In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Gottfried von Cramm [GER]Born: 7 July 1909

Died: 8 November 1976

Career: 1929-55

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1937)

Peak Elo rating: 2,105 (1st place, 1935)

Major singles titles: 2

Total singles titles: 75

* * *

Some sports stories never get old. For me, every single tale of the sportsmanship of Gottfried von Cramm is worth repeating.

Nowadays, if a tennis player commits the most modest act of kindness on court–say, he suggests that his opponent challenge a close call–Twitter explodes with praise and the tournament rushes to post a clip on YouTube of the historic moment. Nobel Peace Prize nominations are filed forthwith.

Gottfried Cramm–he dropped the aristocratic von as well as his title of “Baron” for most introductions–did that sort of thing every day before breakfast.

The first time Don Budge met Cramm, it was 1935, and both men had both just won their Wimbledon quarter-final matches. They were slated to meet in the semis. Cramm took the 20-year-old Budge aside, and explained that in his match against Bunny Austin, he had been “a very bad sport.” A close call went against Austin, and Budge agreed that the linesman made a mistake. To put things right, Budge tanked the next point.

That’s how Bill Tilden did things. Even though Tilden’s brand of theatrics went beyond what most players would dare, a generation of American players followed his lead. They thought it was the sportsmanlike way of responding to such unfairness. But no, Cramm explained: “You made yourself an official, which you are not, and in improperly assuming this duty so that you could correct things your way, you managed to embarrass that poor linesman in front of eighteen thousand people.”

In Cramm’s view, proper treatment of everyone–including linesman, who were often of a middling standard, at best–came first, ahead even of fairness on court.

Once, when a linesman called Cramm for a foot fault, the German apologized.

(Once, when a linesman called Jim Courier for a foot fault, the American said, “F— you.”)

In the 1935 Davis Cup Interzone Final, Cramm played what one of his opponents, the American Wilmer Allison, called “the greatest one-man doubles match.” Daniel Prenn, until recently Cramm’s equal, had been barred from the German national team due to Nazi racial policies. (Prenn was Jewish.) Instead, doubles duty with the Baron fell to the much weaker Kai Lund.

Gottfried’s play that day was so dazzling that the German team came within a point of victory. After Lund missed an easy volley on the fifth match point, he hit a winner to earn a sixth. But Cramm told the umpire what no one else in the stadium had noticed–the ball grazed his racket before Lund made his shot. The Germans conceded the point. They lost the match and, with it, any hope of winning the tie.

The Davis Cup meant a great deal to the Nazis. A federation official traveling with the team criticized the star player, accusing him of failing the German people. Cramm responded:

Tennis is a gentleman’s game, and that’s the way I’ve played it ever since I picked up my first racket. Do you think that I would sleep tonight knowing that the ball had touched my racket without my saying so? Never, because I would be violating every principle I think this game stands for. On the contrary, I don’t think I’m letting the German people down. I think I’m doing them credit.

* * *

Cramm’s personality and aristocratic bearing were so compelling that, even eight decades later, it’s easy to forget that he was one hell of a tennis player.

The German packed a lot of tennis into a very short span of time. Unfortunately, his time at the top overlapped that of Don Budge and Fred Perry. Budge once said, “Gottfried was the unluckiest good player I’ve ever known.”

Cramm won his first title in Germany in 1929, just after his 20th birthday. He made his major debut at Roland Garros and Wimbedon in 1931, and played his first Davis Cup rubbers in 1932. By 1937, he was on sufficiently thin ice with the Nazis that the German federation didn’t enter him in singles at the French, where he was the defending champion. The following March, he was jailed for a homosexual affair.

In little more than half a decade, the Baron won the French Championships twice, beating Jack Crawford in 1934 and Perry in 1936. He played 14 majors in total before World War II, and reached the final in 7 of them. Every loss was at the hands of Perry or Budge, and he was injured in a taxi accident on the way to one of the clashes with Perry. He tacked on another three major doubles championships, not to mention a whopping 65 match wins for Germany’s Davis Cup team.

After his arrest and imprisonment 1938, Cramm’s career was effectively over. Wimbledon wouldn’t grant a place in its 1939 draw to a man convicted of morals charges, and the black mark on his record prevented him from getting a US visa. The character of his Nazi accusers counted for nothing.

Yet the German clearly had more championship-quality tennis in his racket. At Queen’s Club in 1939, he beat the strong American player Elwood Cooke in the quarter-finals. In the semis, as sportswriter Al Laney put it, “He simply smothered Bobby Riggs,” winning the first 11 games in a row. Cramm had to sit out Wimbledon, and a few weeks later Riggs beat Cooke for the title there.

Gottfried wasn’t allowed to return to Wimbledon until 1951, when he was 41 years old. He was no longer a factor on the world tennis stage, but his post-war performance suggests just what he might have accomplished had the Nazis never come to power. Between 1946 and 1954, playing mostly in Germany, he tacked on 27 titles to his career record. Unlucky, indeed.

* * *

Cramm’s best shot was, very possibly, his American Twist-style second serve. Marshall Jon Fisher’s excellent book, A Terrible Splendor, centers on the great 1937 Davis Cup match between Budge and Cramm. Fisher describes the kicker:

Von Cramm has a famous second serve, maybe even better than his first. He likes to toss the ball a bit to his left, almost behind him, and arch his back as he swings to create a rounded motion, catching the ball from left to right as well as back to forward, creating enormous topspin. … On clay it has a particularly ferocious high bounce, since spin has more effect on clay, but even on the grass he is able to win points outright with his second serve.

The second serve was particularly deadly in one of Cramm’s most memorable matches. In the 1936 Davis Cup Interzone Final–the round that determined which nation would take on the defending champion for the trophy–Cramm edged out the Australian Adrian Quist by the narrowest of margins, 4-6, 6-4, 4-6, 6-4, 11-9. The German saved five match points, and he needed nine of his own. It was a gusty day, and it was a wind-aided Cramm kicker that finally settled the contest.

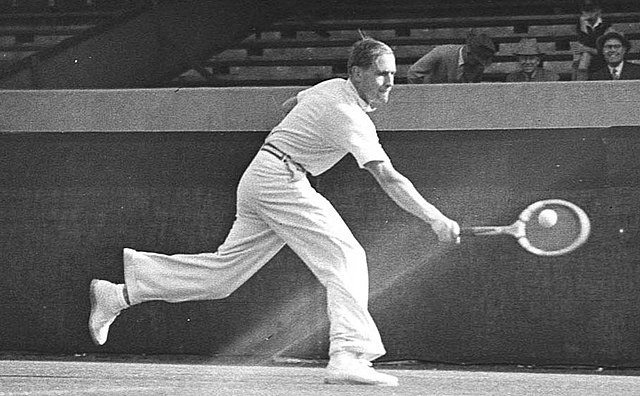

The Cramm service motion

Cramm’s serve wasn’t the only American influence in his game. Bill Tilden first visited the von Cramm estate in 1928, and he spent a great deal of time with the young player. He particularly focused on Gottfried’s backhand, replacing a defensive slice with a topspin stroke like his own. Tilden would remain in Cramm’s corner throughout his career, even coaching the German Davis Cup team when they took on the Americans in 1937.

Few men could teach tennis like Tilden could. Al Laney wrote of the Baron’s new-and-improved shot, “[F]ew players ever had a stroke to compare with his ‘flat’ backhand, with which he occasionally blinds the gallery.” Harry Hopman said, “Gottfried was the most fluent and best looking stroke maker I have seen in my fifty years of international tennis.”

* * *

While I’m reeling off the superlatives, how about this one from British Davis Cupper John Olliff: “He could raise his game a little above what you and I always thought was perfect. For short spasms he could make Budge look like a qualifier.”

One of those bursts of brilliance was particularly well-timed. Budge and Cramm faced off in what was long considered to be the greatest match of all time. In 1937, Germany and the United States met in the Davis Cup Interzone Final. The winner would advance to the Challenge Round against Great Britain to decide the winner of the Cup. Both Germany and the US would be favored against the Brits, so the Interzone tie was effectively the final. Budge and Cramm met in the decisive fifth rubber.

Just a few weeks earlier, the American had trounced the Baron in the Wimbledon final, 6-3, 6-4, 6-2. Budge was fast becoming the best player in the world: He would win six majors in succession, including all four in 1938. Cramm was gracious (as usual) in defeat: “‘I was quite satisfied with my form today. But what can one do against such perfect tennis?”

One way to beat Budge was to partner with Helen Wills Moody (left)

Cramm must have been even more satisfied with his form in the Davis Cup match. He won two close sets, 8-6 and 7-5, to take a commanding lead over the Wimbledon champion. The level remained astonishingly high, and after Budge took the third set, Tilden told a reporter it was the greatest Davis Cup match he had ever seen.

Budge grabbed an early lead in the fourth, and Cramm let the set go to save energy for the fifth. The German raced out to 4-1 in the decider, and Budge held on only by adopting the risky strategy of taking Cramm’s high-bouncing second serves on the rise. The American drew even, and with a burst of spectacular shotmaking, Budge sealed the match, 8-6 in the fifth.

For the remainder of his life, US Davis Cup captain Walter Pate told anyone who would listen that it was the greatest match ever played.

* * *

In the tennis world of the 1930s, the stakes didn’t get any higher than the Davis Cup. The Americans, as expected, swept aside the British defenders and reclaimed the Cup for the first time since 1926. The Nazis were well aware of the trophy’s status, and Cramm’s inability to secure the Davis Cup for Germany contributed to his downfall.

Tilden suggested that Gottfried take a break after the Davis Cup, but the Baron kept playing. He headed to the United States, where he won the US national doubles title but lost to Budge in a five-set final at Forest Hills. He kept moving west, playing at the Pacific Southwest in Los Angeles before sailing–with Budge–to Australia.

Budge and Cramm (right) after the 1937 US final

He told Tilden that he was playing for his life. He knew that the Gestapo had enough evidence to arrest him. A few powerful tennis fans and admirers, such as Hermann Göring, couldn’t protect him forever. Perhaps a US national title would’ve made the difference, but he seemed to sabotage his own efforts. He increasingly spoke out against the regime, at one point calling Hitler a “housepainter,” and his tennis suffered from the strain. He beat Budge in a couple of exhibitions, but in the semi-finals at the Australian Championships, he lost to the 19-year-old John Bromwich.

You already know how the Baron’s time at the top ended. He went home, heard the Gestapo knock on the door, and spent several months in jail. When he returned to the tennis circuit, he was often unwelcome. When the war began, his morals conviction overrode his aristocratic status, so he fought as a conscript on the Eastern front. He was eventually discharged from the military, possibly because of suspicions he was working to undermine the regime.

Somehow, he came through the conflict sufficiently unscathed that he inspired the same kind of awe in a new generation of post-war tennis players. 1951 Wimbledon champion Dick Savitt played Cramm in Egypt, and said, “He dressed so well that I hated to walk out on the court with him.”

Don Budge spent much of his own long life singing the Baron’s praises. At the 1937 Wimbledon ball, the newly-minted champion said:

I do appreciate this chance you give me to pay a tribute to a great-hearted gentleman. For when it comes my turn to lose, I hope I may lose with half the gallantry, half the graciousness, and with something of the fine spirit of sportsmanship shown by Baron Gottfried von Cramm.

Budge would say the same for another six decades. I told you: Some stories never get old.