In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

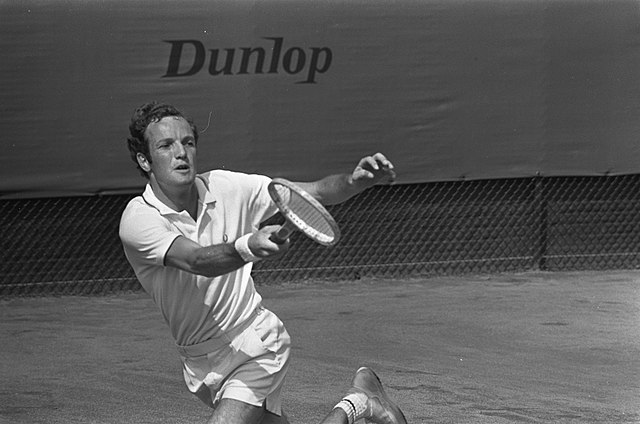

Tom Okker [NED]Born: 22 Februrary 1944

Career: 1962-81

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 3 (1974)

Peak Elo rating: 2,190 (1st place, 1974)

Major singles titles: 0

Total singles titles: 40

* * *

For a man who never won a major singles title, Tom Okker was amply rewarded for his tennis career. When the world’s major tennis federations agreed to try “open” tennis in 1968 and allow competition between amateurs and professionals, Okker became the world’s first “registered player,” a hybrid category that allowed him to earn prize money but still–unlike professionals–compete for his country’s Davis Cup team.

He was lucky that the Dutch federation was so swift to give him the new designation. At the US Open in 1968, he beat pros Richard “Pancho” González and Ken Rosewall to reach his sole major final. His opponent in the final was the still-amateur Arthur Ashe, so even though Okker lost the match, the $14,000 winner’s check was his.

At the beginning of the following year, promoter Lamar Hunt convinced Okker to join his burgeoning World Championship Tennis (WCT) circuit. Experts rated him no higher than third-best in the world, and some listed him as low as fifth. But Hunt was confident enough in his value to the tour that he offered more than $200,000 over four years.

$50,000 per year was a big payday for a recently converted amateur. But it seemed was chump change just a few years later. When the newly-formed World Team Tennis (WTT) organization drafted squads at the end of 1973, Okker was the first choice of the Toronto/Buffalo Royals, who wanted the veteran to do double duty as a player-coach. He said, “If they offer me enough money, I’ll play.” They did, and he did, on a five-year contract for a reported $136,000 per year.

Barely a half-decade into the Open Era, a select few players were already getting rich. Debates more familiar to fans of team sports took over the tennis headlines–were these men and women worth all the money? A rival WTT owner, Boston’s Ray Ciccolo, griped:

[F]rom what I’ve seen of the owners’ mistakes, I see why 80% of them are in trouble. Most made their first mistakes at the draft, before the first set of tennis. They came unprepared or didn’t have enough money to do it right. But Okker’s signing was the worst thing Toronto/Buffalo could’ve done to the league.

One reading of Ciccolo’s complaint is that elite-level money was getting handed out to players that didn’t deserve it. Okker didn’t seem like a top-tier talent next to names like Billie Jean King, Jimmy Connors, and John Newcombe. The Dutchman ranked as low as tenth on one journalist’s year-end list for 1973, and he didn’t have any unusual level of celebrity to make up for it.

Royals owner John Bassett may have misjudged Toronto’s interest in team tennis–his club folded after just one last-place finish. But he was more right than wrong in picking–and paying–Tom Okker. In addition to Okker’s doubles prowess, which was particularly valuable in the WTT format, he was a better player than either the public or the rankings gave him credit for. He was at his peak in 1973 and 1974, a frequent runner-up in a field full of all-time greats. Okker was one of the first tennis players to earn $1 million on court, and he deserved every penny.

* * *

No sketch of Tom Okker is complete without a reference to his nickname, “The Flying Dutchman.” Forgive my ignorance: I always assumed people called him that just because it was the only term they knew with “Dutch” in it, and he wasn’t noticeably slow. In fact, the man from Amsterdam was as fast as it gets.

He needed to be. A generous measurement put him at five-foot-ten-inches tall, and after his retirement, Okker said he “should have been just a bit bigger and stronger and had a dominant service.” Had those wishes been granted, no one could have stopped him.

Credit: Eric Koch

At Queen’s Club in 1968, Okker was the first amateur to beat Rod Laver since Laver turned pro six years before. The New York Times wrote that the “lean, wiry, and fantastically fast” underdog “outmaneuvered and outran the little Australian redhead.” When the Times previewed the Forest Hills final later that year, it reported, “His contemporaries insist that he is the quickest man in the history of tennis.”

This isn’t to say that Okker relied only on speedy retrieving. He was one of the first players to hit a heavy topspin forehand, and in an era when so much spin was still a novelty, it took some getting used to. The 1968 Times preview warned:

More than once today, Arthur [Ashe] will be tempted into letting Tom’s wicked top-spin drive go by, convinced the ball will land well beyond the base line. It will take a sharp eye, indeed, to discern balls from those sharply dipping inbounds. And when at net Ashe’s best defense may well be to reach for every ball originating from Okker’s forehand side.

The Dutchman’s combination of weapons was almost enough to win the first-ever professional major played at Forest Hills. He pushed Arthur Ashe to five sets, including a 26-game first set. The American needed one of the best serving performances of his career to come through. At 5-5 in the first set, Okker was already exasperated by his inability to get into points. After Ashe hit two more aces, Okker faced the wrong way to return Arthur’s next delivery, earning a laugh from the crowd as he signaled his surrender.

Okker quickly resumed the fight. Ashe’s game plan involved wearing out his opponent, a strategy that proved to be built on wishful thinking. The Dutchman didn’t noticeably tire, but Arthur’s serve was just enough to make the difference. The final score was 14-12, 5-7, 6-3, 3-6, 6-3, a near-miss in Okker’s one shot at a major title.

* * *

As we’ve seen, Okker had plenty of reason to be pleased with his performance in 1968. He earned over $20,000 in prize money in his campaign as a “registered player,” and his results garnered the big contract with Lamar Hunt in 1969.

What wasn’t clear at the time was just how close the Flying Dutchman came to the top of the rankings. Before 1973, rankings were unofficial, generally published by veteran sportswriters only once per year. The phenomenon of a slam-less number one is very modern, because it wasn’t possible without computer rankings. The men who used to make the lists believed that Wimbledon and Forest Hills were the only two tournaments that mattered.

Okker (left) with Ashe, after the 1968 Forest Hills final

According to weekly Elo ratings I’ve assembled, Okker was the second-best player in the world for about four months between June and September of 1969. His status was built in part on the runner-up showing at the US Open, combined with a 78-24 record–including eight titles–in the year that followed. When he wasn’t winning, he was reaching finals. He lost title matches in 1969 to Rod Laver, Roy Emerson, and (three times!) to Tony Roche.

Laver was in the middle of his second Grand Slam season, so second place was as good as a mere mortal could hope for. My ratings report an imposing top ten that Okker nearly surmounted in June 1969:

1 Rod Laver 2 Tom Okker 3 Tony Roche 4 John Newcombe 5 Andrés Gimeno 6 Roy Emerson 7 Ken Rosewall 8 Arthur Ashe 9 Stan Smith 10 Fred Stolle

As if that weren’t enough, 1966 Wimbledon champion Manuel Santana was 15th and ageless wonder Richard González was 17th. It was a great time to be a tennis fan, and a tough time to cling to a spot at the top of the game.

* * *

The cast of characters steadily changed, but the level of competition remained sky-high. Okker somehow kept up.

In 1973, he went 91-23 and won seven more titles against the likes of Ashe, Gimeno, Newcombe, and Ilie Năstase. After finding out that the Toronto/Buffalo Royals coveted his services for World Team Tennis, he continued strong into 1974, winning another title against Năstase and defeating Tom Gorman to secure a championship at home in Rotterdam.

As in 1969, Okker’s reputation was built on these occasional titles, frequent victories over strong competition, and his ability to avoid too many poor showings. Still, no one considered him much of a threat at grand slam events, and he did little to change their opinion. He reached only one major quarter-final–at the French in 1973–between 1971 and 1975.

In traditional terms, his case for a spot near the top of the rankings was even less compelling than it had been in 1969. But returning to my Elo ratings, Okker was briefly–for just one week!–the best player in the game.

It was a spell at number one worthy of Pat Rafter. Okker comes out on top for the week of June 24, 1974, when that year’s Wimbledon Championships began. John Newcombe was number one the week before, but a bad loss handed the top spot to Okker, who didn’t play that week.

The All-England Club didn’t see anything special in Okker’s play that year. The committee seeded him seventh, and he didn’t even live up to that, losing to Alex Metreveli in the fourth round. Third seed Jimmy Connors won the Wimbledon title, which was enough to leapfrog both Okker and Newcombe. Jimbo–again, according to the Elo algorithm–would keep the number one ranking until June of 1978.

Like Rafter’s week at number one 25 years later, Okker’s brief spell at the top feels like a footnote. But the unheralded feat is much more impressive when we consider the cast of characters. There weren’t many easy matches in men’s tennis in 1974. Here is the Elo list for Okker’s sole week at number one:

1 Tom Okker 2 John Newcombe 3 Jimmy Connors 4 Ilie Năstase 5 Rod Laver 6 Stan Smith 7 Björn Borg 8 Ken Rosewall 9 Arthur Ashe 10 Alex Metreveli

For the Flying Dutchman, it was a last hurrah. He was slowing down, and his topspin didn’t bewilder opponents like it once did. He would fall to fifth on the Elo list by the end of the year, and he dropped out of the top ten before Wimbledon in 1975.

* * *

Of course, no one was optimizing tennis rating systems during Tom Okker’s career, and few fans do so even today. Okker was known as a perennial runner-up, an entertaining and talented player who didn’t have quite what it took to reach the top of the game. It didn’t help his reputation that he stuck around into the early 80s, losing ten matches to Borg, eight to Connors, and another seven to Brian Gottfried.

Like his near-contemporary Tony Roche–who did manage to win a major singles title–Okker was born at the right time to share the court with a long list of Hall of Famers, even if it didn’t help him build a strong resume of his own. Also like Roche, he proved his mettle on the doubles court, winning two majors in that discipline and amassing 78 titles, a record that would stand into the 21st century.

The men with the checkbooks knew what they were doing. Okker didn’t make as much money from tennis as he would have a decade or more later, but it would’ve been difficult to imagine World Championship Tennis or World Team Tennis without him. His era was so strong that even an also-ran could earn a spot among the 100 best players of the century.

* * *

Thanks to Kees Haasnoot for research and translation help from the Dutch.