Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

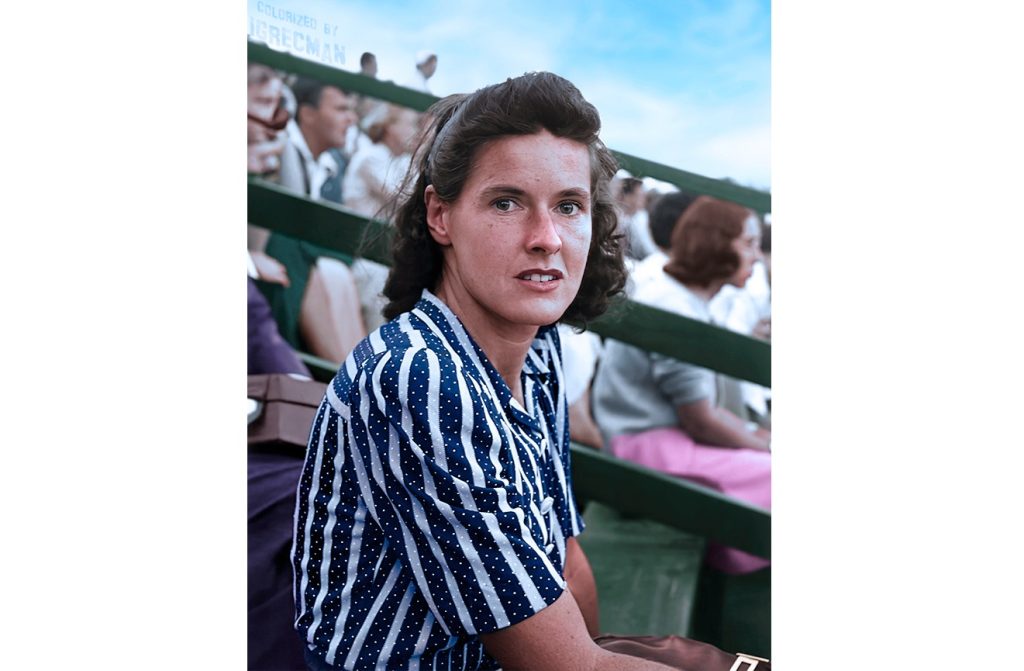

Sarah Palfrey Cooke [USA]Born: 18 September 1912

Died: 27 February 1996

Career: 1926-47

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 4 (in 1934, and US #1 in 1945, when no world rankings were published)

Peak Elo rating: 2,273 (1st place, 1941)

Major singles titles: 2

Total singles titles: 33

* * *

Sarah Palfrey Cooke was, in the parlance of her time, “much married.” In 1934, when she was 22, she wed upper-crust Bostonian Marshal Fabyan. They split five years later, and in 1940 she married Elwood Cooke, a fellow tennis player who had lost to Bobby Riggs in the Wimbledon final the year before. The second marriage lasted until 1949, and a couple years after that, Sarah went to the altar one last time, with television producer Jerome Alan Danzig.

I bring this up partly to hint at the difficulty of keeping track of players in the amateur era. Newspapers were scrupulous about using married names, so with variations such as “Mrs. Cooke,” and “Sarah Palfrey Fabyan,” Sarah was referred to by at least a half-dozen different monikers. Her most memorable feats on court–the US national titles in 1941 and 1945–came during her second marriage, so tennis history has enshrined her as Sarah Palfrey Cooke.

Elwood’s influence, however, goes far beyond the name. When the couple got together, Sarah was also known by a less-flattering tag: Little Miss Almost. When she won the national junior tournament in 1928, experts viewed her as three years away from annexing the adult championship as well. Yet by 1940, she had entered America’s premier event every year, and she had nothing to show for it besides a couple of straight-set losses to Helen Jacobs in the 1934 and 1935 finals.

Jacobs profiled Palfrey in her 1949 book, Gallery of Champions. Jacobs was as accomplished and independent a woman as you’ll find in the sport’s history, and she was rarely one to attribute a wife’s success to her husband. But in Sarah’s case, she recognized Elwood’s “calm match play spirit” and explained the development that turned Little Miss Almost into a two-time titlist:

Elwood Cooke … worked assiduously with her to develop in her game stylish, effortless stroking similar to his own. Though there appeared to be little room for improvement in the production of Sarah’s strokes, her forehand and service were handicapped by an unorthodox wrist action that robbed them of much pace. This was eradicated and made, I think, the difference between the near-champion and champion.

With another strong tennis mind in her corner, Sarah won the national title in 1941, on her 14th attempt.

* * *

From our perspective 80 years on, the “Little Miss Almost” label is a bit of a puzzler. In Palfrey Cooke’s first 13 tries at Forest Hills, she reached only those two finals against Jacobs, winning five games in 1934 and six in 1935. No spectator walked away from either of those matches thinking that Sarah almost won the title.

From 1928, when she first entered the US championships, to 1937, her other results were equally uninspiring. She lost in her first match on four occasions, three of them when she was a top-five seed. The fact that all four of them went to three sets is little consolation. Jacobs explained what was missing from Palfrey Cooke’s mindset:

Sarah had still to learn that she could spare herself a lot of trouble if she would begin a match with the concentration, resourcefulness and determination that she applied when she found herself in an apparently hopeless position. Too often, she made the task of winning just as difficult for herself as possible by her delayed reaction to the problems of a match.

Case in point: She lost to Dorothy Andrus–a solid but unthreatening veteran who won 14 matches in her 12 entries at the national tournament–in the 1937 first round. Sarah, the third seed that year, was ousted 12-10, 0-6, 7-5.

The “almost” of her nickname rests almost entirely on the 1938 semi-final she played against Alice Marble. Marble was the second seed that year, and Sarah was fourth. After Jacobs, the Wimbledon champion, lost in the round of 16, whoever emerged from the Marble-Palfrey half would be the favorite to win the title. The match would be a nervy one, and it didn’t help that the players had to wait six days for the rain to pass and the turf to dry before they could finally take the court.

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

Allison Danzig wrote in the New York Times that Sarah “played a beautiful, heady match … only to lose under heart-breaking circumstances.” Somehow, that was an understatement. After a rocky start that allowed Marble to build a 5-1 lead in the first set, “Mrs. Fabyan”–as the Times called her–took a more aggressive tack, and reeled off nine games in a row. That gave her the first set and a head start on the second.

Alice had won five titles that year and lost only a single match, so it was only a matter of time before the momentum shifted again. From near-disaster, with Sarah a point away from a 4-0 advantage in the second, Marble “played as brilliant tennis as she ever has shown at Forest Hills.” Danzig wrote, “Mrs. Fabyan, a valiant retriever and defender throughout, seldom yielded a point without a struggle, but Miss Marble was playing tennis that was simply invincible in its power and control.”

Still, Sarah reached 5-2 in the second set, and held two match points when Marble served at 15-40. But Marble salvaged a hold and didn’t lose another game until the third set. The decider went to Alice by the same score, giving her a 5-7, 7-5, 7-5 victory.

In the final the next day, Marble beat Nancy Wynne, 6-0, 6-3. In retrospect, Sarah’s missed opportunities in the second set of the semi-final weren’t just match points, they were championship points.

* * *

There was nothing “almost” about Sarah Palfrey Cooke on the doubles court. She won her first national title before her 18th birthday, partnering Betty Nuthall to win the US Nationals in 1930. She would ultimately win 11 women’s doubles majors, including three with Helen Jacobs and six with Alice Marble. (One of them was played just a few weeks before their dramatic 1938 semi-final.) She tacked on five more mixed titles with five different partners, including Don Budge and, in 1939, her future husband Elwood.

Jacobs was an excellent doubles player, but she considered Sarah the better half of their team: “There was no question but that my partner was the leading doubles player in the United States. Her forecourt game was equal to any one of the greatest, including Elizabeth Ryan’s.” Pauline Betz, who would play 15 singles finals against Sarah between 1940 and 1945, found her “[hard] to pass … as her anticipation is such that she is usually waiting at the right spot.”

Palfrey and Jacobs made for a daunting duo, but Sarah’s most impressive feats would come alongside Marble. Decades later, she wrote, “Our games and temperaments were completely in sync.” Sarah could hardly have picked a better partner. Alice won more than 100 consecutive singles matches starting after her semi-final loss at Wimbledon in 1938. The pair was equally unbeatable in doubles competition, running off a three-year-long win streak that ended only when Marble turned pro in 1940.

Lest anyone think that Marble carried her partner all those years, Sarah won both national doubles titles in 1941. She took the women’s crown with Margaret Osborne (later duPont), and won her fourth national mixed championship, this one with the 20-year-old Jack Kramer.

* * *

Her most unique doubles feat was still to come. After her “triple” at the 1941 US championships, tennis took second place to motherhood, and she stayed home while Elwood served in the navy. She made a brief comeback to play at Forest Hills in 1943, but she lost in the quarter-finals to Doris Hart and would remain semi-retired until 1945.

In the last year of World War II, Elwood was discharged from his military duties, and Sarah was ready to take on a full season of tennis. With a two-year-old daughter in tow, she was nearly as successful as she had been in her belated breakthrough year of 1941. She spent the first half of the season in California, where she won two singles titles and beat everyone she played except for the woman who dominated Forest Hills in her absence, Pauline Betz. On three separate occasions, she pushed Betz–the best player in the world at the time–to three sets.

The first stop on the family’s summer tour was the Tri-State Championships in Cincinnati. Many players were still fulfilling their military duties, so the men’s field was lighter than usual and quality doubles partners were at a premium. That gave Elwood the excuse he needed to team up with one of the best players in the world. There was no mixed event in Cincinnati, so Mr. and Mrs. Cooke entered the men’s doubles.

The amateur era had its share of oddities, and the war forced people to make do. But tennis still clung to its traditions–a mixed-gender team in a men’s doubles draw in 1945 was weird. The Tri-State was an established feature on the tennis calendar, and it drew strong fields, if not as world-class as the Cincinnati event does today. Very occasionally, a woman would play doubles with three men in an exhibition, but never–as far as I know–in high-level tournament play.

The Cincinnati Enquirer confirmed that everything was above-board: “[A] check of the rule book convinced officials that there is nothing to prevent the pairing of a man and woman if no objection is raised by other contestants.” Apparently no one complained, though within a few days, several men may have wished they had spoken up.

Sarah Palfrey Cooke more than held her own. She and Elwood cruised past three local teams to reach the final four, losing only six games in six sets. Their first real test came in the semis, against a pair of established circuit players, Buddy Behrens and Tom Molloy. The Cookes squeaked through, 6-3, 5-7, 10-8, while Sarah–partnering Dorothy Bundy–also reached the women’s doubles final.

Alas, the Cookes would make history only as the runner-up. Their opponents in the men’s doubles final were top seeds Billy Talbert and Hal Surface. Talbert was the strongest player in the field, having reached the national singles final the year before. An hour after Sarah took the women’s doubles crown over Mary Arnold and Shirley Fry, she and Elwood fell, 6-2, 6-2, to Talbert and Surface.

News coverage of the tournament was surprisingly unconcerned with the out-of-place mixed doubles team. After the marathon semi-final, the Enquirer allowed that “Mrs. Cooke is one of the best doubles players of either sex in the nation.” Two days later, the paper hinted at the gender gap, saying that in the final, the Cookes “could not quite cope with the greater speed and court covering ability of the two men.” The Associated Press report said only that “the unusual husband-wife duo … failed to click.”

The rare loss hardly derailed Sarah’s season. In singles, she went 33-3 the rest of the way, losing only to Betz, Doris Hart, Margaret Osborne–all in three sets. She capped the 1945 campaign with a nine-match winning streak and her second national title, toppling Betz in a hard-fought final.

* * *

Sarah’s second triumph at Forest Hills was the end of her amateur career. Now 33 years old, she left the circuit behind in favor of opportunities in radio and marketing, not to mention her young daughter. Yet she hardly fell into obscurity.

In early 1947, Elwood sent out feelers to tennis clubs around the world to gauge interest for a professional tour featuring his wife and Pauline Betz. Sarah had moved on–she did the color commentary for 1946-47 New York Knicks radio broadcasts, a rare example of a woman in such a role at the time–but Betz remained queen of the courts, holding both the 1946 Wimbledon and US titles.

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

The governing body of US amateur tennis, the USLTA, got wind of the plan in April. Not a date had been booked; not a dollar had changed hands. But the mere whiff of professionalism provoked an overreaction, and Betz lost her amateur status. (Sarah did too, but it didn’t matter to someone who was effectively retired.) The two women went ahead with a barnstorming tour that took them through dozens of cities and several countries before the end of the year. Unfortunately, women’s professional tennis wouldn’t catch on until the Open Era, despite occasional attempts–often involving Betz–to make the pro game a two-gender concern.

Just as Sarah was content to lose her amateur status, she was fine to miss out on a long professional career. Elwood would play pro tournaments through the end of the decade, but the couple split. She next turned up on the tennis scene in 1950, when she and Alice Marble lobbied the USLTA to drop its color bar and allow Althea Gibson to compete. Sarah escorted Gibson on her first visit to Forest Hills and warmed her up before her debut match.

Like Sarah Palfrey Cooke before her, Althea Gibson wasn’t an immediate success at the national championships. She lost in the 1950 second round to Louise Brough, and she wouldn’t make it past the quarter-finals until 1956. She even lost to some of the same players who had stopped Sarah a decade earlier, falling to Doris Hart in 1952 and Shirley Fry in 1956.

The upper-class Bostonian and the pathbreaking Black player didn’t have much in common, but both women persisted through their early struggles to win multiple national championships. Sarah relegated the “almost” nickname to a curiosity in her biography, and Althea–thanks in some small part to the establishment figures who fought for her–ensured that no one would ever have reason to use the word to describe her.