outrun anyone–even for 2 hours and 49 minutes against a fellow warrior like Simona Halep, as in the 2018 Australian Open final. She played a busy schedule when her body allowed it, topping 80 matches per year from 2009 to 2011, and playing 82 again in 2017.

It’s at the full-career level that Caro’s persistence truly comes into focus. Her failure to convert match points in the semi-finals of the 2011 Australian Open hung heavy over her reputation for years, and she felt it as much as anyone. She entered 27 more majors before she finally shook off the “slamless” tag. In between, she suffered 16 first-week exits and fell to players outside the top ten 23 times.

No one would’ve blamed her for an early retirement. She struggled with injuries in 2015 and 2016, and she was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis before the 2018 US Open. Plenty of WTA greats have called it quits in their late 20s or earlier, and Caro’s early-career exploits had made her a fan favorite and a decamillionare many times over.

Yet when she put the injuries behind her in late 2016, she started to look like the Wozniacki of old. Rebuilding a ranking that had fallen as low as #74, she picked up titles in Tokyo (over 18-year-old wild card Naomi Osaka) and Hong Kong to finish the 2016 season in the top 20. In 2017, she reached eight finals, defending her Tokyo title and beating Venus Williams for her first year-end championship.

When she finally won her first major the following year, it was a triumph of perseverance fitting for a distance runner.

* * *

In a roundabout way, my entire Tennis 128 project started with Caroline Wozniacki. Her career encapsulates the difficulty of comparing different types of achievements, and I’ve spent countless hours in the last few years trying to crack the code of how to do so.

I ran a Twitter poll back in January of 2020, when Wozniacki announced her imminent retirement. The question: Where did Caro rank among women in the Open Era? Voters were all over the place, with some weighing heavily her 71 weeks at number one, while others considered her to be outside the greatest-of-all-time conversation entirely. My first stab at a GOAT metric, the Greatness Quotient, ranked her 19th among women since 1977. As I’ve improved my methodology, she’s lost a few places, but she still merits a position on the list ahead of many multi-slam winners.

Only nine women in the Open Era have occupied the top spot for longer. She reached the number one ranking in 2010 at age 20, and despite a short spell in second place in early 2011, she finished 2011 as number one as well. She turned in a respectable performance with the coveted ranking, going 73-23 with five titles and a near-miss at the 2010 year-end WTA Championships.

But the most important number in most greatest-of-all-time debates remains the grand slam count. For most of her career, Wozniacki was stuck at zero. In five grand slams as the top seed, she got close only once, when she came within a single point of defeating Li Na in the 2011 Australian Open semi-finals. She limped out of the US Open semis against Serena Williams the same year. The rest of her span at number one at majors consisted of one exit apiece in the quarter-finals, fourth round, and third round. It wasn’t bad, exactly, but with women like Serena and Kim Clijsters swatting her off the court at will, fans reasonably wondered if the ranking formula had it right.

Adding to the confusion was that Wozniacki just didn’t look like a number one. She chased, she counterpunched, she moonballed … she wore down opponents until they finally beat themselves. Even when it worked, it often wasn’t particularly eye-catching. And when it didn’t work, you wondered how she ever won at all.

Whatever the optics, Caro’s defensive game got the job done. She could certainly keep up with anyone. Even against Serena Williams, who beat her in 10 of 11 meetings, she forced a third set five times. In 2010 and 2011, she won just short of 80% of her matches, including 16 of 24 against the top ten.

It just didn’t work at slams.

* * *

When Wozniacki rose to number one, fans had gotten plenty of practice adjusting to the idea of a slamless number one. Jelena Janković held the position for 18 weeks in 2008-09, and Dinara Safina claimed it for half of 2009. Both women were plausible contenders when they ascended to the throne. Janković had reached two slam semis, and she made the final at her first major after attaining (and quickly losing) the number one ranking. Safina was coming off the 2009 Australian Open final, and she was runner-up again as the top seed at the French.

Janković and Safina also looked like number ones, at least at their best. Janković sported a flashy, aggressive baseline game. The six-foot-one-inch Safina had the power to hit opponents off the court. Neither player ever picked up a major, but both unquestionably had the weapons to do so.

Caro was different. She had reached the 2009 US Open final, where she lost to Clijsters, but by the time she grabbed the top spot from Serena, her last four slam showings consisted of a semi-final, a quarter-final, and two fourth-round exits. She departed Wimbledon after a 6-2, 6-0 drubbing at the hands of Petra Kvitová, and only one of her vanquishers–#8 Vera Zvonareva–ranked inside the top 16.

Skepticism was understandable, especially when Wozniacki only modestly improved on her grand slam performance in her time as number one. Critics weren’t shy about picking apart her game style. When she retook the top spot in February 2011 with a decisive 6-1, 6-3 victory over Svetlana Kuznetsova in Dubai, Caro was ready with an answer:

[W]ell, if I don’t have a weapon, then what do the others have? Since I’m No. 1, I must do something right. I think they’re not actually criticizing me. I think the other players should be offended.

It’s true that many people weren’t attacking Wozniacki herself–though plenty did. The ranking system itself was a frequent target. It rewarded players who slogged it out week after week, winning small tournaments and turning in respectable results at majors. A different system, one that gave greater weight to slam performances, would’ve kept Serena at the top, despite her limited schedule.

Still, Caro’s achievement was more than a statistical quirk. According to my Elo ratings–a very different algorithm from the one that powers the WTA computer–she reached the top of the table at the end of 2009. Elo credits her with 35 weeks at number one–fewer than the official count, but still a tally that indicates she was no fluke. She was never the most feared player in the game, but she was probably the best on tour for about two-thirds of a season.

* * *

For her entire career, Wozniacki got the same unsolicited advice from commentators, journalists, and fans. She was so passive; couldn’t she attack more? Even a little bit?

She took defensive tennis to a new level. The Match Charting Project has logged every shot of more than one hundred of her matches. By Rally Aggression Score–a metric that quantifies how frequently a player ends points, either for good or bad–Wozniacki ranks among top four most passive players in the dataset:

Player RallyAgg Sara Sorribes Tormo -135 Sara Errani -96 Arantxa Sanchez Vicario -92 Caroline Wozniacki -88 Monica Niculescu -86 Agnieszka Radwanska -86 Gabriela Sabatini -83 Chris Evert -78 Alize Cornet -76 Yulia Putintseva -75

The three players who score as more passive than Caro are clay-court specialists, while Wozniacki was more comfortable on hard courts. It’s a game style that is rapidly dying. The most passive player among more recent standouts is Elina Svitolina, who rates at -49, while Simona Halep’s career average is -34. Halep is closer to the average rating of zero than she is to Wozniacki’s level of passivity.

Despite the conventional wisdom, Wozniacki’s defensiveness was a feature, not a bug. When she finally won her first major, a three-hour slugfest at the 2018 Australian Open, she hit 24 winners and 24 unforced errors to Halep’s 38 and 45. Aggression score: -109. In the final of the 2017 year-end championships, she hit 19 winners and 7 unforced errors to Venus Williams’s 31 and 39. Aggression score: -160.

Sometimes, Wozniacki’s unwillingness to change things up bordered on trolling. She was known for hitting her first serves in a specific pattern: wide on the first point of the game, down the middle on the next two, and wide on the fourth point. She followed that sequence more than 80% of the time, and in some matches, she never deviated from it at all.

Such predictability sounds like a recipe for disaster. Had she come along a decade later, facing hyper-aggressive returners like Jelena Ostapenko and Aryna Sabalenka, it might have been her downfall. (Ostapenko beat her all four times they played.) Most of the time, though, it didn’t seem to matter any more than her indifferent forehand. At 4-all in the third set of the 2018 Aussie final, she stuck with the plan, going wide-middle-middle-wide against Halep. The two serves down the middle weren’t even that close to the line. Even after double-faulting at 40-15, she got her hold.

* * *

When the 2018 season began, three years after she ran the New York City marathon, Wozniacki still appeared to be treating the majors like a distance race of their own. She had reached the second week of only two of her previous eleven slam entries, and she lost easily to Angelique Kerber in her one appearance in a semi-final.

Serena Williams missed the 2018 Australian Open due to injury, leaving the draw wide open. Sportsbooks set the odds with a whopping six co-favorites: Wozniacki, Halep, Kerber, Svitolina, Karolína Plíšková, and Garbiñe Muguruza.

Caro was the second seed, but the pressure was off. When she faced two match points against 119th-ranked Jana Fett in the second round, she escaped the sort of trap that had bedeviled her so often at slams. The draw opened up, and she reached the final without facing an opponent ranked in the top 20. The championship was decided in a hot, humid battle of attrition against Halep, a defender every bit as determined as she was. Caro was predictable, passive, and just a little bit better. She took the title, 7-6(2), 3-6, 6-4.

Exactly six years after she lost the number one ranking to Victoria Azarenka in 2012, she got it back. No woman has ever reclaimed the top spot after such a long span. This time, there were no questions about whether she deserved it. For the slam-winning, top-ranked Caroline Wozniacki, it had always been a marathon–one in which she got to decide when she crossed the finish line.