In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Vinnie Richards [USA]Born: 20 March 1903

Died: 28 September 1959

Career: 1918-50

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1927)

Major singles titles: 0

Total singles titles: 45

* * *

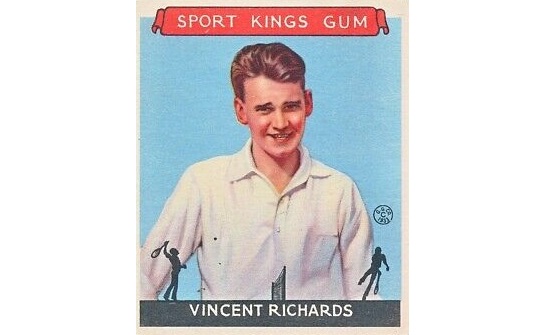

In 1933, the Goudey gum company attracted customers with a set of 48 trading cards. The cards–one with every pack–spanned 18 different sports. Every vintage baseball card collector dreams of owning the Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth issues, and other installments in the set, such as Jim Thorpe, Babe Didrikson, Red Grange, and Bobby Jones, can command thousands of dollars in good condition.

Goudey included three tennis players. First was Bill Tilden, of course, as his name was synonymous with the sport in the decades between the wars. Ellsworth Vines merited a spot as the reigning Wimbledon and US champion.

The third was Vinnie Richards. Richards’s inclusion is a bit puzzling. He turned 30 in 1933, and he had briefly retired three years earlier. He hadn’t played a major amateur tournament since 1926, as he turned pro at the end of that season. He won the US Pro championship in 1933, but it was against a weak field. Since Tilden joined the professional ranks at the end of 1930, Vinnie had been a distant number two, at best.

One explanation is that Goudey wanted three American tennis players, and after Tilden and Vines, there weren’t a lot of great candidates. Maybe the ad men in charge of the set struggled to fill out a 48-name list.* Lending credence to that theory, there’s a card for dog-sled racer Leonhard Seppala.

* Helen Wills, anyone?! There were only two women in the set.

The more likely explanation was that Richards had long been a celebrity, and his name recognition far outstripped his recent on-court accomplishments. While Vinnie never really challenged for the top spot, he was the Forrest Gump of 1920s tennis, playing a key role in the sport’s biggest stories for 15 years, especially whenever Tilden stepped aside. He was a frequent test case for the amateur rule, and he ultimately became the first male star to turn pro. He racked up dozens of tournament victories, often without losing a set. As an amateur, he toppled Big Bill more than anyone else, even if Tilden got the better of their career head-to-head.

Vinnie’s crowning achievement was a three-medal performance–two golds and a silver–at the 1924 Paris Olympics. Yet somehow, that story wasn’t even the first or second most newsworthy event of his year. After a season like that, it’s no wonder he became a celebrity.

* * *

The saga began in December of 1923. A few days before Christmas, Richards was one of four men nominated for the Olympic tennis team. Reigning Wimbledon champion Bill Johnston couldn’t go, so the foursome would be Vinnie, Bill Tilden, 1923 Wimbledon finalist Frank Hunter, and veteran doubles star Watson Washburn.

At the end of January, Vinnie got married. Wedded bliss seemed to improve his game, which had sagged in the second half of 1923. He won a title at the Brooklyn Heights Casino event in Feburary, then the newlyweds hit the road for a tennis-themed honeymoon. Richards won titles at the Jamaica International, the Florida State Championship, and the Southeastern Championship. He didn’t lose a set on the trip.

He was back at home in New York the first week of April, when he won the US Indoors with a scintillating final-round victory over Hunter. According to Tilden, Richards was “the greatest volleyer the world has ever known,” and his game agreed with indoor conditions. He retired the trophy, having now won the tournament three times.

While Richards was traveling up and down the East Coast, he found out from the newspapers that his amateur status wasn’t as secure as he thought.

Vinnie made his money from journalism, at least some of which he wrote himself. It was common practice for sports stars to lend their byline to newspapers, which used famous names to boost sales. Richards began making money this way as a teenager, when a writer named Edward Sullivan (yes, that Ed Sullivan!) penned the copy attributed to the tennis star.

Richards attended the Columbia School of Journalism in 1922, so at some point, he must have started contributing more of the prose that went out under his name. Regardless of just how much he sweated over a typewriter, Vinnie considered journalism his profession, and he needed to make money somehow.

The American Olympic Committee expected its athletes to hew to an exacting standard of amateurism. The New York Times summarized the Committee’s ruling in March:

Athletes who are members of the American Olympic team, regardless of the sport of which they are exponents, will be prohibited from writing for newspapers, magazines, periodicals or news agencies during the length of time they are under the direct jurisdiction of the American Olympic Committee.

The US Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA) had recently reviewed its own policy on amateurism and paid writing–more on that in a moment–but the Olympic Committee went even further. Vinnie had a contract to cover the Paris games for a national news agency, and there was no way to both fulfill his professional commitments and abide by the Committee’s decision.

Tilden was better known (and presumably much better paid) as a journalist than Richards. He immediately announced that he wouldn’t play the Olympics because of the policy. His decision didn’t pack the punch it might have, as he had already said in December he was unlikely to go to Paris. But the Times hinted that Vinnie might well follow his colleague’s example.

* * *

For two weeks at the end of April and the beginning of May of 1924, tennis was in the news almost every day, none of it because talented men and women were hitting balls across a net.

The USLTA had determined it would adopt a stricter interpretation of its policy on paid writing. Up to that point, the federation had accepted that its most prominent members–of whom Tilden towered over the rest–would earn money from their writing, and that the topic would often be tennis. Now it would take a harder line and consider players who made substantial sums of money that way to be professionals.

The rule wouldn’t go into effect until January 1925, but Big Bill was a prideful man–not to mention a tactician both on and off the court. On April 22, he quit the Davis Cup team, reasoning that if he did not qualify as an amateur in January of 1925, he wouldn’t in September of 1924, either.

In an astonishing coincidence*, reports emerged a week later that promoter Tex Rickard was looking at staging professional tennis events in 1925. Vinnie told the New York Times: “I know it is being thoroughly considered, not only by myself but by Tilden and a number of other top-ranking players.”

* Not a coincidence

It wasn’t the first time Vinnie clashed with the federation. Richards had been suspended by the USLTA back in 1919 for the egregious offense of working for a sporting goods manufacturer. Yes, the arrangement was basically that of endorser and endorsee, and the two sides quickly resolved their differences when Vinnie’s employer pulled advertisements that used his name to sell rackets. But it’s no wonder that Richards was willing to consider options outside the stifling purview of amateur tennis.

The day after the possibility of a pro tennis venture was leaked, Vinnie officially joined Tilden on the sidelines. He removed himself from Davis Cup consideration (possibly an empty gesture, as he hadn’t even made the team the previous year), and made it official that he’d travel to the Olympics only in his capacity as a journalist.

American tennis was in turmoil, yet at least in the New Yorker’s case, the situation was defused quickly. Richards met with a couple of USLTA officials, who assured him that he would retain his amateur status for the rest of the year, and that he’d have the opportunity to defend that status when the new rule came into effect. He was back in the Davis Cup mix, and a week later, he got out of his journalistic commitments and agreed to play in Paris.

The Olympic Committee called Vinnie’s bluff, and he fought to a draw with the tennis federation. Tilden, as always, was the bigger story, and his case would remain unresolved: He would play the US National Championships, but he skipped the Olympics, and his battles with the USLTA were far from over.

In three years, Richards would be playing professional tennis. Another four years after that, Tilden would join him. In the meantime, Vinnie had a lot of matches to win.

* * *

The bureaucratic squabbling didn’t leave Richards much time to prepare for his European trip. His first stop was Wimbledon. It was only his second appearance there. In 1923, he lost in the fourth round to Bill Johnston. Paired with Frank Hunter, who would be his partner this time around as well, he lost in the quarters to the French “musketeers” Jean Borotra and René Lacoste.

In 1924, Vinnie took a step forward in both disciplines. He reached the quarter-finals in singles before losing to Borotra (who won the title), and he and Hunter won the men’s doubles title. It was Richards’s first major final with a partner other than Tilden, and it added to his growing reputation as one of the best doubles players of the era. The only blot on his fortnight was a third-round loss in the mixed doubles with fellow American Olympian Marion Jessup.

Richards and Hunter had established themselves as the team to beat in Paris, but no one seriously considered Vinnie a threat in singles. Nor did they figure on a deep run from the Richards/Jessup duo after their early exit in London.

Vinnie didn’t offer much more hope in the first half of the Olympic week. In the second round, he needed five sets to get past the unheralded Indian, Mohammed Sleem, then went four sets against the Spaniard Manuel Alonso. The Times called it “a magnificent battle,” but it was also another long one for a player competing in three events.

The match of the tournament arrived early, in the quarter-final between Richards and Lacoste. The French “crocodile” had reached the Wimbledon final, and playing at home, he was favored to win. Richards escaped a two-sets-to-one deficit in style:

He played at times brilliantly and always surely. From 1-all, he climbed to 4-1 and then lost two games. But his reserves were unexhausted and, sometimes taking risks but never losing by it, he took first his own and then Lacoste’s service, winning as brilliant and well-fought a match as has ever been played in an Olympic championship.

Richards survived a cautious, wind-blown semi-final against the Italian player Uberto de Morpurgo, while Borotra lost to his compatriot Henri Cochet. The gold medal match went five sets, as the typically slow-starting Cochet lost the first two frames, then charged back to even the score. Despite the dramatic scoreline, the final failed to reach “any great pitch of brilliance,” and Vinnie played more conservatively than usual. Still, it was enough to outwait the Frenchman. Richards won gold, 6-4, 6-4, 5-7, 4-6, 6-2.

By the end of the Olympics, the New Yorker had learned just how formidable the French team would become. In the men’s doubles, Richards and Hunter needed five sets to get past Lacoste and Borotra in the semis and another five to seal Vinnie’s second gold medal against Cochet and Jacques Brugnon.

In the mixed, Richards and Jessup beat Borotra (with Marguerite Broquedis) in the first round and Molla Mallory (playing for Norway with Jack Nielsen) in the second. Vinnie fell one match short of the triple, losing to the superior American duo of R. Norris Williams and Hazel Wightman. Wightman was probably the strongest doubles player among the women, so if Williams, the team captain, had chosen different teams, Richards may well have taken home three gold medals.

* * *

The US team swept the five tennis events, with 18-year-old Helen Wills winning women’s singles and Wills and Wightman combining for the women’s doubles gold. But for American tennis fans, the real action was yet to come. The Olympic events were marred by the absence of Bill Tilden and Suzanne Lenglen, and they were played on clay, not the grass of Wimbledon and Forest Hills. Plus, Americans won 45 of the 112 gold medals in Paris, so there were plenty of other sporting triumphs to celebrate.

Richards skipped the traditional warm-up events before the national championships, so he didn’t play another competitive match until the national doubles championships in late August. (For most of the amateur era, the doubles tournament was held separately from the singles.) This was the event where Vinnie made his reputation: He had won the event three times, all with Tilden, between 1918 and 1922.

He failed to add another men’s doubles title when he and Frank Hunter lost in a five-set semi-final to the brothers Howard and Robert Kinsey. The Times blamed Hunter, calling Vinnie “the outstanding figure on the court.” Richards made up for it by winning the mixed title with Wills, capping their run with a three-set final against Tilden and Molla Mallory.*

* If a genie ever offers you the chance to travel back in time to the match of your choosing, it would be hard to do better than a major mixed doubles final between Mallory/Tilden and Wills/Richards.

At Forest Hills, the New Yorker’s singles game showed no rust. He reached the semi-finals with four straight-set victories, setting up a semi-final clash with Tilden. The pair hadn’t played since 1922, and even before that, Vinnie held his own, winning four of their first ten meetings. Yet Big Bill was known for rising to the occasion. The one previous Tilden-Richards meeting at the national championship, in 1920, had been all Bill, complete with a 6-0 final set.

Tilden was as prolific a writer as he was a tennis champion, so it’s no surprise to find a full description of the Richards game in one of his early books:

Richards is a player who uses spin on every shot. He has no flat shots in his game, except an occasional overhead. This is one reason why there is a lack of speed and pace to Richards’s ground game. He has even discarded top spin from his game. Every shot, except an occasional wild lift drive off his forehand–a shot I have repeatedly urged him to discard for a more normal drive–is hit with under spin. He slices his normal forehand and every backhand. He slices his volley, overhead, and service. It is only because he mixes the amount of slice with great cleverness, couples it with an uncanny sense of anticipation and unerring judgment in advancing to the net, that Richards is the great player that he is.

Hitting harder and deeper than before, Vinnie finally had a chance. He wouldn’t beat Tilden this time, either, but it was the battle that would seal his reputation in American tennis. The final score was 4-6, 6-2, 8-6, 4-6 6-4, and as Bill wrote, “Richards and I staged the match of the tournament. I never have seen Richards play so well, nor have I played better tennis this year. It was anyone’s match to the last point.” Vinnie’s defeat would look even better after Tilden straight-setted Bill Johnston in the final.

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

The US National Championships were more compelling to American tennis fans than the Olympics had been, but both paled next to the Davis Cup. The international team competition was the unquestioned pinnacle of tennis in the 1920s. The United States had held the trophy since winning it back from Australasia in 1920, and in 1924, they would face Australia (now excluding New Zealand and limited to the single country) for the fourth time in five years.

The US owed its dominance to Tilden and Johnston–Big Bill and Little Bill. The two men had played all 22 singles rubbers for the American side since the war, and won all but one of them. Tilden patched up his spat with the federation in time for the 1924 title defense, but Johnston was in decline, and he ceded his second singles spot to Richards.

Playing Davis Cup singles for the first time, Vinnie delivered. Facing Gerald Patterson and Pat O’Hara Wood, Tilden and Richards won all twelve singles sets they played. The Aussies managed only to grab a single frame from Tilden and Johnston in the doubles. Johnston would retake his singles role from Richards in 1925, but Vinnie never lost a match–singles or doubles–in Davis Cup competition.

* * *

When Richards turned professional at the end of 1926, he was as famous as ever. He won three of four matches against Tilden that year, and because Big Bill lost early at Forest Hills, the USLTA named Vinnie the top-ranked American.

His status at the top of the table would always be tenuous. Shortly after his first professional tour, he began a high-profile series of matches with Karel Koželuh, who consistently outplayed him on clay courts. Richards would have to settle for triumphs on grass, meeting the Czech at the US Pro finals in 1928, 1929, and 1930, and winning two of the three.

Then in 1931, Tilden turned pro, and Vinnie was back to challenger status on fast courts as well. Veteran journalist Ned Potter wrote of Richards before the 1924 nationals, “The master was no longer a hero to his valet.” Maybe, but between 1931 and 1946, the master–despite a ten-year disadvantage in age–won 54 of their 59 recorded pro meetings.

Richards had to settle for fame and modest fortune. He never lost his desire to compete, entering pro events into his 40s, even after his expanding waistline slowed him down. He once tried to quantify his own career: “I figure I played about 14,000 matches, and in each one I ran about four and a half miles. That means I ran 56,000 miles or about twice around the world.” His assumptions were questionable, but the spirit was sound. No matter what obstacles the USLTA threw in his path, the man played a lot of great tennis.